Last year (2021), I had the great honor of being invited by Grace Kweon and Brian V. Sengdala to talk with Asian Americans about Asian America, an opportunity I would rarely pass up. They invited me to join together with a group of scholars for a roundtable at the annual meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM). The exchanges with Grace, Brian, and our co-participants Nadia Chana, Yun Emily Wang, and Ameera Nimjee to prepare for our roundtable “Caring for Asian America in Ethnomusicology” were a model for care that I learned so much from and hope to continue to contribute to. The original framing question, or questions, of: What does it means to care for/about/through Asian America/Americans in the Society for Ethnomusicology? were at once particular to that meeting and that specific moment; yet, the reflections, intentions, and inspirations extend beyond that meeting, academic society, or 2021.

Dani Nutting and Elisa Moles founded The Collective in 2021 out of their “dissatisfaction with systemic dysfunction and with the shortcomings in both institutional and individual responses to broad societal issues,” and I share my reflections here in response to their call for change: “we need a revolution in form…we must be agents of change, working together to reimagine the structure and character of our field by critically engaging its history, its global essence and its changing position in society.” My thoughts here are drawn from the remarks I put together for the 2021 roundtable, but I share here now beyond 2021, and beyond an academic society’s annual meeting. Simultaneously hyper visible and invisible, caring for/about/through Asian America/Americans in 2022 is an ongoing commitment, taking some all too familiar and well-worn paths while also facing new challenges and/or new variations of longstanding challenges.

On institutions

As a multiracial Asian American woman in my late forties, my encounters with racism and sexism in the academy and in the workplace are, by now, not all too surprising.[1] To be sure, some are more rattling than others, and some are truly traumatic; some are unexpected, whereas others are entirely predictable. For me, after accumulating more strategies for navigating, interrupting, and surviving these incidents in my thirties, I’ve turned my attention in my forties to the responses to racist and sexist incidents. Often this involves a lack of response (including visibility, or erasure) as well as resistance.

As an Asian American scholar trained first in East Asian studies and ethnomusicology, later in social justice education pedagogy, and more recently engaging within Asian American studies, the roots of justice that form both Asian American studies and social justice education pedagogy have been a lifeline for me, especially in what I suppose I’ll loosely refer to as a middle phase of my career. The Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM) was a vital site for my graduate studies and early career, and I benefited tremendously from the scholarly engagement, mentoring, and professional development that reached far beyond the campus and community of my home institution. At my first academic conference, I met Tomie Hahn, Deborah Wong, and Su Zheng. My first major conference presentation two years later was chaired by Susan Asai. My engagement with SEM and its members is intertwined with my development as a scholar, a professional, and an individual. As a faculty member at small liberal arts colleges, mentoring and advising are central to my work with undergraduate students and new faculty on my campus. And the academic society has been an important site for me to connect with graduate students and junior faculty to mentor and provide support beyond my own campus.

I have made efforts to contribute, and at multiple times lead, from within the institution of my primary academic society to create a more inclusive space for BIPOC members and, more recently, a more accountable space for all our members. I have tried to be a part of conversations to center the needs and work of BIPOC members. However, as the years have gone by, I have shifted from attending -> to participating -> to leading -> to retreating -> to now cautiously returning.

Feminist writer and independent scholar Sara Ahmed opens her most recent book stating, “To be heard as complaining is not to be heard. To hear someone as complaining is an effective way of dismissing someone.”[2] Her book Complaint! is an attempt to counter this history…to “give room” and “to listen.”[3] Part of my commitment to care is to listen and to give space. Ahmed writes, “To refuse what has come to be is to fight to be.”[4] So how might we give room, listen, and fight to be….and how might we do this together? To be clear, the “we” I refer to here is for self-identifying Asian Americans. Yet I hope this doesn’t result in all the readers who do not self-identify as Asian American to stop reading. Quite the contrary, I intentionally share the thoughts here with a much broader audience in hopes of increasing visibility, informing, and sharing with our allies and members of our shared communities the work that I am calling for.

On Asian America

As many know, embody, and live…while others may be new to learning…Asian America as a movement and as an identity has always been fraught with a particular tension as a pan-ethnic group with disparate histories, cultures, political conflicts, and socioeconomic positioning within the United States and Canada. How do we, as Nadia Chana shares, “hold several understandings at once”[5] for the term without attempting to resolve it? As Josephine Nock-Hee Park writes in the context of Asian American studies, ethnic studies, and institutionalization: “I want to register the continued seeding of radical possibility alongside its simultaneous cooptation, but not as an attempt at a silver lining or even as a critique of the terms of success—but in the interest of successful redistribution to secure and expand the institutional space of ethnic studies.”[6] Park addresses the emergence of Asian American studies in the 1960s and how multicultural and neoliberal developments in following decades shifted the landscape of Asian American movements, writing: “…despite the real differences between then and now, the 1990s heyday of ethnic studies was achieved by savvy institutional agents who did not (only) see their integrating and strategic efforts as compromises with a corporatizing system; instead, they demystified institutional structures to fit themselves within the core.”[7]

For me, Asian America as a political and lived identity is something that has the potential to tie us together. Of course, there’s the shared gaze upon us from the other (that’s right. The other other). But in my mind what can tie us together…without a prerequisite flattening or erasing…is the political identity and the act of being/becoming Asian American. A racial consciousness, as Grace Kweon examines in her work, that is a call from Asian American activists before us here today.[8]

In spring 2022, The Journal of Asian American Studies published a special issue, “Reckoning with the Interdiscipline,” in which the editors explain: “…by acknowledging the significance of ‘reckoning’ vis-à-vis Asian American studies as a distinct interdiscipline, this special issue considers the ways in which the field has and has not lived up to its founding activist engagements and progressive promises. To wit, while Asian American studies incontrovertibly came of age as a recognizable institutional site within the US academy, its status as a legible political project is decidedly less certain.”[9] This reminds me of a pre-pandemic gathering on my campus where I had a wonderful conversation with a student about shared interests, including arts, activism, music, performance, you name it. I encouraged the student to take my course, “Taiko & Asian American Experiences,” to which the student responded, “Yeah, it looked really interesting, but I don’t identify as Asian American, I mean, what does that even mean?” The student continued on to share how they rejected the term, finding it to be both reductive and of no use. Of course, I wish the student had enrolled in the class so we could have had a fuller discussion, including the student’s rejection of the term — as Ameera Nimjee shares: to disassemble and then reassemble the term together.[10]

I feel fortunate to have found myself next to the same student some years later at another gathering on campus. We had a brief exchange in which the student shared with me how they had continued to wrestle with the term, identity, and discipline of Asian American studies since our last meeting — that the term still troubled them, but they now saw some potential and hope, together with the imperfections of coming together in such a way, and perhaps now they would consider taking the course.

In a recent article “49 Days of Mourning for George Floyd: An Asian American Re-awakening in St. Paul,” Karín Aguilar-San Juan writes, “Asian America is Dead, Long Live Asian America!”[11] The tension with the term is ongoing yet we keep coming back to it. The Asian American Movement, or what Yellow Horse & Nakagawa and Chan refer to as the “project of Asian America,”[12] has a potential that needs the buy in, the tie in, the commitment, in order to be activated. Even as a disparate group within the discipline of ethnomusicology and within an academic society such as SEM (as one example), I know that individual and collective commitments have resulted in moments of transformation and care. Though the moments are fewer than we may hope, they are there. And I wonder what futures are possible with an increased and intentional commitment amongst Asian Americans to the project of Asian America?

Back to institutions

As I’ve shared, my engagement with my primary academic society (as just one example of various institutional relationships) has shifted throughout various times. In full transparency, during times of recent leadership I thought deeply, at multiple points, about resigning and breaking away from the harm of institutions. But I made decisions to stay in my elected positions in hopes of continuing to work alongside colleagues and to see through the positions I stepped up to hold; however, as I rotated out of leadership positions I really stepped back, to retreat, to take a breath, to disengage; and also to listen more and to learn more about who needs what and why…a retreat but not a resignation… and then Yun Emily Wang’s roundtable contributions[13] got me thinking about surrendering to receive strength…it was in this stepping back that I questioned whether or how I might return…I digress…

Perhaps exactly because I have had so many vibrant and meaningful engagements with and within my primary academic society is precisely why the encounters with racism and sexism there often take such a heavy toll. As an Asian American woman, I’ve been asked “YOU count?” (with horror and disgust) when sharing that I received a diversity fellowship. Only to turn around in another scenario to the comment “not YOU!” when interrupting an anti-Asian racist and xenophobic comment because the speaker could not hold Asian and American together in one body (so somehow, I wasn’t meant to take offense at the Asian slur because I was born and raised in the United States?). I share examples of brief encounters from professional meetings here publicly that I typically share privately to dig into the moments that I observe/witness/experience in professional contexts, here SEM — a moment of reckoning with the colonial foundations of our discipline and long overdue acknowledgement — and understanding — of how racism, sexism, and other systems of oppression function at the micro and macro levels of such academic societies.

I keep returning to my Swarthmore colleague Edwin Mayorga’s article “Burn it Down: The Incommensurability of the University and Decolonization,”[14] a project he co-authored with two former students Lekey Leidecker & Daniel Orr de Gutierrez. They write, “The university cannot be a vehicle for decolonization as long as it is defined by [this] coloniality, because the agendas of the two are incommensurable… Thus, we argue, that the university cannot be decolonized. It cannot be salvaged. It must be incinerated.”[15] I am writing elsewhere about how and why we may want to burn it all down.[16] And if not, what are alternatives? One short version for now is that I personally don’t necessarily think we need to burn it all down. But I am drawn to learn more as I hear increasing calls for doing so. The critique of what is and isn’t possible…and scrutinizing competing agendas…and I find hope and inspiration in the suggestions that Mayorga et al. land on. Ultimately, the questions they leave us with are, “How might we outlast the systems by focusing on what we need to survive, what we need for empowerment, and finally, to take what we need from the existing systems?”[17] How can we take care of one another (survive), support one another (empowerment), and what do we want to salvage from current practices (theft by conversion) in service of survival and empowerment?

I’ll fast forward to my rendering of their concluding three stances as a possible application to conversations of caring for Asian America/ns in institutional contexts such as an academic society. That is, three possible stances I’m directing to/for Asian Americans: survival, empowerment, and (theft by) conversion.[18] How, as Asian Americans in ethnomusicology (as one example), can we help ourselves and one another survive? How might we empower ourselves and each other? What role can we play as Asian Americans in redirecting and redistributing power and resources to our Indigenous, Native, and Black colleagues?

On block parties (and Asian Arts Initiative)

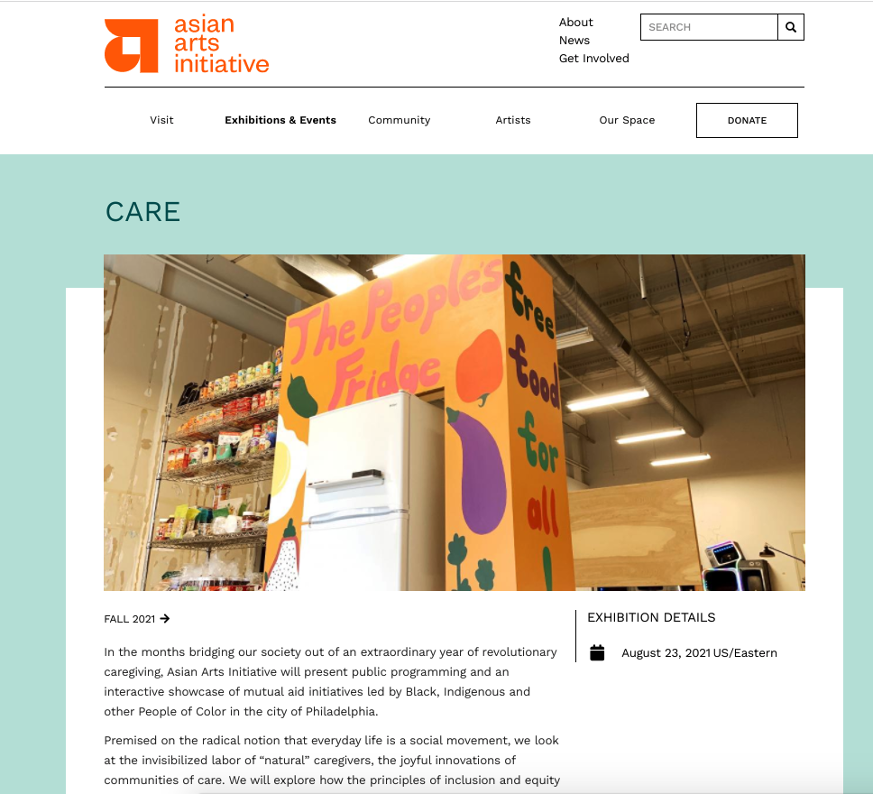

As the topic of care has emerged and reemerged…and then consumed my thoughts while preparing for the 2021 roundtable…I knew I wanted to bring the work of Asian Arts Initiative (AAI) to the conversation. I am a huge fan and admirer of AAI and feel so fortunate to have landed in the greater Philadelphia area in 2017 to get to know the organization that is based out of Philadelphia’s Chinatown. Upon arriving at my current institution, the names Gayle Isa and AAI came up in seemingly every other conversation. Once I got to know more about AAI, I could understand why. The work of this Asian American arts organization directly aligns with my own teaching and research commitments, and it’s been energizing to find ways to collaborate.

In fall 2021 I was on a panel with Anne Ishii, the current Executive Director of AAI. As we dug into the panel’s theme of Arts & Activism and community collaborations, Anne reminded me of the origins of AAI as an organization that emerged out of growing racial tensions between African American and Asian American communities. Gayle Isa founded AAI in 1993 as a site for cross-cultural understanding and community building through the arts after identifying a lack of spaces for Asian Americans.

Fast forward to the COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, racial reckonings across the US, and increased Anti-Asian violence. AAI has been responding to all of the above. In fall 2021, their featured exhibit was CARE, “public programming and an interactive showcase of mutual aid initiatives led by Black, Indigenous and other People of Color in the city of Philadelphia.” On a 2021 panel Anne talked about care as activism. Care as expressing needs. And care as offering support. She talked about how sometimes the need might not be obvious…or direct…or linear…it might be seemingly tangential but is so critically important for other work to be possible… For example, one need in the community AAI heard in 2020 was to provide safe space for childcare, and with internet access.

Imagine what needs are out there that we don’t yet see…needs that, once met, can provide new works, transformations, and leaders.

Another identified need was the opportunity to safely come together. AAI’s response: a Block Party! The event predates the pandemic yet was an important one to reconvene in 2021 after a pause in 2020. (The artwork included in this article is from artist Joshua Cochran who unveiled a new mural at the recent block party.)

AAI’s attention to care continues to inspire me, and I turn to their work as a model for care and Asian America/ns. Basic support of internet access and childcare were critical to the AAI community and neighborhood during 2020, and AAI listened, responded, and worked toward supporting the identified needs. SEM President Tomie Hahn’s recent year of “radical listening”[19] is another model for one way an institution can commit to listening in order to better understand and identify the needs of its members. Ultimately, how can increased attention to care, and to listening, help institutions and organizations do better in supporting their communities? To be sure, one institution cannot, nor should not, be expected to serve all the needs of their community. However, a commitment to caring for members of an institution surely requires knowledge of the challenges members are facing and the specific ways an institution is able to provide care in order for members to thrive.

As we all move through different institutions, be it as members and/or leaders, what might we activate and make possible when we ask the questions: Where are the spaces for Asian Americans in our institutions? How can we create more opportunities to meet each other? To listen to each other? Especially to better understand the non-linear, not-so-obvious, and indirect needs? How can we support each other in expressing our needs? How can we offer support? What can we take from existing institutions to not only survive but to truly thrive? And to close: when’s the next block party?!

[1] See On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Sara Ahmed 2012), Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia (Gutiérrez y Muhs, Niemann, González, and Harris 2012), and Presumed Incompetent II: Race, Class, Power, and Resistance of Women in Academia (Niemann, Gutiérrez Y Muhs and González, 2020) as some starting points for newcomers to the topic.

[2] Ahmed, Sara. Complaint! (NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 1.

[3] Ibid, 3.

[4] Ibid, 26.

[5] Chana, Nadia. 2021. “Caring for Asian America in Ethnomusicology.” Roundtable at Society for Ethnomusicology 2021 Annual Meeting, virtual, October 29, 2021.

[6] Park, Josephine Nock-Hee. “The Success of Asian American Studies.” Journal of Asian American Studies 25, no. 2 (2022): 188-189.

[7] Ibid, 189.

[8] Kweon, Grace. “Caring for Asian America in Ethnomusicology.” Roundtable at Society for Ethnomusicology 2021 Annual Meeting, virtual, October 29, 2021.

[9] Schlund-Vials, Cathy J., Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, and Paul Spickard. “The Why and Whither of Asian American Studies: Toward a Reckoning.” Journal of Asian American Studies 25, no. 2 (2022): viii.

[10] Nimjee, Ameera. “Caring for Asian America in Ethnomusicology.” Roundtable at Society for Ethnomusicology 2021 Annual Meeting, virtual, October 29, 2021.

[11] Aguilar-San Juan, Karín. “49 Days of Mourning for George Floyd: An Asian American Re-awakening in St. Paul.” Amerasia Journal 46, no. 3 (2021): 289.

[12] See Yellow Horse & Nakagawa (2020) and Chan (2000).

[13] Wang, Yun Emily. “Listening from the Bottom (as Care).” Roundtable at Society for Ethnomusicology 2021 Annual Meeting, virtual, October 29, 2021.

[14] Mayorga, Edwin, Lekey Leidecker, and Daniel Orr de Gutierrez. “Burn It Down: The Incommensurability of the University and Decolonization.” Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis 8, no. 1 (2019): 87–106.

[15] Ibid, 103.

[16] “Moments & Movements: Ducking & Diving” currently under review and based on lectures presented at UC Davis (2022) and National Taiwan University (2021).

[17] Mayorga, Leidecker and Orr de Guiterrez 2019, 103.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Hahn, Tomie. “Transparent Musings.” SEM (Society for Ethnomusicology) Newsletter 55, No. 2 (2021): 1, 3.