All photos are by the author.

Introduction

I first encountered the Nueva Canción Chilena one decade ago, in a university course that served as a very brief introduction to the various musical styles of our South American neighbors. Of the music I was exposed to, the works of Violeta Parra and Victor Jara resonated with me so deeply that they formed the catalyst for my interest in Chile, which has since evolved into regular Spanish classes with a Chilean teacher, personal study and translation of Chilean literature, and a great interest in the geography and environmental issues of this country.

I don’t believe you can know a place without touching the land, living among the people, speaking their language, and learning about their artistic traditions.

It is perhaps fitting, then, that I wrote the bulk of these words ensconced in my accommodation at the end of the world, looking over the nearby hills and mountains that make up one of the most impressive cordilleras of the globe: the Andes. From July through October 2023, I traversed ten of the sixteen vast, culturally and ecologically diverse regions of this country. I experienced Chilean earthquakes, hiked mountains in the world’s driest nonpolar desert (2 percent humidity), touched the sky at sixteen thousand feet, drove thousands of miles through Patagonian wilderness, got stranded on the road in Argentina when my pickup truck decided it had had enough, hitchhiked my way back to Chile, touched glacial ice, and ate the berries of the calafate plant. The music of the Nueva Canción Chilena accompanied me throughout. For each region alone I could write a book, but even that could not do it justice, so I have simplified my journey into three larger geographic regions: Región Metropolitana, the Atacama, and Patagonia. In each section of this article, you will learn a little about the land and find a song that reflects a person or an event.

I hope that by the end of this piece, you will have a small feel for the diversity of this country, and perhaps be inspired to take a little trip of your own. Bienvenidos a Chile and welcome to my musical journey through the Nueva Canción Chilena.

What is the Nueva Canción Chilena?

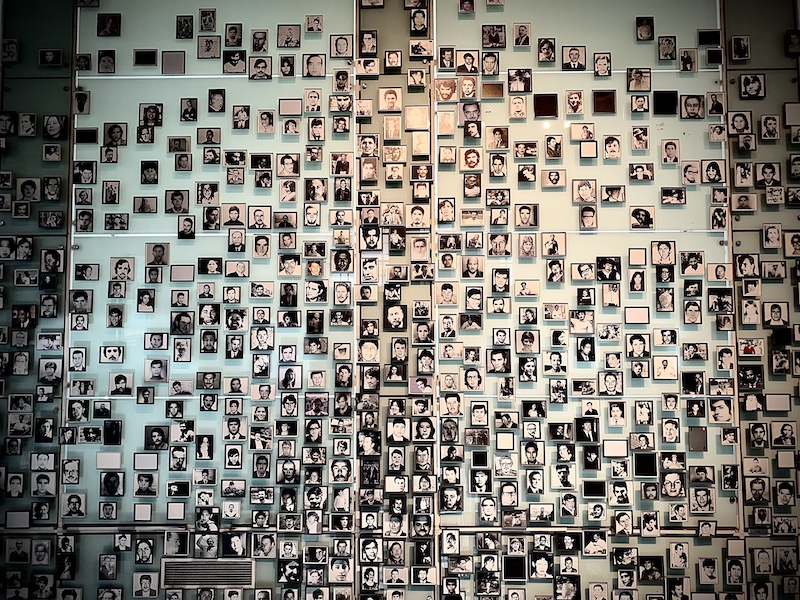

The Nueva Canción Chilena (literally “New Chilean Song”) is a genre of Chilean music that emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Heavily influenced by Chilean folk music, it reflected a renewed interest in traditional culture. The Nueva Canción Chilena was also a political movement, befitting an era of great civil unrest; it aligned itself with the presidential campaign of Salvador Allende, who went on to become South America’s first democratically elected Marxist president. The movement officially ended in 1973, when the military general Augusto Pinochet took power in a US-backed military coup. The ensuing military dictatorship oppressed musical and intellectual voices for the next seventeen years, murdered thousands, and forced many more to exile themselves abroad.[1] Though the Nueva Canción Chilena was relatively short lived, its impact was profound; it spread to neighboring Latin American countries (many of which were struggling with their own military dictatorships), and exiled artists continued to produce music from abroad, where they helped bring awareness to Chile’s political plight. Moreover, it helped build pride in national identity during a time when the region was trying to extricate itself from foreign interventionist policies.[2]

The Journey

SANTIAGO, REGIÓN METROPOLITANA

July 3. I begin my journey in Santiago, located in the middle of the country. At twenty-seven hundred miles in length, from the northern border to the southern tip, Chile is such a long country that situating the capital in the center makes sense. Not that it was done this way by design; this was merely the point where Pedro Valdivia, Spanish conquistador and first lieutenant governor of Chile, stuck the Spanish flag into what is now known as Cerro Santa Lucía (Santa Lucía Hill) and proclaimed the land for the kingdom of Spain.[3] Farther south into Chile, continued colonization was made nearly impossible by the wild Patagonian landscape and the ferocity of the Mapuches (an Indigenous group in the region), whom even the mighty Inca Empire could not subjugate.[4] To give you some idea as to the difficulty presented by the terrain: there is no road that connects Antarctic Chilean Patagonia with the rest of the country; one must drive approximately eight hundred kilometers through Argentina before reconnecting to the southern tip.

But we will get to Antarctic Patagonia in due time. For music in the Región Metropolitana, I think of Violeta Parra’s most famous song: “Gracias a La Vida” (“Thanks to Life”). While Violeta did not write this song in Santiago, the city was a central place in her life and career, and, as the capital of the country, was the location of many significant events, especially those related to the Nueva Canción Chilena and the subsequent coup that ended the movement.[5] Violeta is often referred to as the mother of the movement, as she inspired many singer-songwriters during her life and even after her death. After all, “Nothing would have been as it is had it not been for Violeta.”[6] And it is true, for without Violeta I would not be here either. So, the very first song of hers I ever heard (and in fact, the very first Chilean song I ever heard) deserves this space in my journey.

The poor yet prolific Parra family meandered all over the country in search of work, and this wandering never left Violeta’s spirit. In 1952, she traveled all over the country to collect Chilean folk music. In the process she witnessed the immense poverty in which her fellow Chileans lived, an experience that impacted her profoundly. She started composing music based on the traditional forms she encountered — music that would highlight the plight of the poor, the degradation of Mapuche lands, and the destruction of life wrought by the mining industry in the north.[7] In the tiny sala museo (museum room) of her works, a projector cycles through various clips of Violeta working, performing, and speaking. When asked what inspires her, she looks at the interviewer, with what I perceive as slight incredulity, and responds, “Todo lo que hago, lo hago por la gente” (All that I do, I do for the people).

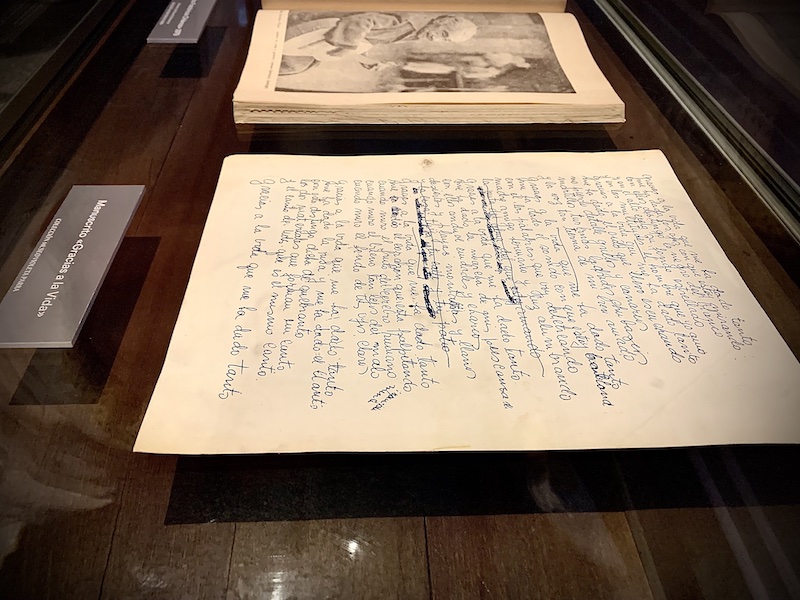

It is not possible for me to recreate her life’s journey, but I visit many places. There is, for example, her well-loved and well-decorated tumba (tomb) in Santiago’s Cementerio General, designed in such a way as to also offer a place of solace and celebration. There is also the original manuscript of “Gracias a La Vida,” housed in the Violeta Parra Museo and composed in her characteristic curved writing. This museum is situated in Parque Quinta Normal, a place in which she spent several years of her youth and subsequently attended school. In later years, she set up her peña (group or folk club), a type of community center for the arts and political activism, in the municipality of La Reina in Santiago, straddling the foothills of the Andes.[8] Parra was a well-rounded artist who also made pottery and tapestries. Parque Forestal, which slices the central part of the city diagonally, also once featured her tapestry exhibit.[9] I can think of no better backdrop to this than the massive Andes that can be seen from the park, and from nearly anywhere in the city so long as the pollution is moderate.

“Gracias a La Vida” was my entry into the world of Chilean culture. Were it not for this song, I would not have packed up my life, sold my furniture, and bought a one-way ticket to Chile. When Chileans asked what brought an American so far from home to their Chilito, I tried my best to express the importance of Violeta Parra’s music in my life.[10] They would respond, “Violeta era un genio, pero muy loca” (Violeta was a genius, but very crazy), and mime shooting their heads with a finger gun. And that is indeed how Violeta Parra ended her own life. Having had her heart broken by the much-younger Gilbert Favre (who left her to marry a Bolivian woman), she put a gun to her head and pulled the trigger.[11] Crazy? Perhaps. But I imagine Violeta existed on a heightened emotional plane. After all, this was a woman who believed that love was the only way to be free. And so, while this song is often considered a letter of gratitude toward life, it might be better and more accurately perceived as an elegy, as it was among her last compositions.

“Gracias a La Vida” by Violeta Parra[12]

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me dio dos luceros, que cuando los abro, Perfecto distingo lo negro del blanco Y en el alto cielo su fondo estrellado Y en las multitudes el hombre que yo amo Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me ha dado el oído que en todo su ancho Graba noche y día, grillos y canarios, Martillos, turbinas, ladridos, chubascos, Y la voz tan tierna de mi bien amado Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me ha dado el sonido y el abecedario; Con el las palabras que pienso y declaro: Madre, amigo, hermano, y luz alumbrando La ruta del alma del que estoy amando Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me ha dado la marcha de mis pies cansados; Con ellos anduve ciudades y charcos, Playas y desiertos, montañas y llanos, Y la casa tuya, tu calle y tu patio Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me dio el corazón que agita su marco Cuando miro el fruto del cerebro humano, Cuando miro al bueno tan lejos del malo, Cuando miro al fondo de tus ojos claros Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto Me ha dado la risa y me ha dado el llanto Así yo distingo dicha de quebranto, Los dos materiales que forman mi canto, Y el canto de ustedes que es mi mismo canto, Y el canto de todos que es mi propio canto Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Thanks to life which has given me so much It gave me two stars, which when I open them, Perfectly distinguish black from white And in the tall sky its starry backdrop, And within the multitudes the man that I love. Thanks to life, which has given me so much. It gave me hearing that, in all of its reach Records night and day crickets and canaries, Hammers and turbines, bricks and storms, And the tender voice of my beloved. Thanks to life, which has given me so much. It gave me sound and the alphabet. With them the words I think and declare: “Mother,” “Friend,” “Brother” and light shining down on the road of the soul of the one that I love Thanks to life, which has given me so much. It gave me the steps of my tired feet. With them I have traversed cities and puddles Valleys and deserts, mountains and plains. And your house, your street and your garden. Thanks to life, which has given me so much. It gave me this heart that shakes its frame, When I see the fruit of the human brain, When I see good so far from evil, When I look into the depth of your light eyes… Thanks to life, which has given me so much. It gave me laughter and it gave me tears. With them I distinguish happiness from pain The two elements that make up my song, And your song, as well, which is the same song. And everyone’s song, which is my own song. Thanks to life which has given me so much

If you wish to know more about Violeta and the 1973 coup, these might interest you:

- Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Museum of Memory and Human Rights), featuring exhibits about the 1973 coup, the subsequent dictatorship, and the return to democracy. Located near Parque Quinta Normal.

- Violeta se fue a los cielos (Violeta Went to Heaven), a biopic about Violeta Parra.

LA ATACAMA

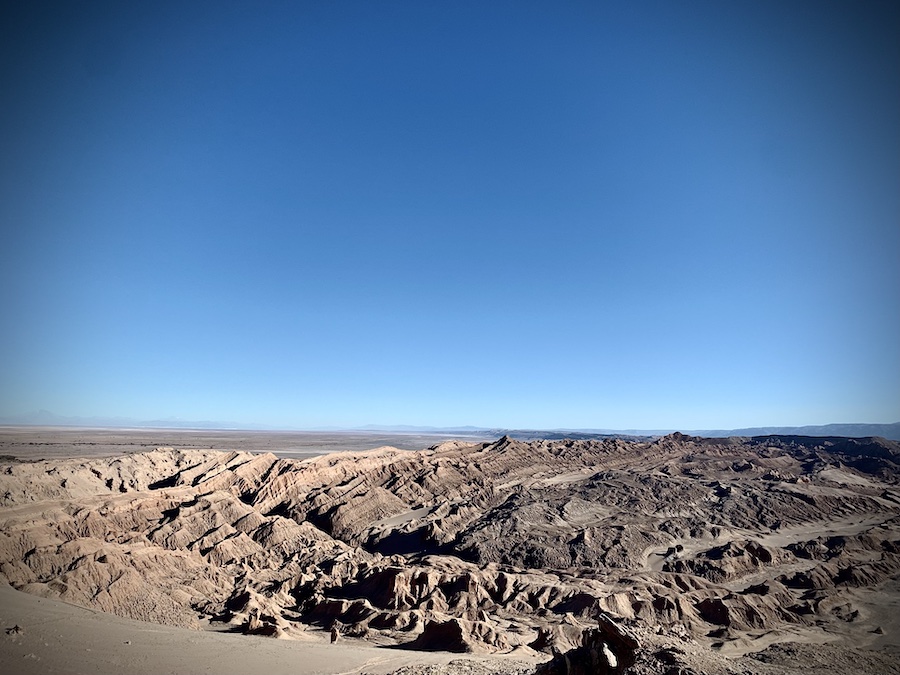

July 31. On an unseasonably warm day during the austral winter, I find myself in the Atacama, the world’s highest, driest nonpolar desert. In fact, only some places in Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys are drier than where I stand.[13] My journey takes me to San Pedro de Atacama, a little tourist town that launches visitors into the far reaches of the Chilean and Bolivian altiplano. Situated between two small rivers, the Ríos San Pedro and Vilama, San Pedro boasts a generous 10 percent humidity. Once you leave the town, this quickly drops to 2 percent. Even breathing is painful. Dominating the landscape is Licancabur, a stratovolcano which straddles the Chilean-Bolivian border. The Atacameños worshipped Licancabur and other high volcanoes; to climb it supposedly brought misfortune and was actively discouraged.[14] I don’t entertain ideas of climbing Licancabur, but that doesn’t stop others, even though landmines litter the base of the Chilean side and frequent landslides obliterate climbing routes on the Bolivian side. Perhaps Licancabur is protecting itself from destructive outdoor tourism practices. In the quiet solitude of the desert, Licancabur isn’t the only thing being desecrated.

Desert landscapes are often utilized (and destroyed) for the resources contained within, from copper to petroleum. Once upon a time, these landscapes used to be at the bottom of the sea, accumulating organic matter and minerals over millions of years.[15] When plate tectonics push these ancient ocean beds into desertification zones, evaporation occurs, leaving the minerals behind.[16] The Atacama is a mineral hot spot (with Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni containing an estimated 50 to 70 percent of the world’s known lithium reserves) and most of this desert lies within Chile’s political borders.[17]

And thus, Chile is today the world’s largest producer of copper and second largest producer of lithium. Dig some more and you’ll find other riches: iodine, rhenium, lithium, molybdenum, silver, salt, potash, sulfur, and iron ore — the list goes on.[18] Chile has had an extractive society since the 1500s, when the Spaniards sought silver and gold.[19] For many years the mines were owned and operated by foreign entities, leaving Chileans with little revenue. The work was hard and the conditions were poor.

From the nineteenth century onward, Chilean society faced a “social question” (as it was referred to) — the deteriorating working and living conditions of the mining centers.[20] Miners struggled for better conditions and equitable pay but were often met with resistance from political entities. Of the many disputes between miners and the authorities, the nitrate miners’ strike in 1907 was particularly significant; it is known as the Santa María School Massacre. Striking miners, their wives, and their children gathered peacefully in the Santa María School to protest their working and living conditions. They were massacred by the Chilean army. The victims were buried in a mass grave as part of the government’s attempt to hide details regarding the tragedy.[21]

Over time those details came to light, as often details do, and this event became the subject of many Chilean songs. Santa María de Iquique, Cantata Popular was composed in 1969 by Luis Advis Vitaglich. He combined classical and folkloric elements to produce this cantata, which was popularized by Quilapayún’s interpretation of the piece.[22] The final song, featured here, voices the miners’ demands to end exploitation. Unlike the ending of this real-life tragedy, this cantata ends with the hope of an egalitarian and free world, perhaps a hope many Chileans held at the time (and perhaps a hope many still hold onto today).

“Canción Final” from Santa María de Iquique, Cantata Popular by Luis Advis Vitaglich, performed live by Quilapayún[23]

Ustedes que ya escucharon la historia que se contó no sigan allí sentados pensando que ya pasó. No basta sólo el recuerdo, el canto no bastará. No basta sólo el lamento, miremos la realidad. Quizás mañana o pasado o bien, en un tiempo más, la historia que han escuchado de nuevo sucederá. Es Chile un país tan largo, mil cosas pueden pasar si es que no nos preparamos resueltos para luchar. Tenemos razones puras, tenemos por qué pelear. Tenemos las manos duras, tenemos con qué ganar. Unámonos como hermanos que nadie nos vencerá. Si quieren esclavizarnos, jamás lo podrán lograr. La tierra será de todos también será nuestro el mar. Justicia habrá para todos y habrá también libertad. Luchemos por los derechos que todos deben tener. Luchemos por lo que es nuestro, de nadie más ha de ser.

You who have already heard the story that was told, do not continue sitting there thinking that it has already happened. Just remembering is not enough, crying is no longer enough. It's not time to lament, when it's time to fight. Maybe tomorrow or the day after or, in a while, the story you have heard will happen again. Chile is such a long country, a thousand things can happen if we do not prepare resolutely to fight. We have pure reasons, we have to fight. We have hard hands, we have the means to win. Let us unite as brothers that no one will defeat us. If they want to enslave us they will never be able to do it. The land will be everyone's, the sea will also be ours. There will be justice for everyone and there will also be freedom. We fight for the rights that everyone should have. Let's fight for what is ours, it should belong to no one else.

LOS LAGOS, PATAGONIA COSTA

August 14. When people think of Patagonia, they probably think of the end of the world, untouched natural landscapes, and Torres del Paine (towers of blue), the crown jewel of all of Chile’s national parks.[24] Or perhaps they think of Tierra del Fuego (land of fire), where the long-vanquished Indigenous tribes never let their fires die out, deceiving the European explorers into thinking the land was ablaze.[25]

Or perhaps they think of Ushuaia or Punta Arenas, from where the boats depart to the local penguin colonies and Antarctica. Patagonia is as difficult to describe in words as it is to accurately map. The Chilean side of Patagonia is divided into three parts: Patagonia Costa, Patagonia Verde, and Patagonia “Proper.” It’s a little confusing. Even Chileans are not exactly sure where Patagonia begins.[26]

I am starting in Los Lagos, the “beginning” of Patagonia, which perhaps some would not consider Patagonia because it is not quite the end of the world. But that matters little to me. For here lies the beginning of the Carretera Austral, a dead-end road into the depths of Chilean Patagonia, where civilization ceases and from which one must cross into Argentina to reemerge into the land of humans. Here lies the confluence of multiple cultures — German immigrants, Chilotes, and Mapuches — to create a distinct culture that is not really Chilean. Or perhaps it is more authentically Chilean than anywhere else in the country. Here lies the southernmost major city in Chile: Puerto Montt.[27]

We must go back in time now, to a different Puerto Montt than the one I have come to know. We must return to the year 1969, the same year Luis Advis Vitaglich composed his Santa María de Iquique, Cantata Popular. For a large swath of the Chilean population, life was no better in 1969 than it was in 1907. There was insufficient housing to support the growing rural-urban migration and many people lived in campamentos (shantytowns) throughout the country. Frequently, people simply seized land and built shacks.[28] It certainly wasn’t legal, but as Chile was in the midst of a land reform crisis, and as the politicians offered no solutions, people took matters into their own hands.

In 1969, about ninety poor families squatted on land near Puerto Montt. There had been no immediate action to evict them, and the campamento residents negotiated with the government to legally occupy the land.[29] All seemed promising for several days, the hope being that the land would eventually be legally acquired. Then, in a sudden turn of events, the carabineros (police) approached the encampment to evict the squatters, who were armed only with sticks and stones.[30] The carabineros quelled the uprising with carbines and tear gas, killing ten or eleven people and injuring about fifty others.[31] At the time, it was uncertain where the political responsibility lay, but the blame was later pinned on the then Minister of the Interior, Edmundo Peréz Zujovic, who would be assassinated in retaliation two years later by a left-wing guerilla organization.[32] While Zujovic did approve the removal of the settlers, it is uncertain whether he ordered the police to shoot. This event further deepened the divide in Chilean politics, which resulted in the 1973 coup d’etat.[33]

Much like the 1907 Santa María School Massacre, the Massacre of Puerto Montt persisted in artistic memory. Conceptual artist Luis Camnitzer created an art exhibition named Massacre of Puerto Montt (1969) that is now on display at the Reina Sofía National Art Center Museum in Madrid, and Paulo Vargas Almonacid released a documentary in 2010 called Ni todas la lluvia del sur, which translates to “neither all the rain in the south.” The title of this documentary is pulled directly from the lyrics of a Victor Jara song, from his 1969 album Pongo en tus manos abiertas (I put into your open hands). The song in question, “Preguntas por Puerto Montt” (Questions for Puerto Montt), condemns the massacre and openly blames Zujovic for ordering the violence.

Victor Jara was born to tenant farmers, but his mother, a mestiza with Mapuche ancestry, performed folk songs at local weddings, becoming a source of Victor’s affinity for music.[34] A meeting with Violeta Parra in 1957 further inspired Jara, and he continued his exploration of Chilean folk music. He later performed with Violeta Parra’s son, Ángel Parra, which launched him into the Nueva Canción Chilena movement. Jara had a knack for irritating right-wing Chileans through music that addressed social and political themes, and it was no shock that he joined the Communist Party and aligned himself with Allende’s presidential campaign.[35] As violence escalated throughout the country, Jara’s music became increasingly political, and he received both national and international acclaim and recognition.

On the day of the coup, Jara was taken to the Estadio Chile alongside many others. He was easily recognizable due to his fame and was quickly removed from the group. After hours of torture, he was executed. His body, riddled with bullets, was displayed outside the stadium for incoming prisoners to see.[36]

“Preguntas por Puerto Montt” by Victor Jara[37]

Muy bien, voy a preguntar por ti, por ti, por aquel por ti que quedaste solo y el que murió sin saber Muy bien, voy a preguntar por ti, por ti, por aquel por ti que quedaste solo y el que murió sin saber y el que murió sin saber Murió sin saber por qué le acribillaban el pecho luchando por el derecho de un suelo para vivir, ay, que ser mas infeliz el que mando disparar sabiendo cómo evitar una matanza de vil Puerto Montt oh, Puerto Montt (x 4) Usted debe responder señor Pérez Zujovic: ¿por qué al pueblo indefenso contestaron con fusil? Señor Pérez su conciencia la enterró en un ataúd y no limpiarán sus manos ni toda la lluvia del sur ni toda la lluvia del sur Murió sin saber por qué le acribillaban el pecho luchando por el derecho de un suelo para vivir, ay, que ser mas infeliz el que mando disparar sabiendo cómo evitar una matanza de vil Puerto Montt oh, Puerto Montt (x 4)

Very well, I will ask for you, for you, for that one, for you who were left alone and the one who died without knowing Very well, I will ask for you, for you, for that one, for you who were left alone and the one who died without knowing and the one who died without knowing Died not knowing because they riddled his chest fighting for the right to a plot of land to live, oh, to be unhappier the one who ordered fire knowing how to avoid a vile massacre Puerto Montt oh, Puerto Montt (x 4) You must respond, Mr. Pérez Zujovic: Why did they answer the helpless people with rifles? Mr. Zujovic, you buried your conscience in a coffin and it will not clean your hands not even all the southern rain not even all the southern rain He died not knowing because they riddled his chest fighting for the right to a plot of land to live, oh, to be unhappier the one who ordered fire knowing how to avoid a vile slaughter Puerto Montt oh, Puerto Montt (x 4)

Update: In June 2016, a Florida jury found Pedro Barrientos liable for Jara’s murder. His US citizenship was revoked in July 2023 and he was deported to Chile in December 2023. He is now in custody.[38]

Conclusion

October 14. The austral winter has ended, and spring is coming, even to the permanently ice-capped far reaches of Patagonia. It isn’t just the small buds on the flowering trees that give it away. Nor the fact that all the boats are getting ready to take visitors to the penguin colonies. Or that the tours to Antarctica shall begin shortly. Despite the crispness in the air, it simply smells like spring. And with spring, I’ve come to say my goodbyes to a country that will remain close to my heart until the end of days.

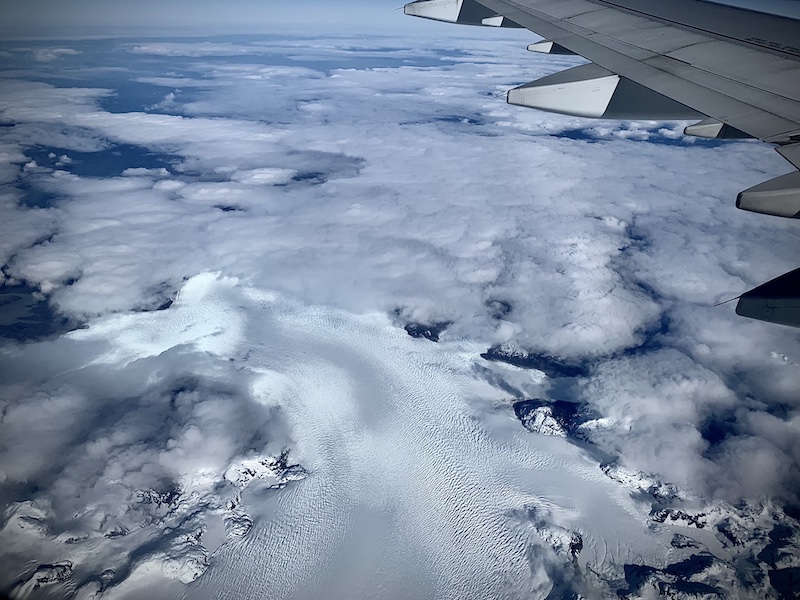

From thirty thousand feet in the air, I can see the tongues of the immense glaciers as our plane from Punta Arenas passes over the Northern Patagonian Ice Sheet. From this vantage point, I notice the curves of the icy rivers, the accumulation zone, and the terminus. I can see the moraines and crevasses, just tiny slivers from up here. I see where the icebergs calve into frigid, gray glacial waters.

Everyone else is asleep on this morning flight, so it is just me and the glaciers. I send a silent prayer. I hope you will still be here by the end of my life and beyond. And truly I hope so. Not simply for the sake of planetary health but because you and your children and your children’s children deserve to know a world with glaciers, a planet whose far reaches are still relatively unexplored. I never take my eyes off those glaciers, still craning to see them even once we have long passed over the Ice Sheet.

There is a legend in Patagonia that states that if you eat the berries of the calafate plant, you are destined to return to this rugged landscape. Well, I’ve more than had my fill of calafate berries, so I’ll surely be back. Even as I write these words, there is a melancholy deep in my heart as I think about the places I’ve been and how they are currently out of reach. Sometimes I still wake up early in the morning, with somewhat hazy thoughts of needing to drive into Puerto Montt for groceries, or that I ought to take one last bike ride through the Atacama before departing. Except I am not there anymore. I can see how Violeta Parra and Victor Jara felt an immense love for their land, and why they chose to sing about these landscapes and elevate the Chilean people, even though they had the opportunity to settle abroad and live in relative safety. Their music magnified my love for a place and in visiting that place and walking where they walked, the landscape magnified my love for their music.

I don’t believe you can know a place without touching the land, living among the people, speaking their language, and learning about their artistic traditions.

But if you can do this, I believe history becomes more than just events in linear time, more than something you simply read about in a textbook. It becomes a tangible event in a physical space that you can experience despite the temporal distance separating then from now.

From my AirPods Victor Jara’s “Manifiesto” plays.

“Manifiesto” by Victor Jara[39]

Mi canto es de los andamios Para alcanzar las estrellas Que el canto tiene sentido Cuando palpita en las venas Del que morirá cantando Las verdades verdaderas No las lisonjas fugaces Ni las famas extranjeras Sino el canto de una lonja Hasta el fondo de la tierra Ahí donde llega todo Y donde todo comienza Canto que ha sido valiente Siempre será canción nueva

My song is of the scaffolding To reach the stars. For a song has meaning when it beats in the veins of one who will die singing the real truths Not of fleeting flattery Nor of foreign fame It is for this narrow country to the depths of the earth There, where everything ends And where it all begins I sing that of that which has been brave which will always be the canción nueva

[1] Information gathered through past studies and from my trip to the Museo de la Memoria y Los Derechos Humanos (Museum of Memory and Human Rights), located in the historic center of Santiago.

[2] Morris, Nancy, “Canto Porque es Necesario Cantar: The New Song Movement in Chile.” Latin American Studies Association 21, no. 2 (1986): 117–36.

[3] Insight Guides: Chile and Easter Island (London: Insight Guides, 2019), 133.

[4] Ibid, 29.

[5] It was composed in La Paz, Bolivia.

[6] Krebs Merino, Patricio; Corces, Juan Ignacio. “Entrevista exclusiva: Silvio Rodriguez,” La Bicicleta (1986): 24.

[7] “Trayectoria,” Fundación Violeta Parra, http://www.fundacionvioletaparra.org/trayectoria.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] An endearing term used by Chileans to refer to their country. It means little Chile.

[11] Arcos, Betto. “In ‘Violeta Went to Heaven,’ A Folk Icon’s Tempestuous Life.” NPR, 13 July 2013, https://www.npr.org/2013/07/13/201227290/in-violeta-went-to-heaven-a-folk-icons-tempestuous-life.

[12] Lyrics from https://lyricstranslate.com/en/gracias-la-vida-thanks-life.html-0, with translation adjustments by the author.

[13] Nevres, M. Özgür, “Top 10 driest places on earth.” Our Planet, November 9, 2015, https://ourplnt.com/driest-places/.

[14] Le Paige, Gustavo (1978-01-01). “Vestigios arqueológicos incaicos en las cumbres de la zona atacameña“. Estudios Atacameños 6: 36–52, https://revistas.ucn.cl/index.php/estudios-atacamenos/article/view/167.

[15] “Physical Geography | How Salt Shapes Our Lives,” The Salt Association. April 4, 2020, https://saltassociation.co.uk/education/physical-geography/.

[16] Anderson, Roger N, “Why is oil usually found in deserts and arctic areas?,” Scientific American, January 16, 2006, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-is-oil-usually-found/.

[17] Keating, Joshua (2009-10-21). “Bolivia’s Lithium-Powered Future: What the global battery boom means for the future of South America’s poorest country,” Foreign Policy, October 10, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20140917190536/http:/www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2009/10/21/bolivias_lithium_powered_future.

[18] USGS Production Statistics (2021)

[19] Hutchinson, Elizabeth Quay, Thomas Miller Klubock, Nara B. Milanich, and Peter Winn, editors. The Chile Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

[20] Grez, Toso, La “Cuestión Social” en Chile ‘ Ideas y Debates Precursores (1904 – 1902). (Santiago, Chile, 1995), opening sentence: “fenómenos que a partir de la década de 1880 fueron conocidos bajo el nombre de «cuestión social».

[21] Hoehn, Marek (2007). “Una visión comparativa sobre la huelga de Santa María de Iquique y el legado de los movimientos obreros de la época,” in La Masacre de la Escuela Santa María de Iquique: Mirada Histórica desde la Cámara de Diputados. Santiago: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2007), 110.

[22] Quilapayún is the longest-lasting ambassador of the Nueva Canción Chilena. Formed in 1965, they continue to perform today.

[23] Translation done by author with the assistance of Google.

[24] Torres comes from the Spanish word meaning “towers” but paine means blue in the native Tehuelche (Aonikenk) language, an interesting fact I learned during my travels.

[25] Bridges, Lucas. The Uttermost Part of the Earth. (Editorial Südpol, Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, República Argentina, 1948 reprint 2019).

[26] This is information Chileans have directly told me.

[27] Punta Arenas lies farther south but is geographically isolated from the other major cities in Chile: Santiago, Puerto Montt, and Iquique.

[28] Hutchinson, Elizabeth Quay, Thomas Miller Klubock, Nara B. Milanich, and Peter Winn, editors. The Chile Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

[29] Salvo, Manuel Salazar, “50 años de la Matanza de Pampa Irigoin en Puerto Montt”. Interferencia. March 9, 2019, https://interferencia.cl/articulos/50-anos-de-la-matanza-de-pampa-irigoin-en-puerto-montt.

[30] As far as I am aware, los carabineros is a term used specifically in Chile to refer to the police. You may hear other words in different Latin American countries.

[31] The exact numbers are disputed.

[32] “Assassination Felt Solved After Fight,” Spokane Daily Chronicle. June 14, 1971, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=jkQzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=c_gDAAAAIBAJ&pg=4043%2C4222468.

[33] Loveman, Brian, Las Ardientes Cenizas Del Olvido: Vía Chilena de Reconciliación Política 1932 – 1994, (Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 2000), 359.

[34] Jara, Joan. Víctor: An Unfinished Song (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1984), 24-27.

[35] Lynskey, Dorian, “Victor Jara: The folk singer murdered for his music,” BBC, Aug 12, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200812-vctor-jara-the-folk-singer-murdered-for-his-music.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Translation via Google and the help of the author.

[38] “HSI Space Coast locates, arrests Chilean wanted for torture, extrajudicial killings,” U.S. Immigration and Custom Enforcement, October 10, 2023, https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/hsi-space-coast-locates-arrests-chilean-wanted-torture-extrajudicial-killings.

[39] Translated by author with assistance from Google.

Mona,

A very poignant essay rich with personal reflections informed by the tender music and histories of those that resonated with you. I want to read more of your work.

Kerm