For a counter-perspective, read the companion piece to this article, “The undercommon life: Why I’m staying in academia” by Noël Wan.

Some grow up on and around army bases and call themselves “military brats.” I grew up on or around universities, so I call myself a “faculty brat.” I lived in student-family housing complexes as my dad completed a master’s and a PhD at the University of Ottawa and UCLA, respectively. Then, my life revolved around the institutions where he taught as a professor, first at the Nanyang Technological Institute in Singapore, and then ultimately, at San Jose State University. For nearly four decades I’ve been surrounded by academics from all around the world, so higher education has been a core factor in my upbringing, ideologies, and worldview.

Of course, I’ve always known the common idealized image of the academic: an elder statesperson in an armchair in front of wall-to-wall bookshelves, wearing a tweed jacket with elbow patches, only comically absent-minded, dropping nuggets of life-altering philosophy with casual frequency. This scholar was relaxedly engaged with students, unafraid of open discourse, and led conversations with consummate ease toward unexplored and dynamic territory.

And this mythical fantastic beast matched so few of the professors that I grew up around.

After all, I was always somewhat privy to everything from petty office politics to endless discussions about the drawbacks of administrations that prioritized quantitative measurement tools over qualitative student progress. From a young age, I even knew the scorn that some faculty members intrinsically hold for their students, as if these professors were destined for and entitled to a far better life, and instead now have to settle for educating those with less potential than themselves. And even the best of them were not “relaxedly engaged” with anything; they were far too busy fighting frustration with growing workloads, institutional politics, deteriorating resources, decreasing benefits for newer colleagues, and growing nationwide disrespect for the intelligentsia as a whole. Even twenty years ago, their worlds were unraveling too fast around them, and there was not enough time for Socratic discussions and high-minded pontification. They had to worry that a “too unfocused” criticism on their student evaluations would come up during their tenure review, reducing their teaching impact to Scantron bubbles rather than the unquantifiable, open-ended, and mutual explorations that were the hallmark of the best educations. The professors I grew up with already bemoaned the loss of conversation in the classroom, replaced by a unidirectional mechanistic system of prescriptive inputs that created pre-supposed outputs.

But I was not impervious. I myself romanticized academia in two critical ways.

The first was one planted in me by my father, an immigrant consistently in search of belonging, who I believe only ever felt safe in the inclusive haven of higher education. To this day, he believes that the best place to work and advance and live a good and secure life is a university. He holds deeply the value that the safest place for minorities of all kinds — even those whose thoughts are what place them in the minority — should be a university campus.

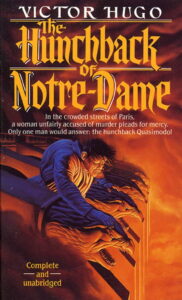

I was a bookworm child who loved literary classics like Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831). When Quasimodo saves Esmeralda from hanging and takes her to Notre Dame cathedral, yelling, “Sanctuary! Sanctuary!”, knowing she was safe in those protected walls, I imagined no Gothic church; I imagined university towers. In my impressionable childhood mind, influenced by my father’s values, I believed that within a university’s halls, no one could be forgotten, whether undergraduate, graduate, junior instructor, or tenured faculty. Everyone’s thoughts would be welcomed, efforts recognized, and voices developed. My dad raised me to believe that universities were sanctuaries for the misnamed and maltreated — the gypsies — of our time, each of whom would be protected with full-throated impassioned voice by the hunchbacked heroics of these tweed-jacket-bedecked guardians. “A professor will always protect your autonomous freedom to think,” my dad taught me.

And this romantic ideal included financial safeguard. If higher education was appropriate for a young student, they could afford it without the accrual of massive debt; perhaps they needed an additional job to make it work, but money was an obstacle, not a prerequisite. The same was true for adjunct faculty and junior instructors. Academia was a safe place to breathe, where one’s basic survival needs were met without debilitating distraction, and therefore, scholars of all ilks could dedicate themselves to higher ideals. This security allowed students and faculty members alike to become. No, not to become each other through indoctrination, but to become together via mutual challenge and discourse. And the bubble created by this equity of access, encouragement of minority thought, and constant and accurate recognition of individual contribution is what I believed made academia the closest thing to a meritocracy the real world had — one that most reliably churned out value in the form of the world’s best thinkers, researchers, and leaders.

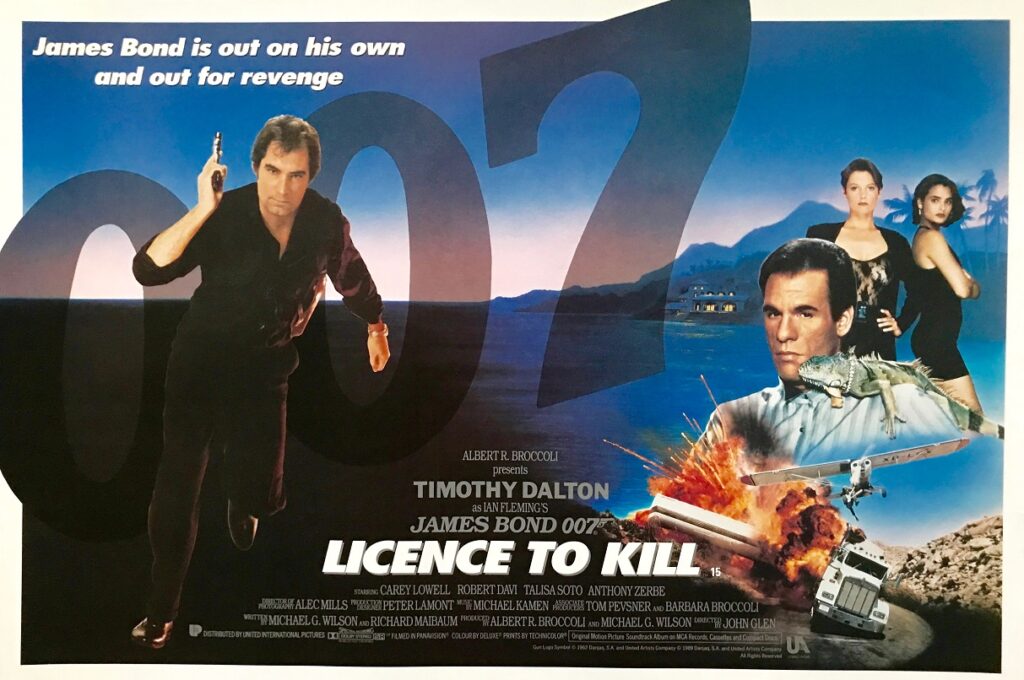

My second romanticized notion about academia was one that I came up with myself. I remember my dad took me to watch a re-screening of the James Bond film A Licence to Kill (1989) on the UCLA campus. I must have been eight or nine years old at the maximum (yes, probably a little young for that movie, but take that up with my dad). As we were walking out, a group of film students stood outside, discussing whether director John Glen had violated the compact that the Bond franchise had built with the audience by having the character be motivated by personal vengeance rather than patriotism. That’s the only sentence I heard of their discussion, but I spent the rest of the night — and in many ways the rest of my life — thinking about the term audience compact, and the exact techniques by which media makes implicit promises to an audience that were as real as anything expressed directly in the text. A few film students whom I never saw again changed my life with a few select phrases and that, for me, was also the mythos of higher education. The discussion amongst our brightest minds created a language through which all others could express and communicate that which had previously been ineffable and unshapeable. For my father, a university was a safe place; for me, in that moment, I loved it because it was a dangerous one, where attitudes, ideals, and vocabulary itself could leak out into the larger world and change the ways that everyone thought about everything. A university was a threat, I thought then with excitement, to all existing systemic structures, processes, and traditions.

The truth is, I loved academia as a child for the same reason that I loved books: they were safe spaces where I could think or be or escape into whatever I wanted, but they were incredibly dangerous in the effect they left on my thoughts when I came back into reality. As a faculty brat, that was the implicit audience compact that academia made to me. Others had the American Dream; I had an academic one.

Now, though, I am not an academic.

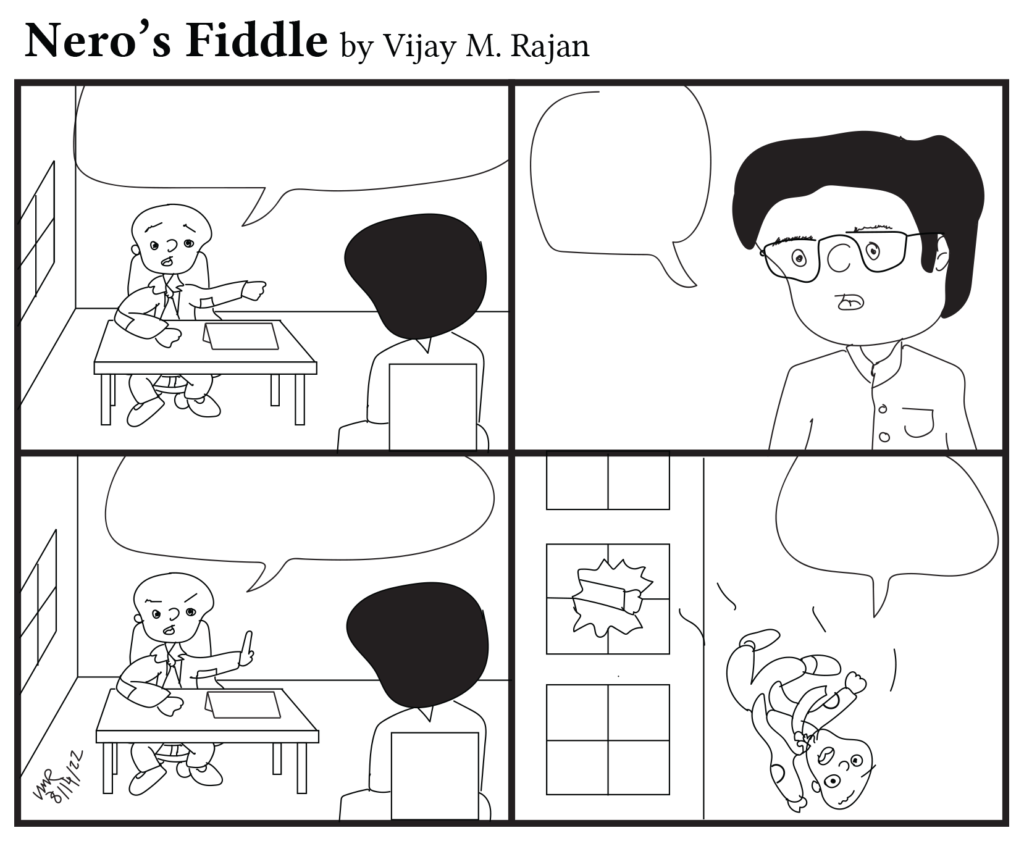

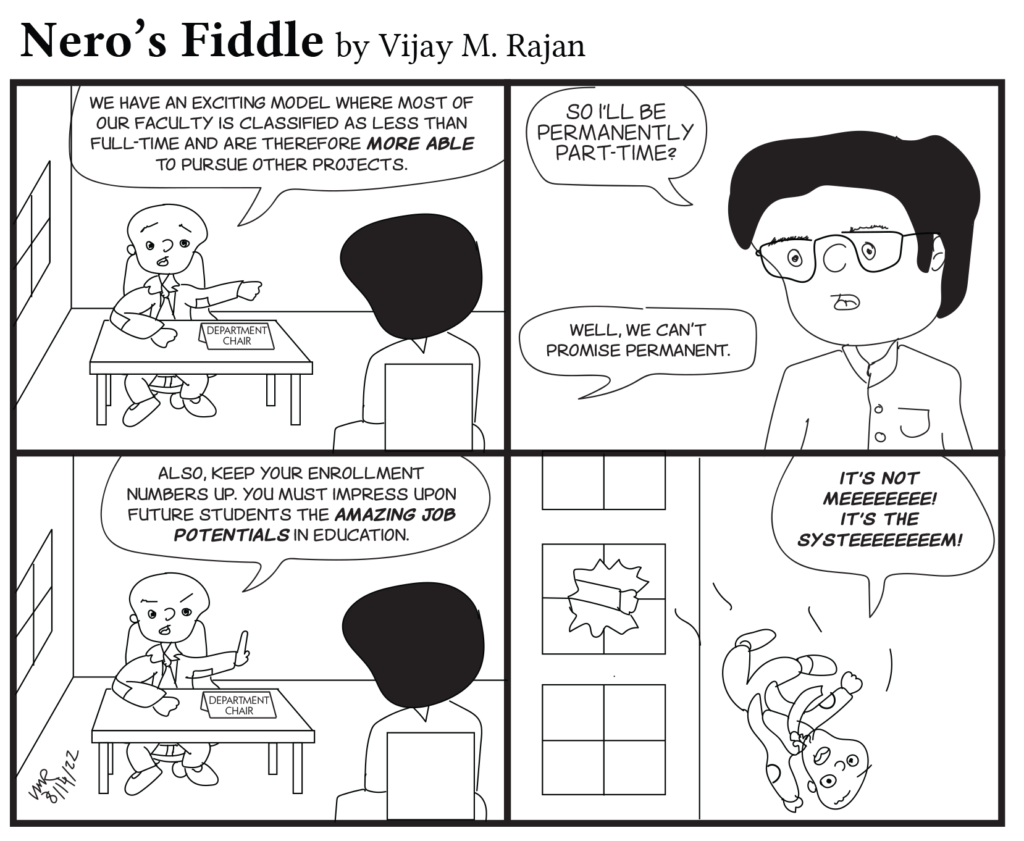

I dropped out of two different graduate programs, one arts and one business. There are many reasons why I did, but the underlying one? The further I went into higher education, the more I felt that students were only dollar signs, valuable for their number and not for their voices, and the more I saw that faculty were increasingly kept from being good teachers by a system that increasingly preferred that they be good employees first.

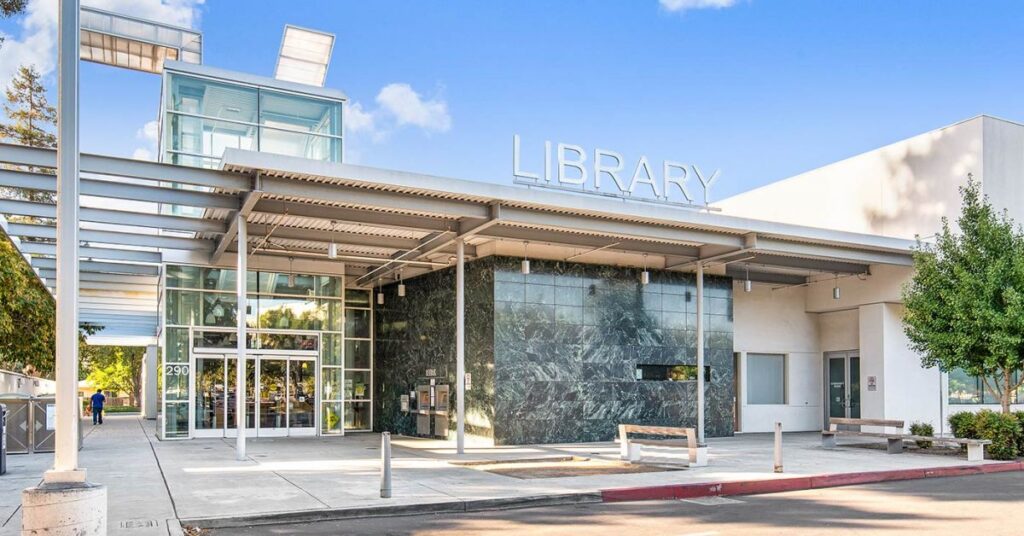

In my graduate education, I never really felt that much more security to explore non-systemic thought on campus than I did anywhere else, and I never really felt the danger of language that might actually inspire revolutionary and landmark changes within the popular zeitgeist. My final exams, even in graduate school, felt regurgitory rather than contributory. Ultimately, I ended up cutting classes and going off-campus to the public library, a place that provided both contradictory sensations of security and threat with a casual ease. I engaged with the greatest minds in any subject, leaping from thinker to thinker at a breathless pace. I could not believe the revolutionary and original thoughts to which I had access in such a public and exposed environment. Shouldn’t I have to hide when reading the James Baldwin line, “People who treat other people as less than human must not be surprised when the bread they have cast on the waters comes floating back to them, poisoned?” And then switching focus to a genre fiction novel in which Scott Turow writes, “But it’s a sad lesson, nonetheless, that we all so often lay claim to our heritage out of fear of those who once hated us and thus may do so again… After all, we are both. We are the tyrant and the democrat; the captor and the survivor; the slaveholder and the slave. We are the blood heirs to each heritage.” And then, the whiplash that resulted from picking up Carl Sagan to read, “The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.” What was magical for me about real-life libraries was that, unlike the comparatively authoritarian and ordinary Hogwarts library, no section was restricted, despite the breathless danger that I felt when entering each. Sanctuary. And danger.

It bothered me deeply that any library, even with its lack of pedagogues, so easily replaced all that I loved about higher education, and that the least I ever felt like an academic was sitting inside a classroom.

Meanwhile, back on campus, nobody was breathing easily anymore. That safety to dedicate yourself to a higher pursuit because your basic survival needs had been met felt increasingly broken. Adjunct faculty members were homeless and sleeping in their cars in parking garages. Students were working two jobs on top of school, while still accruing massive debt. The conversations were no longer high-minded; they were increasingly about getting the right answer on the test or making certain that the student got to work on time to be able to afford parking or textbooks. There was no sanctuary, and without that, there was no threat. In fact, academia had become only another funnel into the system that already existed.

My father, now already in early retirement and soon to leave the higher education system entirely, believes to this date that academia is the best place to work. On occasion, he might even send me a university staff job listing. “You can’t beat the benefits,” he always says. Perhaps it’s my fault. Perhaps I mythologized academia’s role within larger society with a childhood innocence that was naive or even ill-founded. Perhaps I should have known that I would one day have to acknowledge academia’s toothless and neutered state. Perhaps I should sympathize more with faculty members who have the impossible task of simultaneously being good employees and good leaders, working under overpaid administrators who seek to reduce the sanctuary of my childhood into just another bottom-line business. Yes. Perhaps it’s my fault.

But still… that was the audience compact I understood… and I don’t want to be forgiving, to settle for less, to stop demanding that a university be a place that creates leaders that challenge a system, not followers that simply “succeed” in one. As a faculty brat, for me, a university degree used to be more than a ticket to a picket fence; it was a licence to kill.

And if it doesn’t provide the safety to breathe or the capacity to produce the language that changes the world, then what does a university do? Make predatory Wall Street bankers? Provide a receipt that can be exchanged for a chance of success on Ziprecruiter? Give me a tweed jacket of my own behind which I can hide my more counterculture thoughts? Hmm. Works for some, I’m sure, but not for me.

So yeah, sorry you’re disappointed, Dad, but I’m not applying for that university job. Maybe it’s the fault of the child that I was, for misunderstanding what higher education was, for romanticizing that which was always perfectly unremarkable to begin with. That’s fine. I accept that. Oh well. Either way…

I’d still rather cut class, you see, and go to the library.