“A painter paints pictures on canvas. But musicians paint their pictures on silence.”

Leopold Stokowski, Conductor

The Chicken or the Egg

As a writer of fiction and the husband of a classical musician, one unanswerable yet persistent philosophical question has recently consumed my mind.

Which came first — story or music?

Similar to the chicken-and-egg conundrum, it seems to me that storytelling would naturally inspire music, but so, too, would music naturally provoke story. Neither could have existed for long without evolving into the other. These two art forms go hand in hand, and both seem as ineffably intrinsic to the human experience as the biological functioning of our heartbeats. Did they develop simultaneously? Or is one the sire and the other the heir?

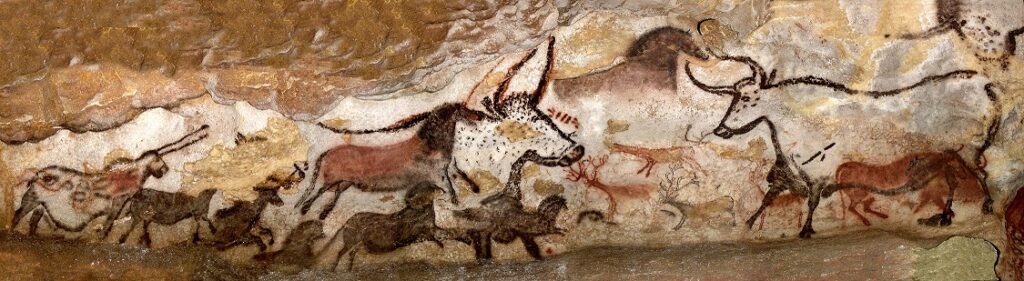

Both narrative and music also share another common element: every single time we find the “earliest” indication of storytelling or a practice of music in so-called “primitive” cultures, it is only a matter of time before we archaeologically discover something earlier,[1] perhaps from a different geographically unrelated people,[2] that shows that these arts have longer histories than we could ever have imagined.[3] In the final analysis, I believe we will never discover the origins of story and music, as they will both be lost to the unreliable politics and pitfalls of time, recorded history, and memory. To me, this does not feel sad; it feels apropos. I myself do not remember the day I discovered story or music within me; one day, they were simply there, well before my memory even began, albeit primitive in form and/or specificity. Why should it be any different for the experience of the entire species? Does it not feel more right to know that these beautiful expressions so natural to human behavior began far before our collective cultural memories even began, that perhaps we had them long before we were even human in the way that we believe ourselves to be now?

For a full virtual experience of the Lascaux Cave paintings, please click here.

And yet music and story, like the stars above, are far too integral to our collective interest to keep us from wondering ineluctably about their nature, source, and history. We must look; we must question; we must speculate.

Another similarity: the creation of story and of music are possible with no other tools than our own bodies. All that story and song require is voice, a tool which leaves no specific archaeological trace. While these expressions are fundamentally and inherently accessible, their origins are equally fundamentally and inherently elusive.

And yet, as a lover of myth and folklore, I can’t help but notice one fundamental difference between music and story.

There are countless ancient cultural myths, legends, and stories about the origins of music; yet there are very few tales remembered or relayed today about the origins of story.[4] (My research into music has been less thorough, so take the following with the proverbial grain of salt, but I have also never heard of a classical music piece composed about story origin, though I know of several dealing with music origin legends, especially from Greek mythology, such as Pan-Syrinx, Orpheus-Eurydice, the muses, or the music of the spheres; please feel free to correct me in the comments if I have committed an oversight in these statements.) Perhaps that form of meta-oratory — creating a story about where stories themselves came from — has been logically or intuitively problematic. Or perhaps we choose to more frequently celebrate the birth of music because it is the side of the coin that is produced and absorbed on a more sensorily dizzying participatory level. When we listen to a storyteller around a campfire, our instinct is to be silent and rapt with attention, as still as a tensed muscle, lost in the voice, the language, the characters, and the world. We want to feel ephemeral and evanescent, as if we exist only as an insubstantial voyeur into the worlds being created. When we listen to a musician, on the other hand, our instinct is to participate, to sing along, to clap our hands or stamp our feet, to join in and jam. We want the tactile experience of the ground under our feet, the instrument in our hands, the song from our throats.

Attentive silence, though of course not exclusively, seems to be a natural audience experience of story. Rapturous noise, though of course not exclusively, is the natural audience experience of music.

Perhaps storytelling is more like magical performance, where we seek not to look behind the curtain and instead prefer the “reality” inculcated by the suspension of disbelief, where we choose more exclusively to be either artist or audience — and music is more like an open mic night, where we seek more naturally to be both artist and audience, where it hurts to just watch and is joyous to join in.

Which came first — the story or the music? Which came first — our instinct to be still and listen in awe, or our desire to play along?

It’s a fun philosophical debate to be had, and certainly there is merit to both sides of the argument, but I also find increasingly that within the interrelationship between story and music lie clues into the very future of classical music. The history of music has always been intertwined with story, and I believe the modern musician must understand music and story’s historically evolving interrelationship in order to tap into the contemporary zeitgeist and actually fill and connect with an audience. Perhaps in asking unanswerable questions, such as “which of the art forms of story and music came first?”, we will come to a deeper understanding of how and why they work together, and how and when they will not. Near the end of this article, I will also provide an example of a classical music show on which I served as creative director, to illustrate the lessons I have taken from these lines of thought.

But first — I have selected and retold three myths regarding the origin of music that I believe to be largely unfamiliar in the Western world and that shed light in different ways on the nature of this relationship between story and music. In looking forward, I seek to look back, to some of the very first tales that human beings across this globe told about music’s source and nature. As a writer of fiction, I believe wholeheartedly that there is nothing like folklore to elucidate our deepest and most fundamentally human values, attitudes, expectations, and opinions.

So here we go, dear listener. Settle in around the campfire, get warm and comfortable, perhaps have some wine to lubricate your blood. I ask for your silent attention for some time, so that you may hear three ancient tales from around this earth about how music first came to a humanity so grievously deprived.

Finland: Väinämöinen and The Pike

(Retold from the epic Finnish poem Kalevela)

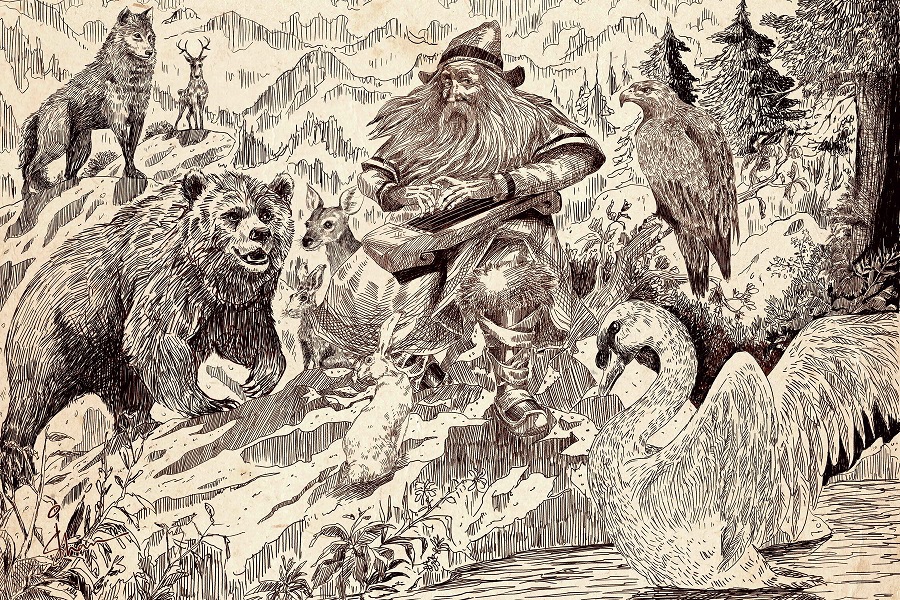

Väinämöinen, the demigod with the magical voice, stood on the prow of the ship, looking across at the stormy seas. Accompanying him were the master blacksmith Ilmarinen and the great hero Lemminkäinen, who, alongside their shipmen, worked the sails, the thick knotted ropes cutting into their calloused palms. But Väinämöinen’s thoughts were far too occupied to much notice their exertions.

For aeons, since the beginning of time and his own storied birth to the goddess Ilmatar, Väinämöinen had fought for the people of Kalevela against the witches of the far northern city of Pohjola. And now Pohjola had struck again and stolen the great Sampo, an artifact forged by Ilmarinen to bring wealth to whomever possessed it. For years, the Sampo had brought prosperity to Kalevela, but now it sat in the throne room of the witch Louhi, the mistress of Pohjola. And so, aged Väinämöinen was again headed into battle.

Väinämöinen was so consumed by thoughts of impending war that he was almost thrown off his feet when the ship lurched to an unexpected stop, striking ground on something solid.

Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen dangled their oars overboard, finding purchase against whatever was below, but still unable, even with all their strength, to free the ship.

“See what it is we’re stuck on!” thundered Väinämöinen. “A sand shoal! A rock! A giant tree!”

It was Lemminkäinen, always reckless and impulsive to act, who dangled himself off the mast to look below the boat. He soon resurfaced, astonished. “It is none of those things! It is a giant pike, a fish unlike anything I have ever seen! We sit upon its back!”

Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen dived into the water and stabbed at the pike, attempting to slice it, but their blades could not cut through the beast’s thick scales. They reclimbed the ship and turned helplessly to Väinämöinen.

Väinämöinen, weary but determined, began to sing, and with his magical voice, formed a great sword from the water itself, sharper than any blade crafted by human hands. He dove into the water and sliced that fearsome pike in half.

That night, on a deserted island, the three adventurers and their crew enjoyed a grand fish dinner. Väinämöinen watched the pike’s giant jawbone roasting upon the spit. He turned to Ilmarinen. “That is a great jawbone,” said the old man to the blacksmith. “I believe a true craftsman can create something truly unique from it.”

Ilmarinen, normally not one to shrink from a challenge, looked at the jawbone and scoffed. “Not even a true craftsman can make anything of note from that.”

Later that night, when all the others were asleep, Väinämöinen took the jawbone and himself became a craftsman. He fashioned it into a harp: the jawbone became the frame; the teeth became the pegs; and the hair of a gelding became the strings. He held up this harp — the first instrument ever created — and named it kantele.

Lemminkäinen saw the harp, mused that it was beautiful, and attempted to play it. No sound arose. An elderly shipman tried to play it next. He too failed. “We might as well throw it into the water,” he said, as all the crew murmured assent behind him.

And then words arose from the instrument itself: “I will not go under the waves! I will resound only in the hands of the one who took the trouble to make me.”

The astonished shipmen handed the kantele back to Väinämöinen. And as the sun rose, he began to play, his fingers racing across the strings. The music that was made was stunning and resonant and beautiful, a sound without equal. Rapture followed rapture; joy followed joy. All the animals of the island — from squirrels to weasels, elk to lynxes, wolves to bears — raced forward, leapt in exultation, flew in circles, and danced to the music.

Deities themselves appeared in the sky above the clouds, nodding their heads in approval and listening with rapture. As the Kalevela itself states of the deities, “some were radiant on the shaft-bow of the sky, on the rainbow, others were magnificent on the rosy-edged tip of a little cloud…”

Old Väinämöinen played for a day or for a second. However long, it was enough for the whole world, without exception, to rejoice. When he was done, Väinämöinen began to weep, and his tears formed beautiful blue pearls in the ocean. In a little while, he and his men would reboard their ships and continue on into battle. But for now, Väinämöinen held the kantele and wept.

And so it was, in Finnish mythistory, that the demigod Väinämöinen invented music from the jawbone of a giant fish.

China: Fuxi and the Parasol Tree

(Retold from Shen Yun tradition)

This is a tale from the very dawn of humanity, when immortals and mortals shared the world as one.

The demigod Fuxi — who had been appointed by his father, the great God of Thunder, to be the Celestial Ruler of the East and watch and protect the happenings of the human world — went for a walk in the mortal world. He was filled with consternation. He had given the humans so much, filling all their needs that he could see, and yet… they were still lacking some fundamental joy.

Fuxi had the head of a human and the body of a dragon. As he walked, he looked down at the clawed footprints he left in the mud, considering all that had led him to this moment. His mother was a human who, as a young woman, had become mysteriously pregnant after accidentally treading in the footprint of a giant. As a result, Fuxi was born, and though many were horrified to see him, his mother never abandoned him. Even as he grew and grew, she stood by his side and loved him. It was not until he was fully grown, towering over the town itself, that he went in search of his father.

Once appointed to be the Celestial Ruler of the East, Fuxi had done well by his human subjects. When he saw that they were hungry, he invented fishnets and weapons with which they could hunt. When he saw that they fell ill from eating raw meat, he taught them how to make fire. When he saw that they were lonely, he invented marriage to bond couples in matrimony. When he saw that they were aimless, he invented divination so that they could tell stories about their futures, finding purpose and direction in their lives.

Each step had brought them closer to joy, but still, something was missing. And it was at this point that Fuxi came across a stunningly beautiful parasol tree.

As he moved closer to the tree, studying it, the sun suddenly sent forth twilight rays — though it was midday — and painted the skies in a stunning red. The planets above showered cosmic elixir on the tree’s branches. A heavenly chime sounded, and the tree gave forth a fragrant breeze. A single cloud descended upon the tree, and a pair of phoenixes burst out. Joined at once by countless birds, they opened their beaks and began to sing.

Fuxi was struck by inspiration. This was a special tree, and surely any tool created from its wood could not fail to be wondrous.

He cut down a branch and started building. This new tool tapered to one end at four inches across, representing the four seasons. Its two-inch thickness on the other end corresponded to the dual forces of yin and yang. Across its top, Fuxi fixed twelve frets for each month of the year, and then connected five strings for the Five Elements. What he built most closely resembles what today we would call a zither.

Fuxi carried the new instrument, which the gods themselves would eventually name yaoqin (precious jade), to the humans. At the humans’ feast each year, it was custom for him to present them with a new gift. So, Fuxi watched as they ate their fill from the prosperous hunt and heard prophecies of their future, patiently awaiting to see what his next gift would be. Then it was time.

Fuxi began to play his yaoqin…

They sang in response. And they danced in response. And a young man took the yaoqin from Fuxi and tried to play it himself. Fuxi guided him gently and, with great joy, the man played the precious instrument. For every feast and for every generation across millennia, this gift would reverberate across the mortal lands and echo even into the heavens.

And so it was, in Shen Yun mythistory, that the demigod Fuxi invented music from the branch of a parasol tree.

India: The Musician and the Monkey

(Retold from Hindustani tradition)

Narada Muni played his veena, a large harp draped across his lap, before a rapt audience in the court of Lord Krishna. The audience’s eyes were closed, and as they listened to him play, they were all filled with the love of the divine. As Narada played, he thought of the unusual gift he had been decreed.

It was Brahma Himself, the Creator of all things, that had written the Samveda, the Veda of Music, as a balm for a world of humans lost increasingly to lust, hatred, and immorality. In His great wisdom, He had given this Veda to Lord Shiva, who in turn passed it on to Goddess Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge. Saraswati was given the task of finding an eminent soul to become the First Musician and to teach music to all those who were worthy. After surveying all of the possible recipients, She chose Narada Muni, the sage who had lived and wandered for thousands of years through all three lokas (the bhuvarloka of heaven, bhuloka of earth, and atalaloka of the underworld). Since the bestowal of Saraswati’s gift, for aeons now, Narada wandered the world with his khartal (hand-clapper) and veena, teaching music to Gandharvas (half-humans, half-gods), kinnaras (half-humans, half-birds), and apsaras (spirit dancers of cloud and wind). He had ensured that only celestial beings who had what he considered a true appreciation of the divine would be taught these great musical techniques, for it was a celestial gift that should never be squandered on the lowly.[5]

As Narada struck the last note, he thought of the Goddess Saraswati and filled his heart with Her. The last note reverberated in the marble chamber, and it was several moments before all of the assembled people opened their eyes. There was a stunned silence that seemed to echo as loudly as the music itself. Smiling, Narada turned to Krishna to receive appreciation.

Krishna’s face, however, was blank. Instead, he leaned onto his left elbow on his mighty throne, and revealed a monkey seated on the back of his chair, over his right shoulder. The monkey’s eyes were closed, still lost in the music. Narada was stunned. A monkey, seated in such a place of honor? Krishna had always been playful, but this was unthinkable. Finally, the monkey reopened its eyes.

Krishna asked the monkey, “What did you think?”

Narada’s face went ashen. Though the monkey answered, Narada did not hear the words. What right did a monkey have to judge his music? What could such a lower being know about the Samveda, about the veena, about true devotion to the gods?

“I see the consternation writ across your face,” Krishna said to the sage, smiling. “Perhaps you are right. Perhaps a monkey is not qualified to judge you. Let us see. Hand me your veena.”

Narada’s fingers curled protectively around his instrument. The bond between musician and instrument is sacred. Saraswati Herself had said so. But he could not deny the request of an incarnation of Vishnu Himself. Trembling with frustration, Narada handed his veena over to Krishna.

Krishna, amused, handed it at once to the monkey. “Play the veena and let us see what you know,” he said.

Narada’s heart froze at the sight of the creature handling his veena. He sat in place, stifling his temper as the monkey inexpertly laid the veena on its lap, and began plucking at the strings with hairy fingers. The notes were only half-resonant, and the order in which the monkey played them was nonsensical and impulsive. And yet, when the monkey opened its mouth and began to sing, it sang in devotion to Lord Rama. Despite the unpolished nature of the performance, Narada was stunned to see that the court stood in rapt attention and awe of this song as well, clearly feeling the true and heart-felt devotion behind each word. In fact, within a few moments, a number of faces seemed even more engaged by the monkey’s performance than by his own. They were weeping. They were singing along. They were swaying. They were moved.

Once the monkey had completed its song, the gathered court burst into resounding applause. The monkey handed the veena back to Narada, and the sage turned to face Krishna.

“I understand the lesson you wish to teach me,” said Narada to Krishna, “for this can be no ordinary monkey. This must be Hanuman, first devotee of Lord Rama. How else could he sing with such bhakti for Lord Rama?”

“You are correct,” the monkey said. “I am Hanuman. But I am also an ordinary monkey.”

Krishna said to Narada, “Goddess Saraswati told you that music must only be given to the worthy, those that have a true devotion to the divine. This is true. But never forget, Narada Muni, that worthiness can be found in all places — and music cannot be a balm for the world if it is never heard by those who have lost their way the most.”

Narada left Krishna’s court completely changed. He began to teach the secrets of Hindustani music to those ordinary humans he found worthy, and they in turn played frequently for human audiences. Evil is never fully lost from the earth, but these songs of devotion helped humanity to stand a chance of resisting the darkest temptations of their souls.

Ultimately, to help humans achieve worthiness even more quickly, Narada Muni even encouraged sage Vyasa (known for translating the Puranas of the Gods in a way that humans could understand) to write the epic story of the Mahabharata, so that humanity could come to true devotion and worth more quickly. Narada realized, that day in Krishna’s court, that music was meant to be performed with devotion by those who were worthy to those who need only listen with open hearts.

And so it was, in Hindustani mythistory, that the sage Narada Muni brought music to humanity, chastened by the song of a monkey.

Richard Wagner and Gesamtkunstwerk

The above three myths exist among countless others from around the world. I could also have told you the Nahua Aztec myth of Quetzacoatl stealing music from the Kingdom of the Sun, the Persian legend of King Jamshid as the inventor of music, the Mughal story of Tansen in the court of Akbar able to bring fire and rain with his choice of raag, the Native American Dakota tale of the first flute, or the frightening Greek tales of Pan and Syrinx or of Hermes and his tortoise-made lyre. But I chose the above three because they are lesser known in the popular Western sphere, seemed directly impactful to my queries, and shared stunning similarities. In all three tales, the first instrument is a form of harp, the purveyor of music to humanity is either half-human or at least more than mortal, and the Gods are either directly responsible for the music or approve of its invention whole-heartedly.

On the other hand, when it comes to the question of which came first, story or music, these three myths all offer different answers. In the Finnish Kalevela, there is no mention of the origin of story and whether it predated Väinämöinen’s invention of music. In the Shen Yun story, it is directly stated that story came first in the form of divination, but still the world was without joy — until the invention of music by the demigod Fuxi. And in the Hindustani story, it is music that comes first, after which epic storytelling is created to increase the human devotion to God necessary to become worthy of music. Each of these myths answers that original conundrum differently. Furthermore, one thing stuck out to me in great force.

In none of these origin myths do humans respond to the creation of music and instruments by sitting still. The audience responds to these early songs with unabashed joy and movement and participation; they wish to move towards the source of the sound, to play along, or to sing and dance. Lemminkäinen’s first instinct is to try to play the kantele. Fuxi’s listeners dance and sing and ask to learn the yaoqin. And when the audience is still and silent when Narada plays his veena, they are appreciative but not as noticeably moved as when the monkey plays. To consider one more myth, take the famous Greek tale of the siren song: knowing that men are driven to shipwreck their boats in desperate attempt to advance toward the music of the sirens, Odysseus must forcibly lash himself to his mainmast to avoid the temptation. The music literally drives people to approach — to move.

In these origin myths, humanity’s deepest response to music is not stillness or silence, but movement and noise. Music is not intended to be quietly listened to. Concrete separation between artist and audience — between the makers of noise and its silent recipients — is not what makes music joyous.

Many classical music scholars agree:[6] the history of music can be divided into two eras — pre-Wagner and post-Wagner. Regardless of one’s feelings about Wagner’s person or politics, it is unquestionable that Wagner changed the way classical music was absorbed. He was the one who built his opera house in aisles, so that audience members would feel locked in and unable to freely move about, therefore more absorbed in the performance. He was the one who staggered the seating, so that donors would have the best view, provoking people to look at classical music as the more rightful property of the elite. He was the one who introduced blackouts to the stage, to force people to listen (with rapt attention) in darkness, without distraction from those around them. He was the one who placed his orchestra invisibly into the pit, so they could be heard but not interacted with. And he was the one who decided that music performance was incomplete without story, building his ideals of gesamtkunstwerk (universal artwork) into performance, melding story and music inextricably. Of course this is not to say Wagner is single-handedly responsible for classical music’s audience expectations of sitting in silence, just that his overwhelming success as a composer was instrumental in formalizing the rigidity of the classical music experience.

Wagner’s ideas make sense for opera; as stated above, sitting still in silence is a sound (no pun intended) response to storytelling, but for music alone, it is practically unnatural. Why should Wagner’s ideas of gesamtkunstwerk and his expectations of audience behavior filter into non-narrative experiences of classical music? Why do we sit still in bolted seating for pieces meant to be absorbed solely as music, not as opera or in combination with theatrical narrative? Consider that at any rock music venue, the more expensive tickets are the ones where you stand closer to the stage, able to dance and interact with those around you, rather than sit far away. In this way, audiences of classical music have lost several phenomenological advantages that would help them truly move, dance, interact with, and enjoy the music. While pop music fills stadiums, classical music struggles to maintain an audience. Its demographics skew older and wealthier. Could learned behavioral expectations be the reasons why? I understand that breaking free from these traditions can be frustrating for the modern classical musician, trained to exit and re-enter the stage between works by different composers or to expect silence even between movements, but I contend that classical music has no choice but to evolve its central rituals, or else admit to being the music of a niche exclusive elite.

Imagine going to a pop concert and being expected to sit still and listen quietly, or not applaud when you felt like it, or only ever see your favorite artists on stage in a formal concert black. Classical musicians remind people frequently that classical music was the pop music of its time, but they frequently also preclude the presentational aspects of pop music, reducing the spectacle and maximizing the pomp. Small wonder then that presentationally, classical music is seen as didactic, inaccessible, and, for general audiences, even joyless.

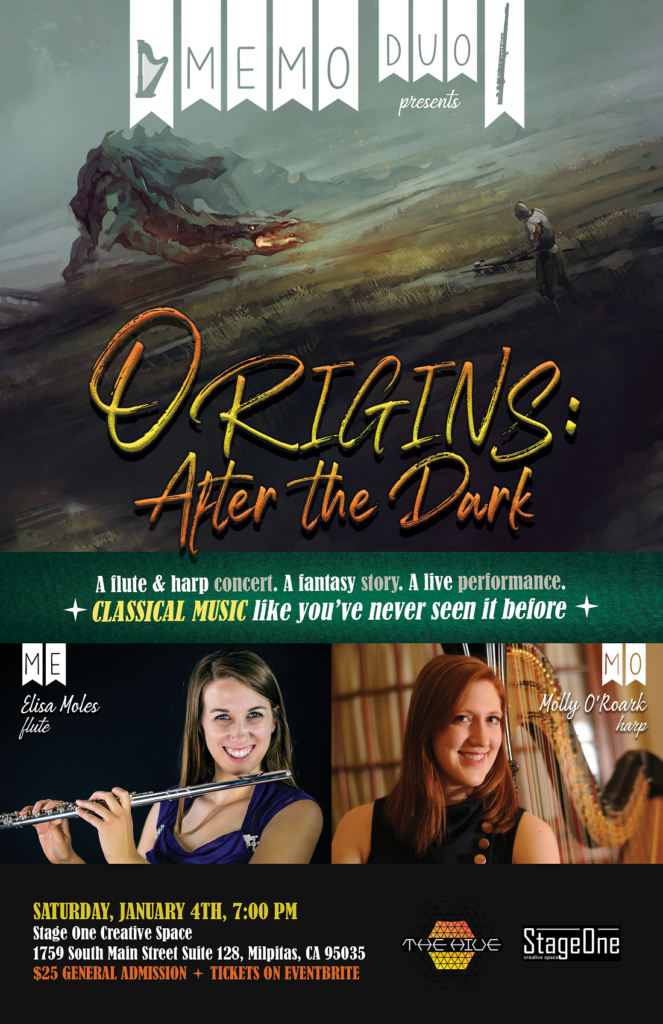

Origins: After the Dark

I saw first-hand the potential of classical music to connect more fully with a modern audience in early January of 2020. Just before the pandemic upended “normal” life, my flutist wife Elisa Moles and her harp partner Molly O’Roark (members of the chamber group MEMO duo), played a show called Origins: After the Dark in San Jose, California. Their program of classical repertoire included such beautiful and passionate pieces as Charles Rochester Young’s Song of the Lark, Andy Scott’s Sonata for Flute and Harp, and Ravi Shankar’s L’Aube Enchantée Sur Le Raga Todi. But how, we asked ourselves, could we eschew outdated and joyless practices while still presenting the material in a way that would be accessible to a modern audience?

Given my background writing and directing film and theater, I joined the project as creative director. I wrote a brand-new original myth about the origin of music. Elisa and Molly’s musical performances were punctuated by a theatrical version of this tale, and they themselves performed as sister witch characters on-stage. We cast the other roles with actors from stage and screen. We decided to stage the show in an unusual classical music setting: a film studio where commercials and TV shows were shot and where the audience would be seated on folding chairs — no staggered seating. We had a stunt choreographer plan out the fight scenes (to be scored with live music performed by Elisa and Molly). We had a special effects make-up artist turn an actor into a monster. I planned out lighting grid and color washes on the back Cyclorama with a lighting operator. And I designed projections — still and video — that could be shown behind our performers to stage sets and provide mood for the pieces. We built and constructed a cardboard set that could hide a stunt crash-pad when our actors went flying backwards. And we purchased medieval costumes and props to help tell the story. It was by no means high-budget, but we utilized all resources at our disposal to make it a full production.

The story of the show was deeply personal to me as an artist. It was about a young man named Amar who heard a song in the wind — the song had been there all along for all of time but, because it had always been present, everyone had lost the ability to hear it. For some reason, one day, Amar awoke to it, and like the beautiful siren song, it lured him through great danger to its source. There, at a lake, he discovered that the song was made by huge beasts that were mostly jaws and teeth: the monstrous amphibious Moga (a Sanskrit word that means obsession). The Moga were guarded by knights who stood watch around the water so that they could not escape and consume the world. Amar at first could not fathom that such beauty could be created by obsessive ferocious monsters; ultimately, however, he comes to understand that in order for the songs to be created, artistry must be the result of the balance between both the obsessive monster and the steadfast knight, and that any artist is incomplete without a grounding influence.

That, to me, is the relationship between story and song — each one standing as faithful knight to keep in balance the obsessions of the other.

This, my own myth about the origin of music, was a deeply personal story. It was our version of gesamtkunstwerk, a classical music show intersected with a full theatrical play that brought a narrative shape and arc to the selected pieces. But unlike Wagner, we encouraged applause whenever and wherever. Molly and Elisa performed not in a pit below the play, but on-stage with the actors, sometimes so close to the stunt fighting that I cringed in fear, backstage behind the projection computer, for the safety of Molly’s harp. At one point during the performance, I went to the green room to give a final note to one of the actors, and found several of them dancing energetically and joyously to the Andy Scott movement that Elisa and Molly were playing onstage. We abandoned the rituals, we embraced storytelling and spectacle, and we had no expectation of silence. The result was an indelible excitement from the sold-out audience. We heard from many people who had not previously enjoyed classical music that they had found an inroad to understanding and loving it. Yes, there were those, especially those who were used to more traditional classical music recitals and shows, who felt a little overwhelmed by it all. But for us, we left on personal career highs, excited to see what we could do next, and energized by the potentials of this format and formula.

Mythology as the Key to the Universal Human Heart

Which came first — the story or the music?

It’s an unanswerable question, but most importantly, the reason this query is without response is because they are as tied to each other — each one as much an heir of the other — as a chicken and an egg. The caveat is, of course, the more we marry the two, provided we are successful in our craft, the more we can expect both audience reactions of rapt attention and rapturous movement. We must perform in spaces where audiences are encouraged and able to do both. Our ancestors’ mythologies understand this fundamental truth: narrative and music are inextricably intertwined, both helixes of a DNA strand, both sides of the same coin, both swirling around each other at all times. The more we can project the story within the music and the music within the story, and the fewer rigid stipulations there are about how an audience expresses the joy that they feel when they hear music, the more we can connect with a listener’s natural and fundamental impulses, instincts, and reactions. Myths are an essential tool to understanding humanity’s universal beating heart; we must strive to interpret their lessons if we desire to connect to and move an audience.

This is not to say that every classical music performance should come with an attached fantasy play; of course not. It is merely to say that the expectation of silence in a classical music audience — and the mannered pageantries of the performer — are fundamentally at odds with our origin myths of music, from all over the world, from all different times. And even as we take these lessons from earlier times, we must do so without glorifying the past or celebrating potentially toxic lessons which we, as societies, are continuing to grow past. We must always, as artists, have a knight standing guard over our obsessions — thoughtful, loving, loyal, aware, and awake.

Music was created from the jawbone of a fish sliced in half by a sword sung into existence by a half-god legend; music was showered as a celestial gift at a feast from a half-dragon who saw true beauty in a parasol tree; and music was played by a half-mortal before a monkey, and then by a monkey before the half-mortal. I fully believe our ancient tales tell us what resides in the universal human heart when it comes to the beautiful role of music — and the expected audience reaction. We do not know if music came before story, but we do know that music came into existence by breaking the rules of all that was possible before, it came colored with devotion and generosity, and it came primarily to move the world through joy.

[1] Source link

[2] Source link

[3] Source link

[4] Of course, no research into this can be exhaustive, given the sheer volume of content into global folklore. My research has been thorough, however, and over the last several years, I have found fewer than five descriptions of the origin of story in myth and legend (in comparison with more than one hundred I have read about the origin of music). In “Myths to Live By” (1972), Joseph Campbell relays one such tale about the origins of story: according to an ancient Maori legend, the first three emotions – or base emotions – that humanity felt, once their base needs were met, were lust, grief, and fear. In order to temper and allay these destructive and raging emotions, humanity’s first invention was story.

[6] Source link