A chance encounter

Picture this scene. You’re in the hippest coffee shop downtown that makes the best drinks around. Aromas of beans from around the world and low murmurs of conversation accented by clinks of cups and saucers envelop you as you approach the counter. Feeling bold, you order the newest roast and carry your cup to a nearby table, the warmth of the late-November sun welcoming your gentle first sips. As you sink deeper into your plush winged-back chair, the faint sounds of musicians tuning emerge from behind the high back of your seat. You look up, curious to see what’s going on as the owner of the coffee shop steps up to announce a special premiere by a local band and the ensemble leader then launches into the music. You never realized there was live music at this place — especially by up-and-coming musicians in the area — and you eagerly await its unfolding amidst the bustle of the café.

Do you have a vivid image in your mind?

You may have imagined something like this: a chic bohemian coffee lounge packed with bustling students chatting and clicking away on their laptops, nestled in for the end-of-semester push. The ensemble might have been a local indie-folk group that’s getting ready to drop a new LP. A scene of the modern bourgeois-meets-bohemian, yes?

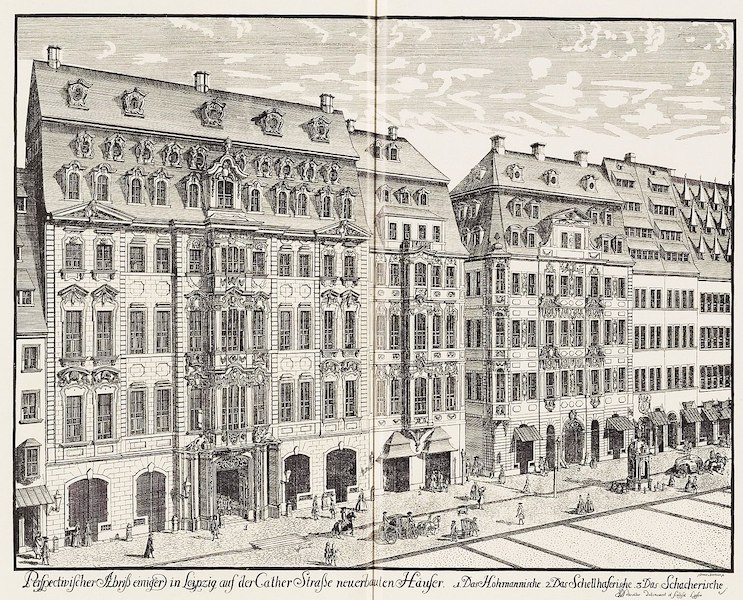

What if I told you the year was 1732, not 2022, and we were not just in a trendy area of town but in the Café Zimmermann in Leipzig? What if the ensemble was the Collegium Musicum (led by Johann Sebastian Bach) premiering his brand-new cantata Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht? (aka The Coffee Cantata — a miniature comic opera work that satirized the coffee craze that took over Leipzig); Collegium Musicum was known as the regular “house band” of Café Zimmermann and premiered many new works there. Though the imagined scene is fictionalized, the time, place, performers, and composition are not.[1]

It is remarkable that, as trend-engaged as we are, artists often recycle (or perhaps up-cycle?) ideas from the past and filter them through the lens of our current environment. In his book Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi comments on how creative people, regardless of expertise, must first be immersed in their established domain as a prerequisite to cultivating original ideas; the adage “one must learn the rules to break them” rings true. Establishing this framework then allows for a trackable departure from the known to the new via creative change. I believe creative thinking and feeling stems from novel connections and evolution of existing ideas; immersion in the past is critical to establishing a framework in the first place and primes human ingenuity to make those novel connections. In this way, as we will see below, the “revolution” of concert presentation in nontraditional venues is actually past practice under new lights.

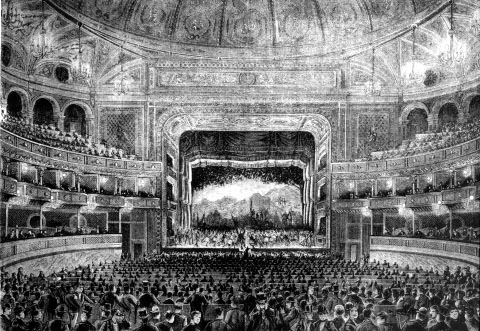

In some regards, the real revolution in concert presentation was housing performers in specialized venues tailored to the medium (the recital hall, the concert hall, the opera hall) — a revolution beginning in the Baroque, accelerating through the Enlightenment, becoming sacrosanct through Romanticism, and crystallizing in Modernity with expectations for audiences’ silent adoration of the composer and performer.[2] For centuries prior to specialized venues, Western art music lived in the nobility courts, churches, public forums, and gathering places of different classes, providing entertainment and functional service to the community. And even when specialized halls first opened, venues served primarily as places to see and be seen, with multiclass audiences dining and gossiping their way through the latest production or recital. Through the nineteenth century and beyond, concert halls became the norm for performing the classical canon. The avant-garde often sought refuge in academic settings away from the everyday gathering spots (cafes, bars, and clubs) that had become bastions of vernacular and popular culture. This relatively new separation of venue (some say “high-brow” vs. “low-brow”) is what initiatives like Classical Revolution, along with many others, seek to dismantle by bringing a diversity of repertoire and genres to venues outside the traditional concert halls.

Trendsetters

We have all come across articles and blogposts admonishing the decline and “graying” of classical music audiences.[3] Apparently, at some point in the late twentieth-century, those entering adulthood were not as interested as their parents’ generation was in classical music — the latest installment in the perpetual crisis of classical music in decline.[4] In the last two decades, there has been a bloom of new music organizations, as well as initiatives through existing organizations, focused on connecting to new audiences (typically the modern young-professional) through appealing to their trendy tastes and nightlife sensibilities. Here are a few global examples. The Night Shift concert series by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment brings Baroque and Classical era works to café and club venues, with an event from 2020 advertising: “Purcell with a pint? The Night Shift is classical music, minus the rules. Enjoy world-class musicians performing in a relaxed environment where you can enjoy a drink with the music.” Now I can drown my sorrows in hops with “Dido’s Lament” as the soundtrack. Great!

The organization Opera on Tap stemmed from performing aria selections at a bar in Brooklyn and since 2007 has grown to over twenty chapters, helping bring art song and opera scenes to bars, clubs, and even playgrounds. The Helix Collective represents classically trained performers that have created a genre-defying, multimedia ensemble that explores fusion of disparate styles in a variety of settings, self-described as “kick-ass classical.” Even the major orchestras are delving into this “getting out of the concert hall” trend. Just search “Happy-Hour” or “After-Hour”[5] concerts to find orchestras of all tiers presenting programs in more relaxed settings than the stuffy concert hall — often supplemented with a pricy drink menu. If you ever needed the answer to “does alcohol make things more fun?” these initiatives perhaps point to a resounding and boozy “yes.”

All joking aside, the prevalence of alcohol as a marketing strategy to attract young people perhaps makes assumptions about preferred nightlife experiences. Several recent studies have illustrated a reduction of alcohol consumption in young adults, showing that, of course, bars aren’t for everyone and we should perhaps expand our thinking on what constitutes nightlife, moving away from drinking as the focal point and to different experiences that are inclusive for those who do not consume alcohol.[6] Ideas could include hybridizing wellness (i.e., meditation/yoga) or experience-driven activities (i.e., painting, cooking/baking classes) during a performance. I’ll leave it to you to come up with more of your own.

Alcohol motivated or not, these initiatives strive to remove the barriers we’ve built over the centuries and return to our venue roots, inviting those with preconceived notions of the classical music experience to challenge their beliefs and see how this art form can be for everyone. This is where Classical Revolution comes in.

“Chamber Music for the People”

Classical Revolution started Fall 2006 in San Francisco with founder Charith Premawardhana initiating a weekly show at Revolution Café in the Mission District. The shows provided an outlet for local musicians to showcase their work as well as sight-read chamber music outside of traditional concert venues. The events quickly became popular, and Charith expanded to multiple venues and also began designing special projects. As of 2022, over 1,000 musicians have performed over 1,200 events in over 125 different venues in the Bay Area.[7] According to their website, Classical Revolution hosts three regular events in San Francisco: bi-monthly on Mondays at Revolution Café, weekly on Wednesdays at Monroe (an art deco lounge space), and the second Tuesday of each month at Caffe Trieste. Since its founding, dozens of Classical Revolution chapters have popped up in cities across North America and Europe (following the Opera on Tap model), ranging from major urban centers such as Chicago and Los Angeles to college towns like Ann Arbor. Each chapter has its own structure and focus, allowing for a decentralized collective that can tailor its chapters to the community and individual mission.

When I moved to Kansas City in Fall 2018 to begin work on a master’s degree, I learned about the Kansas City chapter and got involved. The previous organizers followed the gestalt of the San Francisco chapter, balancing “open mic” recurring events at local bar/café venues with occasional larger chamber projects. I took over the chapter that Fall, seeking to rebuild their structure. I recount my one-and-a-half-year tenure with Classical Revolution (cut short due to COVID-19) not to toot my own horn, but to share ideas that readers may find helpful. During my time, we were able to bring back the recurring “open mic” series with a local bar venue, providing an outlet for UMKC Conservatory students to workshop and perform repertoire outside of academic venues. We also worked with the UMKC Composer Guild to create a showcase concert for their members at our go-to venue and instituted a chamber music night at a local brewery that featured a string trio and wind nonet. Performers brought in a variety of styles, periods, and instrumentation (ranging from Steve Reich to Clara Schumann), creating a natural “variety show” within the open mic format. We also participated in a “porch series” that integrated chamber music in neighborhoods, including playing on people’s patios and even in a cemetery! I learned a lot about creating and promoting events, collaborating with performers, building audiences (especially outside of the Conservatory), and engaging with community venues. It was rewarding to meet audience members that said they would not have ever heard the variety of music we shared in our events, and it was surprising how many had some experience or background in music!

Part of the “revolution” in relation to audience is fostering approachability to instruments, genres, and styles that have been cloaked in “awe” and “mystery” since the Romantic era and then academicized since the twentieth century. To the “outsider” audience member with no “classical” music experience, there exists a stigma that one must have “training” to “understand” the music.[8] Listeners might fear that they can’t “get it” unless they’re already on the inside. As a classically trained musician, I empathize with that fear. During high school lunches, I would escape to the band room and listen to recordings with a couple of older friends (one of whom is currently a member of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra). That’s where I first heard Mahler, Bernstein, Respighi, and Tchaikovsky and fell in love with symphonic repertoire, but it’s also where I first encountered that feeling of being an outsider — “Wait, they heard a phrase I didn’t hear; are my ears terrible?” “How did they catch the return of that motive? Ugh, I’ll never be able to hear well!” were common thoughts of mine — and that was after years of piano lessons and performing in secondary school bands. Even today, those insecurities remain in my musical DNA. Yet time and time again, shifting listening to intuition and emotional responses reminds me of a vital purpose, and I have found that prefacing performances with this idea helps quell audience fears. Encourage the audience to listen with their hearts and guts, not just their heads — there isn’t a form and analysis quiz at the end of the performance! Listen with curiosity and exploration, not with the burden of deciphering if the technique and interpretation are “correct.” Reframing audience expectations in this way is equally important to providing nontraditional venues that create more informal spaces in which to engage with the music.

Full circle

Why does this work matter? What is the purpose of taking the time and energy to perform this music in “nontraditional” venues? In a practical sense, as repeated ad nauseum to the point of being a mantra, classical musicians in our time are expected to be entrepreneurial and build a diverse portfolio of performance, pedagogy, promotion, and engagement. Successful musicians are involved with a variety of projects and flexible skillsets applicable to many opportunities, often self-made ones. With nontraditional venue models, one can practice implementing these entrepreneurial skills through engaging diverse audiences in assorted venues. Yet beyond these pragmatic and career-oriented benefits, deeper social values are at play here as to why engaging in nontraditional programming and venues is important.

Bringing classical music outside the concert hall is one solution for accessibility and can aid in erasing pre-conceived assumptions of classical music as elitist, tied to socioeconomic status. People love it when a local artist displays their work at a coffee shop, a poetry reading session happens at a wine bar, or dancers move through the tables at a restaurant (as Fiddler’s Hearth in South Bend does on First Fridays!). That’s not to say everyone who serendipitously encounters live classical music will stop to listen deeply, but at least the sounds are traveling outside of enclaves that sometimes are better echo chambers than concert halls, where we wind up performing only for ourselves and the “insider” audience. Granted, I do enjoy going to a world-class concert hall and following those Romantic ideals of silent reverence for the performers and the music — I believe this experience can be for anyone and everyone, and it’s incumbent on arts organizations to eliminate barriers of entry. In fact, several studies point toward growing interest among Millennial and Gen-Z audiences in listening to classical music on streaming services.[9] This bodes well for a growing interest in live performances, and Classical Revolution can help build that interest.

Regular events at consistent spaces help build community — going to a café one Tuesday a month for a night of chamber music might become someone’s “thing to do.” Once a few people attend on a regular basis, a community’s nucleus forms as connections are created between regulars. Then the motivation to attend stems in part from the desire to be together with members of this specific community. In this way, emphasizing recurring events and nurturing social connections within the audience drives community building. That said, in performing in venues such as cafés, bars, and restaurants, a financial pitfall remains, such as means for getting to the venue, purchasing food and beverage, perhaps paying a cover, among other privileges. To avoid this, and to incorporate a stronger outreach component, we could consider different access points to connect with other more marginalized communities in places like nursing homes, hospitals, or prisons. My friend Drake Driscoll co-founded The VISION Collective to connect with immigrant and refugee communities in the United States. Growing interest in classical music does and continues to go hand-in-hand with advocacy and social justice. This topic itself needs its own article(s) to expand upon! The secret to all of this: there is no perfect substitute for the in-person experience. There have been and will be mountains of critique regarding humanity’s crash course in the virtual world circa March 2020, and those digital connection resources continue to be valuable in building connections. Yet I believe even the best VR headset and highest-fidelity sound equipment with lossless digital audio will never surpass the ineffable experience of in-person music-making. I believe Classical Revolution is not seeking to do away with existing modes of experiencing classical music — it’s broadening our understanding of both venue and audience, bringing the music to where the people are, just as other modern/popular/relevant visual and performing arts do. Will everyone in a public space pay attention or contribute to a tip jar? Certainly not! Yet there might be one person or child who does perk up and become interested in or curious about the music, for whom that chance encounter is pivotal.

In many ways, Classical Revolution is not revolutionary at all. Chamber music historically functioned as background entertainment music for social events, with concertized chamber music being a relatively newer genre in the scope of Western music history. Creating opportunities for musicians to perform contemporary music, comingled with historical and global styles in trendy gathering spaces, continues to demystify the genre to a wider audience and break down social and cultural barriers that perpetuate classical music’s identity as elitist or ivory tower.[10] As I’ve already mentioned, finding ways to help audiences connect on personal and emotional levels with the music is key — no one needs specialized training or knowledge to appreciate how music can move them.

We are arriving full circle at how venues can be used to connect with audiences; getting out of the halls has staying power. Just as Café Zimmerman was the mainstream venue of its time for local ensembles, and concert halls used to be the places “to be seen,” Classical Revolution seeks to bring classical music (back) to the popular venues of our time. Through the examples above and organizations like Classical Revolution, there are numerous new and existing opportunities. Perhaps you already have performed in nontraditional venues before and continue to do so — keep it up! Maybe there are organizations in your area that already have these kinds of events and you can get involved. If not, and if you haven’t considered such ventures before, here are some ways to get started.

Connect with local venues about setting up a regular night for classical music — perhaps you start with once or twice a month on a weeknight. Contact musician friends and setup an “open mic” format that is low-key and offers musical variety. Start advertising and building buzz in the community from there. It will take a series of events to build momentum, but trust that a regular schedule of events will slowly get things rolling. Setting up an organization and developing a mission/vision statement provides a guiding rudder for embarking on a course of action and building longevity. Get friends involved in planning the events! If you want to go the route of Classical Revolution, setting up a chapter is easy. Reach out to Charith to get the process started. You may also be surprised to find there is already a chapter in your area.

I believe part of the beauty of art is its recycling of ideas. Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp writes about how all art is essentially based in metaphor, and metaphors are based on association with memories.[11] As musicians, our memory is aural, passed down through formal study, recordings, and performance. Yet we forget ways of the past and at times unknowingly return to them, thinking the idea is purely novel without recognizing its historical roots. Perhaps it should be called Classical Renewal, a return to our venue roots. As practitioners of Western art music, let’s continue to engage in our communities and connect with new audiences to share our art in ingenious and accessible ways. If we believe classical music is for everyone, then we must be willing to try performing it everywhere and at every time. There is a time and place for the concert hall, but that must be part of a bigger artistic philosophy involving a myriad of venues, outreach, and initiatives, which as illustrated above, is already well under way as a movement. If you haven’t given it a try, I challenge you by year’s end to give at least one performance outside a traditional concert hall. And if you are already doing it — never stop.

[1] You can learn more about Bach’s infamous Coffee Cantata here.

[2] Alex Ross has a wonderful article from 2008 about the development of classical concerts.

[3] Lara Ehrlich’s 2019 article is particularly insightful on the decline of classical music audiences.

[4] Celeste Oram has a thought-provoking piece on the perpetual-crisis of classical music’s decline.

[5] A Happy-Hour example and an After-Hour example.

[6] Articles here, here, and here.

[7] Learn more about Classical Revolution here.

[8] Anthony Tommasini has a great article on listening to classical music for beginners.

[9] Articles on Millennial and Gen-Z classical music listening habits here and here.

[10] Here I am referring to the late Renaissance through early Modern eras since that repertoire constitutes most performances by classical musicians as an aggregate.

[11] A paraphrase from her amazing book The Creative Habit.