Introduction

“For the Conservatory, I would next like to do a musical adaptation of The Jungle Book,” Vinita said. My face twisted into a pained grimace. Luckily, she couldn’t see it since I was working from home (the pandemic had just recently begun). I was the Director of Education for EnActe Arts, a Bay Area theatre company. Vinita was the Artistic Director.

The Conservatory was a program in which students of all ages (some as young as six, most in middle and high school, with only a few adults) would be guided through writing, staging, and presenting a full theatrical production to audiences. That meant that it was my job to guide the adaptation of the work, essentially serving as head of the writers’ room and ensuring that we had a great script at the end of the process. And a musical, no less.

I decided to keep my reservations largely to myself, knowing that the book was well-beloved, and as always, appreciating the challenge of finding my way into work that was not inherently attractive to me. I considered my own judgments. Why did I hate The Jungle Book? Structurally, I found Mumbai-born Rudyard Kipling’s storytelling haphazard and episodic, but that was something I could easily see working past.

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe, Such boastings as the Gentiles use, Or lesser breeds without the Law Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget - lest we forget!Rudyard Kipling, “Recessional”

There was also no question that Kipling was an unapologetic imperialist. His poems “White Man’s Burden” and “Recessional” are execrable treatises of British responsibility, superiority, and right to rule. But even imperialism has inside of it a toxic love. The truth was, in the late 1800s, Kipling loved India and Indians much more than many of his peers; he freely admitted to adapting several of his stories and the very concept of animal-fables from The Panchatantra and The Jataka Tales, well-known ancient Indian folklore. Concepts like cultural appropriation or even the inherent injustices of segregationist thinking were for future generations to discover. As racist as Kipling seems now, many of his own British compatriots thought of him as not nearly white supremacist enough. My hesitations were not political; in fact, I believed updating the work of such a problematic and influential figure was filled with potential. So why, on some visceral level, didn’t I want to be connected to The Jungle Book?

I realized there were two reasons.

Number one, throughout my childhood, most of my friends’ exposures to India were through Hollywood; I can’t count the number of times I was asked if my family back home rode elephants to work or ate chilled monkey brains. The last thing I wanted was for my American friends to imagine that every time I visited India, I pranced around in a red loincloth with wild animals in the jungle. Somehow, The Jungle Book property had become a cultural ambassador for the country in which I was born, promoting ideologies in which the subcontinent itself had no voice. Even the name Mowgli, though Kipling claimed in the work it meant “frog,” has no Indian source or meaning; it was just a nonsense word made up by Kipling. And yet for so many Western audiences, it has become the first “Indian” name they know. I felt an automatic hesitation to associate with any material that had so stereotyped my upbringing.

Two, Kipling’s central thesis had always fundamentally bothered me. As an immigrant raised between two worlds, raised equally on The Panchatantra and Aesop’s Fables, I should have been the primary audience for his work. But the book failed completely to mirror my own experience, the deep sense of simultaneous belonging I felt to two different cultures, and the balance I walked daily between the two. I never felt like Kipling nailed what it felt for one to feel dual citizenship even while being constantly pressured by external forces to fit more fully within one culture or the other. The Jungle Book asserts Kipling’s belief that while one may visit and feel great affection for people of other races, ultimately, they belong with their own kind. I could get along with Americans, learn their ways, have fun with them, but in the end, I should go back to “my” people.

Again, I remembered the visuals of the ubiquitous Disney adaptation where, after all of his adventures with the animals, all it took for Mowgli to want to reintegrate into human society was a girl’s twitching hips and batted eyelashes. It was a confoundingly simplistic and stupid take on belonging.

I expressed a few of these hesitations as obstacles to be surmounted, and Vinita went on, “The fact that the text is problematic is why it’s perfect. We can do a modern version. A Jungle Book 2.0. After all, the original is not very authentically South Asian.”

That made me cringe more. Growing up, I’d hated that it was Indian at all, this too-popular albatross I had to be associated with though I never wanted to be. And now it would be more Indian? On some level deeper inside myself than I could yet completely articulate, I couldn’t help but react negatively to the idea of having my name attached to any version of The Jungle Book. But when it comes to writing, there’s one rule that I arduously follow: any time I hesitate to be involved in a project based on emotional rather than logical objections, then that is the work I must move toward. None of the problems I had with the text were logically insurmountable so I had no choice.

I heard myself say, “This sounds like a great idea. If we do it right, it’ll be a terrific spectacle.”

My self-colonization

Though born in India, I moved to the Americas when I was four years old. Throughout my childhood, I visited India frequently. Soon, I was comfortable in either environment — but I made sure these two cultures did not intersect in overt ways. They were two unconnected halves of my self; I came to see any overlap as dangerous. Over the past fifteen years, I have begun to recognize that this burning need to keep the two halves of my identity separate but equal was a result of my own colonization. (What a mind-bending realization, to know that I did to myself what others had historically forced upon my people.) I want to tell a few stories from my childhood and adolescence that illustrate why I felt this need to self-colonize.

One: when I, as a child, heard about the kerfuffle involving Crayola branding its peach-colored crayon as “flesh”-toned, I was as taken aback as many of my white peers. Believe it or not, in elementary school, I had been shading my hand-drawn people that default peach color myself, without any reluctance or objection. I had so thoroughly separated my Indian identity from my American one that within the school schema, skin color variation had ceased to exist within my mind. Also, in my early fiction-writing, most of my leads were white people — and my stories were very devoid of anything that could remotely be considered global or Indian. I learned early that the best way to “assimilate” into American culture was to present as familiar a face as possible.

Yes, in the privacy of my parents’ home and on our trips to India, I was familiarizing myself with the Mughal empire in Amar Chitra Katha comics, speaking and reading and writing Tamil fluently, enjoying Indian food, setting off firecrackers during Diwali, and falling in love with the Hindu epic The Mahabharata — but around my American friends, I listened to only American music, talked about only American movies, ate only American food.

If Hollywood was determined to paint me as exotic, then I would do what I could to be as unexotic as possible. It became a core survival instinct. This introduced a psychological separation between my parents and myself as well. When friends came to my house, I wished my mother wouldn’t wear sarees. To take another example, my parents, feeling no need to have a fireplace, had walled it up and used it instead as a Hindu prayer altar. Every time my friends reacted in surprise, I found myself waving to them as if to communicate wordlessly, “That’s just my parents; it’s not me.”

Two: the one time that I did try to express my Indian side backfired hard. I was one of the few Indians in my high school in a predominantly white suburban area in South San Jose. Freshman year, we were supposed to bring in a song that we liked for a music appreciation class, and I don’t know what compelled me, but I brought in a Tamil song I loved. I remember how, as the music played, half the class fell into an uncomfortable silence and half into derisive laughter. I got through the rest of my presentation as quickly as possible, and decided if there was a next time, I’d just shut up and bring in a song by Green Day instead.

Three: in my first screenwriting class in college, I submitted an ensemble piece featuring a lead cast of mostly white male and female characters. Even the lead characters that were minorities (and none of them were Indian, of course) were highly assimilated, as reflected in my own friend groups. My professor called me into his office and extolled the benefits of writing what you know. I understood at once the underlying message of what he meant: you are a foreigner, you cannot possibly understand and write “default” Americans, so you should write about Indians. “I am American; America is what I know,” I wanted to snap, knowing that if I ever did write anything related to South Asia, I would be stereotyped into being “the Indian writer” instead of being able to aspire to simply be “a writer.”

Four: in the Indian community, those of us in the first generation of immigrants were frequently scornfully called ABCD (American Born Confused Desi) by the more “authentically” Indian generation before us. Though technically I was not American-born, apparently, I had moved here young enough to fit the label. I hated that term. I did not feel confused by anything. I felt perfectly comfortable in Indian circles, and I also felt at home in non-Indian circles. I knew who I was. Hell, I knew both worlds to a degree that they couldn’t fathom; after all, I was code-switching like an expert.

The point I am making with these stories is not that I was confused or broken, but that external voices wanted me to be. I always felt like I belonged to both. I just chose when to turn one or the other off. When in one environment, I never felt a loss or a longing for the other; I just understood that most Indians and Americans wanted me to be incomplete in either culture. There was a fundamental belief that I should fully belong in only one, that culture was somehow not like language, that while bilingualism was an aspiration, biculturalism was an impossibility. Individual multiculturalism, even though that is what describes me best, was a double-edged sword. I knew that if my friends understood that I was completely at home watching a three-hour Bollywood movie or praying at a fireplace, I could not be so fully one of them. I also knew that if my extended South Asian family or my parents’ friends caught me listening to U2 instead of A.R. Rahman, they would consider me incompletely Indian. I was told I did not have the right to completely inhabit either culture.

“He’s not really Indian,” my white friends would say with dismissal or relief. “He’s not really Indian,” my extended family and uncles and aunties would say with dismissal or derision.

(I recognize that things have changed now; it’s amazing to me how many South Asian kids are in Bay Area schools, and how much the youngest generation champions cultures from around the world, and how multiculturalism no longer necessarily comes with a side of embarrassment. This makes my experience even unique from my nephews’ and niece’s. First-generation immigrants stand alone, disconnected from their parents’ more natural foreignness and their children’s unquestioned assimilation.)

So. I self-colonized.

Being overtly Indian didn’t seem worth the cost or the effort. I let it go, surrounding myself with close friends from every other part of the world, throwing mental roadblocks myself against close associations with South Asian peers. I let it be enough that I was Indian on the inside, known only to myself. I knew how East Asian storytelling act structures affected every story I wrote; I knew how my American political worldview was influenced by an intimate knowledge of another country’s history; I knew that I spoke and read and wrote Tamil even better than so many of my cousins growing up in Tamil Nadu; all of that had to be enough. To reveal my Indianness only brought trouble, judgment, and even career stereotyping. I made a conscious choice. Since America was my home, I would mostly only participate in and express my American half.

While my sister had an arranged marriage, my parents never even brought it up with me. To their credit, my parents never doubted my Tamil identity; any conflicts between us had very little to do with their understanding of my ethnic assimilative identity. As I grew older and moved away from Indian popular culture, though, I know my mother did miss talking to me about Indian films, troubled that I cared to connect in fewer and fewer ways in the language in which she was most comfortable. But that’s the life of an immigrant — one in which your children are guaranteed, by your own choices, to increasingly become strangers to your world.

My subversive Indianness

I must admit, though, that this summary of my self-colonization lacks the necessary nuance. Because there were ways in which the two halves of my identity intersected; it was just in secret ways. I was always Indian subversively. When I struggled with poetry in college, having always been more natural with prose, I used the syllabic linguistic structures of Tamil as the breakthrough cryptography by which to understand sonic assonance. (For example, I never understood Tolkien’s contention that “cellar door” was a particularly beautiful phrase until I wrote the syllables out in Tamil, read them as a foreign speaker, parsed out my aversion, and reappraised the letter “r” from within Tolkien’s Eurocentric context.) When I made my short film Withdrawal (2015), I directed my lead actor during a moment where his character had just lost his wife, to act with the subtext that I had seen the actor Kamal Haasan use in the film Nayakan (1987) — because that was still the most primal expression of on-screen grief I had ever witnessed. When I wrote my very first fantasy story, the only way I could think to make it as meaningful as I wanted was to construct it around the four acts of dharma, kama, artha, and moksha, a story structure initially espoused in the ancient Upanishad, seismically different from anything proposed by Aristotle or Freytag. No one ever knew how I channeled my South Asian upbringing into American assimilative competence, not even my significant others or closest family. On many levels, I enjoyed that the intersection between the two halves of my identity was my own personal secret. I had rebelliously recognized that embedding my South Asian heritage as subtext within a Western candy coating was the secret loophole by which I could claim what I knew I was owed. Time and time again in my life, I have found that what has made my work successful to Western audiences was my drawing upon my secret Indianness. I so enjoyed the subversion of having such a familiar impact on Western audiences with such foreign processes, techniques, and materials. I felt I knew exactly how far I could push an exoticism before it became unrelatable; my code-switching, as big a burden as it had been in my childhood, had become an increasingly relied-upon superpower.

So what changed? Why, over the last decade, have I increasingly become able to be overtly Indian? Simple. America changed. The industry changed. Attitudes toward diversity changed. And global acceptance became a public relations good. Over the last ten years, my “secret” Indianness became an unfashionable and dated tool. In fact, it would impede my salability. It’s been strange to live in a world where diversity is prized by corporate institutions for fear of being branded irrelevant or having their stock prices plummet if they don’t have enough dark faces on their promotional materials, where it is demanded that I be more overt in my foreignness to sell my work through more succinct soundbites. Suddenly, it was cool to come out as an Indian. I had to fight decades of assimilative muscle memory to force myself to open up, to use the “brown flesh” crayon after being trained not to reach for it. But I’m slowly retuning my code-switching. My Indianness has become more and more overt in my life and work. I have written a South Asian script or two (though they too are global and multicultural rather than local in perspective). And three years ago, I took the job as Director of Education at EnActe Arts, a largely South Asian company. It was an association I would have avoided like the plague in my twenties for fear of being seen as not American enough to contribute to the mainstream machine.

But something as overtly Indian, to American eyes, as The Jungle Book? To attach myself to the very property I had avoided throughout my whole childhood? Phew. No wonder my stomach lurched when Vinita suggested it.

But an underlying irony of assimilation is that the materials of colonization are the same as those required for decolonization. Imperialist tactics and their psychological effects must be studied, deconstructed, and recontextualized. And The Jungle Book — in which Mowgli is pressured to choose fealty between two authentic sides of himself, written by another man for whom India was both a home and a burden — seemed an apt target. And if old rules were to be thrown out the window, what better way to do it than to have a writers’ room with so many young voices?

Decolonization through The Jungle Book

The Conservatory’s writers’ room happened over Zoom during the pandemic in summer of 2020. Two classroom teachers, Uma Sakhalkar and Vineet Gupta, ran the dramaturgical and narrative needs of each class (which, if you remember, consisted of mostly South Asian children and teenagers) and were responsible for producing the scenes through which the larger story would be told. My job was to visit the Zoom rooms every once in a while, ensuring that we were making progress, and ultimately, when handed all of the disparate scenes, to coalesce them into a well-structured final script. I was excited to work with such young voices, but soon realized the hilarity of attempting to apply structure to the ideas coming out of a writer’s room that consisted largely of children and teenagers.

Their daredevil ideas were off the wall and frequently led the classroom instructors down long, seemingly tangential rabbit holes. Hey, how about we add a peacock, since that’s so iconically Indian? Why did it make our primary antagonist less antagonist-y to provide him with a comic-relief jackal sidekick whose jokes blunted the impact of every threat he made? Shouldn’t Grey Brother have more to do? Why are the Monkey Pack treated so badly; shouldn’t we have a redemption arc for them as well? As much as I insisted that characters be cut so the story could be told cleanly (who needs Hathi? he doesn’t do anything, I told the classroom instructors once), the writers’ room responded with, “Well, you can’t cut the elephant. Or the snake. Or the jackal. Or the wolf brother. Or the wolf mother. Or the panther. Or the bear. Or the tigers. Or the monkeys. Or the kite. Or the bull. Or the humans. Or the newly minted peacock. Or the anyone. Or even this joke that I came up with.” Vinita herself called me once, saying, “I’ve had this growing instinct; I really feel like a wolf sister is threatening to be born.” I probably seemed overreactive with how quickly I snapped back in response, “No! No more new characters! There is no more room!” Conservation of character was not a narrative concept heavily respected in this writers’ room.

But I had to admit, even that was culturally authentic. How could South Asians talk about “belonging” if their family wasn’t absurdly large? How could it be authentically Indian with a small population? My recommendations of cutting each character, even the ones I considered minor, was a personal insult; in each repudiation, it was as if I could hear my mother saying, “Well, we can’t not invite your grandmother’s sister’s grandson’s wife to your wedding; she’s close family.” It was the first time in my life that it occurred to me that conservation of character was a uniquely Western narrative concept; the Mahabharata certainly didn’t follow that axiom. I worked to embrace the chaos. On the days when I visited the writing discussions in the Zoom classroom, I was struck by the bedlam of the overlapping chatter and excitement. Honestly, it was a jungle.

So if conservation of character was out, how could we bring structure to the madness? Well, then, I proposed to the classroom instructors, we needed a narrative frame. The solution was provided by Parker Downey, a writer friend of mine who was helping to corral ideas in the room. Parker suggested we start the play by having the newly minted character of Mayur the peacock upset with Rudyard Kipling for not including any of India’s national bird in The Jungle Book. This leads the on-stage Rudyard to ruefully admit that there are several glaring flaws with the story, and then the famous writer proceeds to bring the “correct” story to life before the audience’s eyes. This suggestion was hilarious to me; for so much of my life, Kipling had spoken for South Asians. Now, we’d get a chance to speak for him, put words in his mouth, dress him and present him however we liked. I also love the fact that a white American writer was the one who figured out how to best use the Indian peacock.

Now we had the frame by which we could “fix” the original story. Remember that Kipling falsely claimed in his book that Mowgli meant “frog”? This led me to include the following joke in the script.

Mayur and Rudy watch from stage left as center-stage, between all the animals of the jungle, Raksha the wolf holds her newly adopted son Baby Mowgli lovingly.

RAKSHA

I shall name him Mowgli...

for it means frog.

As Mayur interrupts from the side, Raksha and all the other animals freeze in place.

MAYUR

Ahem. Mowgli does not mean frog in any Indian language.

RUDY (startled)

It doesn’t? I could’ve sworn. Well, I can’t change it now!

It’s kind of iconic. Hmm. Let’s see...

He gestures to the main play, where the animals rewind and repeat the last moment.

RAKSHA

I shall name him Mowgli...

for it is a pleasant-sounding name.

The moment makes me laugh every time because of how frequently in my life the vast diaspora and diversity of Indian languages has been simplified into a meaningless single sonic unit. “Do you speak Indian?” I’ve been asked countless times by a well-meaning person with a complete ignorance toward South Asia’s complex ethnic and linguistic history. Therefore, I loved pointing out that Kipling chose Mowgli for no reason other than it sounded cute and exotic while not being too “foreign” and unrelatable. For someone who considers language to be the most insidious colonizing force (remember that to this day, India’s official government language is English), it was a joy to reclaim the words from a British man who played too fast and loose. Rann the kite was renamed Cheel, because Rann means “desert” and not “bird” (to be fair, Kipling corrected this mistake himself). Grey Brother was renamed “Burrabhai.” Authentic South Asian linguistic touches were peppered throughout the script (one line, “What am I, chopped liver?” became “What am I, tandoori chicken?”). Baloo was respelled Bhaalu. And my favorite little irony? Rudyard was renamed Rudy (not by me, but by the room), and I like to think it was chosen because it’s cute while not being too “foreign” and unrelatable. To my surprise, I loved how overt the choices were; there was no subversive Indianness here, and yet, I still knew it was a work that could succeed with Western audiences.

One of Vinita’s central concerns was how we handled the tiger Sher Khan, the vicious antagonist of the whole piece. Since tigers are currently being hunted to extinction, it seemed completely wrong that Mowgli end the piece by threatening Sher Khan with fire, i.e., imperializing the native with superior technology. India is also (again) going through rising Hindu-Muslim divisions as religious nationalism sweeps the subcontinent. When even a popular Bollywood actor like Aamir Khan is being boycotted for including a scene “poking fun” at religious zealotry in his last movie, it seemed obtuse to use the name “Khan” to describe the tiger. Instead, we used Bhaag (meaning “tiger”), and while he remained as traumatized by man’s treatment of him and his kin as any previous version, we made sure that by the end of the adaptation, he was rewarded for his guardianship over the jungle with an ability to contribute to self-rule. Vinita even eventually directed him to be more like an Indian maharaja in pre-Partition times, neutered under British colonial control and seeking to have some semblance of the power that he had once enjoyed before the advent of the outsiders. It was not a characterization I would have thought of myself — it was no longer solely trauma that drove the tiger’s anger, but a rightful loss of control over his own land.

For me, one of the most crucial pieces of the puzzle was Kaa the snake. While frequently depicted as a python, many of us thought at once she should be a cobra, so iconic in Hindu mythology and religion. (Kipling himself made cobras famous in his short story Rikki Tikki Tavi, in which a loyal mongoose defends a British family from the “invading” local snakes.) To make Kaa integral to the plot, I made her the Law of the Jungle itself, guiding the story to its eventual conclusion from an all-knowing and even terrifying place, much like Krishna in The Mahabharata. She is the only one to recognize that Mowgli is not “broken” or a JBCD (Jungle Born Confused Desi), but actually the hope for universality and peaceful coexistence. Yes, Kaa can be terrifying (just like Krishna during his Vishvarupa or frankly, during the entirety of “The Bhagavad-Gita”), but she also understands that Mowgli’s growth in the jungle and return to the village foments the thesis of the entire production: those individuals who are fully multicultured are the key to global coexistence. Code-switching is a heavy burden, yes, but it also builds an individual’s ability to recognize and navigate all the nuances of contrasting schema. Kaa knows that those who can code-switch have a superpower, not a handicap. After all, what is code-switching if not bilingualism in every form of language, from vocabulary to body to humor to behavior to social norm? Therefore, if linguistics is the insidious tool of colonization, it must also be the material tool of decolonization. And so Kaa, from a near-godly place, helps Mowgli recognize his position as the conduit between both worlds, comfortable in each, belonging to neither and both.

I found great humor in the process of working with a roomful of mostly South Asians, supplemented by open-minded and creative white and non-South Asian voices. When the scenes developed in Conservatory were finally given to me, they were an eclectic jumble of discordant voice, and somehow, I had to put it all together into a cohesive narrative. I found, to my great surprise, that it wasn’t even that hard. Knowing both Western and East Asian storytelling techniques, I found more than enough in my toolbox to ensure that each piece had a place. My greatest challenge was keeping the diverse voices alive on the page, to preserve as many jokes and as much dialogue as I could. Sure, there are so many characters that we sometimes had to break the cardinal rule of show-don’t-tell to ensure adequate exposition, and perhaps strictly speaking, from a Western narrative perspective, not every animal needed its story paid off… But as I turned a series of eclectic scenes into a full manuscript, I found that the key to my own decolonization was found in the satisfying intersection between reckless, childlike rule-breaking and intentional, measured thematic; I had to let go and trust in my own ability to code-switch, to reconcile the two worlds from which I am descended.

The premiere

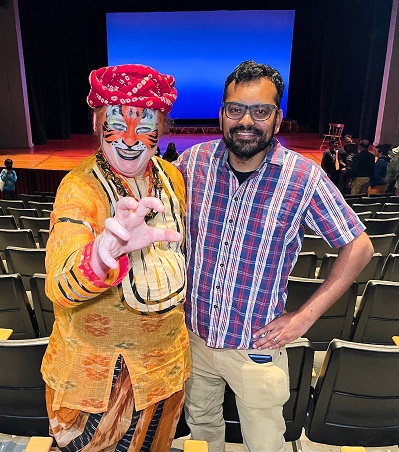

After the Covid pandemic had settled enough, the play began a national tour with a premiere in Palo Alto, California, in early October 2022. In the interim, I had moved out of state and largely handed over my duties as Director of Education at EnActe. To be honest, I had not thought that much about the play in the year before its premiere. I’d been too busy with big goings-on in my own life. But when I traveled back to California and watched the final rehearsal and several of the performances, I was struck by how strange it was to feel so connected to the South Asian community, to be a part of something that I had resisted overt association with for so long. Hundreds of choices had been made by a diverse cast, and by Vinita as director and Noah Luce as associate director. The spectacle of the costumes and the make-up and the projections and the sound and the lighting were details that, for once, I could appreciate as audience more than as creator. I noted with a smile that both the Indian tiger Sher Bhaag and the Indian peacock Mayur were played by white males (Karsten Freeman and Brady Voss), and they were nailing it. Intending to make something more authentically South Asian, we had ended up creating something more global. The show itself had not an Indian footprint but an individually multicultural one.

Sure, every show has its flaws, the kind of technical and creative missteps that happen during every live performance, but I did not notice these as much. It was a family show — and most of the themes about which I tend to write are decidedly for more mature audiences — but I didn’t mind that, either. If anything, watching the show, I just felt like the kid reading The Panchatantra and Amar Chitra Katha comics, belonging in that world as much as I did in my American other.

Conclusion

This is not to say that everything I write from now on will be South Asian-themed. And my decolonization is certainly not complete; there will be years more of epiphanies and choices and growth as I better and better navigate these two concordant sides of my identity. I will likely continue to be subversive rather than overt in my own work, but I hope to more frequently exercise that as choice rather than necessity.

“Write what you know,” a screenwriting professor once told me, and I was offended because what he really meant was, “Write what I think you know.”

I reacted by writing only the parts of me that he did not think I had the right to. In other words, for too many years, I openly wrote only half of what I knew, and smuggled the rest in as best as I could. But now, even if it’s only for their own capitalistic benefit, institutional gate-keepers are desperately seeking diversity. It’s taking me a long time to shake off my wariness and truly believe that my access to all the culture to which I have a right will not be limited if I indulge them. If I write and sell one South Asian script, will Hollywood studios not want to buy anything that isn’t? If I allow myself to say out loud, “I am Indian,” rather than hearing an awkward silence and laughter, will I hear only empty plaudits and snaps rather than a meaningful engagement with the content of my thought? After all, the lesson I knew even as a child is that diversity means nothing if it’s only skin deep. So I worry that if I forego subversion for overtness, then I will be not a man, but a mascot.

Decolonization does not happen in one moment; it is a process, taking years of realizations and efforts to implement them. Have I had my ultimate assimilative epiphany or is it still to come? I don’t know. But I do know that if my self-colonization was a coping mechanism in response to betrayals of my personhood, then the materials of my decolonization must be akin to the psychological processes of an individual overcoming their trust issues. I must point out in this instance, though, that my trust issues are not only my psychological problem, but a literal one. When one remains in a relationship that marginalizes their voice, even by way of surface-level celebration and congratulations (another way of describing Kipling’s white man’s burden), then trust has been lost for a valid reason. The material of my decolonization, therefore, lies in others’ ability to accept and engage with me as a simultaneously familiar and foreign entity. This requires an intellectual cognitive dissonance of the kind I am still not certain the larger world is capable.

That said, I genuinely loved watching the premiere of The Jungle Book and being, for a moment in my life, unsubtly Indian. And we all have to celebrate the wins where we find them, the times when our risks are rewarded by having our ideas engaged with. If division manifests through a history of segregated pain, then unity requires a history of shared joy. It’s important to note these moments when they happen.

It’s the only way I can turn my darkened eyes for a while to the light.

When young lips have drunk deep of the bitter waters of hate, suspicion, and despair, all the love in the world will not wholly take away that knowledge. It may only turn darkened eyes for a while to the light, and teach faith where no faith was.

RUDYARD KIPLING

All photography of EnActe Arts’ The Jungle Book show by Trisha Leeper.

Thank you so much for sharing this! So well-spoken and so vulnerable. It really helped me think of my own “decolonization” in a different way