As a white woman from New England, I grew up learning and performing pieces by primarily white male composers. I believe this is not an uncommon experience. My own professional trajectory might have been less plagued by self-doubt if I had been taught more pieces by women and non-binary composers; and I might have been empowered to be a bolder musical explorer had I been taught more works by BIPOC composers. The work of many activists through many decades has finally brought me — a singer and conductor — and many other white musicians, to a point where we consciously acknowledge the need for diversity. It is a now popular topic for conference programming and (lest the Gentle Reader think I am not aware) articles and listicles such as this one. But in the Western art music field, this has not translated, for example, to an equal number of BIPOC musicians scaling the same professional heights as their white colleagues or to programming that is as diverse as our country.

Because my primary background is in performance, it has been daunting to formally step into the discussion around racism in music, but because that is exactly what I believe we should be doing, it would be hypocritical not to lead by example. My own research has been on the subject of Black American composers, so that is the topic I will focus on in this article. Whatever your background, I hope you will find inspiration and resources in this article to explore, enjoy, and perform the music of some stunningly talented composers that you may not have performed before. I believe that it is not only recommended for all musicians — especially those of us with more racial privilege — to program and perform works of BIPOC composers, but essential.

Institutional racism, the accretion of hundreds of years of prejudiced decisions that create a self-sustaining machinery of bias, cannot be dismantled by a few articles, conference workshops, and helpings of good intentions. White supremacy is baked into the very core of Western art music; it took a lot of time and effort and money to make that happen, and it will take a lot of time and effort and money to rectify it — to rebuild classical music into an institution that celebrates everybody and does not valorize only the work of the privileged. Before suggesting some works to explore, I want to delve into the reasons diversifying the canon has been so difficult and emphasize how important this diversification is despite its challenges.

Necessities and challenges of diverse programming

Repertoire is one aspect of classical music that requires serious expansion, and, as a conductor who loves programming, it is the aspect in which I am personally most interested. The works appearing on concerts of Western art music, ranging from the top orchestras in the world down to our local school programs, are still primarily by white — and primarily male — composers. We need to discuss why. Thoughtful programming is one way to make sure that our choices as conductors, teachers, students, and performers reflect the values we hold where diversity, equity, and inclusion are concerned. Meaning, if we truly reject the belief that white composers are inherently more talented than composers from other racial backgrounds (a racist and unacceptable belief), then we need to be sharing programs that are not entirely, or even mostly, written by white composers. (Other aspects of classical music that could also use expansion are access to education, training and instruments, and accessibility of performances, to name just a few.)

Any conductor looking at their ensemble’s library, or any private music teacher looking at the table of contents in their repertoire books, will know that the easiest path is to teach that with which you are familiar and which is easily available. When making programming choices, a single piece must meet many criteria, and when searching for the perfect piece to fill a niche in a concert, it is much easier to draw on one’s own experience. My own experience — and I am not alone — being taught pieces written by men, most of whom were white, means that those pieces are exactly the repertoire on the tip of my brain when I need to pull up the perfect piece that is three minutes long, in a language my ensemble can handle, will challenge them just enough, will let us work on solfege or triplets or breath support, and can fit into a program about nature or winter or celebration or remembrance. It is a challenge to find, instead, a piece that I do not already know, by a woman composer and/or a trans composer and/or someone who is Black or Chinese or Latinx or Indigenous or otherwise reflects the identity of one of my students who never gets to perform music by someone like them.

Despite these challenges, it is critical for all students and musicians of any age to feel a sense of belonging, and to know that people like them have a place within classical music. And it is equally important for musicians to experience the point of view of a composer who is unlike them in some way, to feel the sense of discovery and excitement that can bring. We cannot create a healthy musical society if some musicians only experience the one, and some musicians only the other.

It requires time-consuming research on my part, as a conductor, to find a piece that matches all the requirements I might have for my ensemble. I have to hunt around websites and listen to recordings and then either request perusal scores, buy single copies, or send composers and publishers e-mails and wait for a response. Once I have chosen a piece, I then have to dedicate time to learning a new work, which includes the historical context, the pronunciation, the notes, and all the other details that go into learning and teaching a piece of music. If the composer is drawing on a different musical background than my own, the piece might challenge me rhythmically, harmonically, structurally, or otherwise. After having spent my own money to get my hands on perusal scores, I have to find money in my school’s budget to buy enough copies of the piece for everyone. Sometimes the work is out of print, and then I need to jump through publisher hoops to get permission to copy it. Sometimes, as in the case of William Grant Still, I must get in touch with a composer’s relative who is single-handedly trying to run a publishing company.

I do not mean to frame this challenge as noble — this attempt to chip away at Mt. White Supremacy when programming the next semester’s concert. Nor do I wish to complain about the extra energy it takes to expand programming. I mean to confirm that it is occasionally nearly impossible, because time and money and energy are limited, and if you only programmed white male composers for your most recent concert, then it is not useful to wallow in guilt. If you really want to incorporate anti-racism into your musical lens and actions (and I strongly encourage you, Gentle Reader, to do so) then you must adopt a long-term actionable strategy. I think frequently of the famous quote by Rabbi Tarfon: “It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.” Finding rich repertoire by composers that ensembles and institutions and publishing houses have historically ignored is a lifelong process.

One note before we proceed with considering our 2022 programming: Racism makes everything not only deadly, unjust, and soul-crushing, but also awkward. So, let’s talk about it. And by “it,” I mean two topics: there is caution around programming Black composers, and there is a lack of enthusiasm. I will address caution first.

On caution and throwing it to the wind

A lot of non-Black conductors worry about “appropriation” when performing works by Black composers with their ensemble, especially if that ensemble does not include any Black students. (For any non-American readers, American society, particularly in the northeast, where I live, is still highly segregated.) When my non-Black colleagues discuss programming works by Black composers, I sense a wariness about being appropriative, or just “not doing it right” and subsequently being labeled racist.

It is true that in the current year of 2022, and with our current cultural tensions, there are indeed some works that speak particularly about the pain of the Black experience, which were sometimes intended by the composer for performance by a particular Black artist, and which should be left to Black performers. I can envision a future in which that is not true, but I believe it is true right now. More broadly, I believe that when performing works from idiomatic Black music genres, such as gospel and African American spirituals, conductors are responsible for communicating to both their musicians and their audiences the full meaning and context of those musics, and I highly recommend collaborating or consulting with Black artists in your city or state when performing those works. (This means: pay them money.)

But, overall, I find this caution around programming Black composers infuriating. Black artists are already carrying an extra burden on their shoulders. Black musicians are sometimes only asked to perform programs based on the Black experience, and not invited to conduct or perform major works by white composers. Black teachers and professors are asked to be on diversity committees; give DEI presentations; mentor BIPOC students; tiptoe around colleague, student, and parent feelings around race; and all this on top of a wage gap that the United States has still not been able to erase. With Black colleagues facing such substantial extra demands on their time and energy, white musicians cannot also ask them to take the lead on de-colonizing the canon! It is primarily the responsibility of non-Black musicians to do so, here and in the case of other minority groups.

This also means questioning the wisdom we have received through our musical lives about which works are great and which are lesser; asking ourselves why certain composers became and remained popular at certain periods of time; and researching the barriers to performance and publication that various composers faced in different times and places. Looking up the language that contemporaneous reviewers used about BIPOC composers is a great way to begin to understand why certain works never entered popular rotation. And finally, white musicians should take the lead in seeking out and programming works by BIPOC composers. A sense of reserve around doing so is unbecoming.[1]

In addition, non-Black musicians must rid ourselves of the subconscious assumption that any Black composer (and this goes for other under-represented groups as well) is ONLY ever writing about their identity as a BLACK person. Admittedly, it is true that in certain decades this became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Margaret Bonds, for example, sometimes struggled to interest publishers in anything that was not a Negro spiritual arrangement. Because she loved and treasured the Negro spiritual and was happy to contribute to its establishment in the concert hall as a respected musical style, she was proud of her work in this area. But it also meant that during her lifetime she could not get her Mass setting published; she could not get her Edna St. Vincent Millay art songs published; she could not get her church anthems published; she could not get someone to offer her an opera libretto to set; and on and on. Luckily many of her works have been published within the past year.

And this leads to the main point: even if you have to dig a little, there is an available wealth of music by Black composers about every conceivable topic that is expanding every day. The works of Bach and Mozart are considered “universal,” but they are no more universal than the works of Florence Price and Ulysses Kay. In addition to using repertoire by Black composers to explore certain topics (freedom, unity) or times of year (MLK Day, Black History Month), I encourage you to program a work by a Black composer that has nothing to do with their identity as a Black composer.

On enthusiasm and musical value

Having disposed of the need for caution, I must address the second, and very unfortunate, source of resistance I sometimes feel from my white colleagues around programming Black composers: the lack of enthusiasm for doing research and programming diverse works that I encounter is, I sadly believe, rooted in internalized sexism and racism. I sense it more strongly when discussing programming of non-male composers than I do when discussing non-white composers, though that is likely related to my own identity as a woman who is white. There is frequently an undercurrent to conversations where colleagues telegraph, “Well, I have to expand my programming because everyone is whining about diversity, but really, the stuff by women/BIPOC composers isn’t that great, so, what a chore to have to program it.” For my Black colleagues who have also experienced this undercurrent, I want to regretfully confirm that you are not imagining it. This kind of toxic mentality is something we all have a responsibility to root out and challenge, whether in ourselves or others.

The line of thinking seems to be that since certain groups were historically oppressed and did not create much material to begin with, then what we are left with is surely not as good. This is not true. There is plenty of repertoire; we just are not familiar with it. And it has been scientifically proven that the single most attractive quality in music is familiarity. The cultural narrative assigned every time someone programs a Beethoven symphony is that they are choosing value, when in fact they are choosing familiarity. It is true that there is a deep beauty within some Western art musical traditions that deserves to be carried forward. I have a precious memory of the hairs on my arms standing up when hearing a live performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in college. And I never tire of singing Handel’s Messiah and am looking forward to the time when I can conduct my own annual Messiah sing. I am not suggesting that the task of combining decades-long traditions with increasing canon diversity is an easy one. However, this integration of tradition and diversity lies at the heart of the task facing classical musicians today, and it must be undertaken.

While no one is obliged to be enamored of a given piece simply because of the identity of the composer, there is much fabulous music available from composers of all possible identities. The best music does not just happen to have been written by white male composers. I argue that if the best music that you personally know has been written by white male composers, then you were unjustly robbed during your education of learning about the full array of pieces and musics that you might have loved. Tangled up in these subjective evaluations are also beliefs about what constitutes “good” music — complexity, length, form, subject material, rhythmic variety, ensemble size, and overall musical style — leading to value judgements about what music is truly great. We should consider tearing down such value judgements — yet another philosophical gravitational field beyond the scope of this article.

Perhaps, however, as you consider expanding your programming, do not assume that a piece whose form is based on repeating interlocking patterns is more simplistic than a piece in sonata form; or that a piece based on the mambo or salsa is more shallow than a piece based on the chaconne or gigue; or that a piece about a subject matter historically associated with the feminine is less meaty than a piece about subject matter historically associated with the masculine; or that a piece written for a younger ensemble has nothing to offer your advanced ensemble. (For a wickedly difficult work written for youth chorus, check out Tania León’s Rimas Tropicales.)

The list

Finally, many composers want their music to be performed — by everybody! And that means not just once, but all the time. To quote Margaret Bonds in a letter to her friend Langston Hughes in 1960: “I’ll love it when more singers who are NOT Negroes recognize the universal message in our songs and sing them far and wide. It’s happening more and more.” Can you build one of the works listed below into your school, church, or ensemble traditions? Is there a piece you perform every year at certain celebrations? Could it be by a Black composer? The following list includes many links and resources to help you get a head start on researching and learning this repertoire, and on thinking about how to program these works in a curious, thoughtful, and critically informed way. Many of the names may be familiar to you, but you have never performed their music. This list will help you ensure that this is the year to perform some of these fabulous works!

Unless otherwise noted, all recommended works are available for listening on YouTube. The list is in chronological order. As a conductor, my recommended works are biased toward ensemble pieces.

Florence Price (1887-1953)

- Born and grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas

- Wrote for orchestra, piano solo, organ solo; some chorus and solo voice; larger works include four symphonies, one piano concerto, two violin concertos

- Style combines African American spirituals, church music, and other American styles with European Romanticism; can clearly hear the influence of the European symphonic tradition; lush color palette; often uses dance rhythms

- More information

- Works list

- Some works available on IMSLP, but the majority of the catalogue is at Wise Music Classical

Recommended Piece: Concerto in One Movement for piano

Available at Wise Music Classical site; suitable for skilled student orchestras; not too long (20 min) with manageable orchestration; many moods, including very jazzy

Recommended piece: Adoration for organ solo

Available for free on IMSLP; suitable for beginners, pedal work is straightforward, slow tempo, contemplative; at 3:30 is good for preludes, etc.

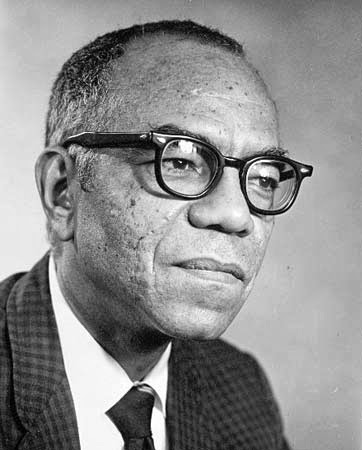

William Grant Still (1895-1978)

- Born in Woodville, Mississippi; grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas

- Wrote for chorus, orchestra, symphonic band, opera, most other genres; larger works include his opera Troubled Island, and his very famous Afro-American Symphony, which until 1950 was the most popular orchestral piece composed by an American

- Style similar to Price — combines influences of European classical music with African American melodies, harmonies, and rhythmic patterns — but can also hear a strong influence of movie music (Still composed and arranged music for multiple films)

- Most of his sheet music can be found at this website, operated by his family who are very responsive. Also, lots of background info on this site. Some pieces can be found at Presto Music or other publishers, but start here.

Recommended piece: Christmas in the Western World for choir

Available from Peer Music; multiple movements setting Christmas songs from the Americas; very accessible for school or church choirs; all ten movements are 20-25 minutes, but you can mix and match; for mixed chorus, piano, and string quartet or string orchestra

Recommended piece: Plain Chant for America for solo voice or SATB chorus; with piano or orchestra (very flexible)

Available at williamgrantstill.com; moving inspirational and anti-fascist poem by Katherine Chapin discusses various historical events of the 20th century; choral arrangement not difficult, but rhythm, cut-offs, and clean diction are important; work is slightly longer (8 minutes)

Margaret Bonds (1913-1972)

- Born and grew up in Chicago, Illinois

- Wrote for chorus, solo voice; some orchestra, solo piano, and theater music; larger works include cantatas Ballad of the Brown King and Simon Bore the Cross, Credo for chorus and orchestra; Montgomery Variations for orchestra

- Style often incorporates quotations from African American spirituals; puts a primary emphasis on melody, often with jazz-influenced harmonies underneath; musical personality often energetic and jaunty

- Biographical info

- Reasonably good works list

- Works available at various publishers, including Hildegard Publishing, Theodore Presser, and GIA

Recommended piece: The Negro Speaks of Rivers for solo voice or SATB chorus

Link to solo art song; Link to choral version; text by Langston Hughes; about 3 minutes long; straightforward SATB choral part that is strong and thrilling; very difficult piano part; also available as an art song (the original format)

Recommended piece: St. Francis’ Prayer for SATB chorus

Available from Hildegard Publishing; familiar text by St. Francis of Assisi; straightforward SATB choral part, good for church or school

Recommended piece: Credo for orchestra and chorus

Available from Hildegard Publishing; inspirational text by W.E.B. DuBois; multi-movement, approx. 30-40 minutes; Bonds does not call this an oratorio, but the term is appropriate; for SATB chorus, soprano and baritone solos, and orchestra; large orchestration requires resources; SATB writing is meaty but not overly challenging; suitable for large amateur choirs, college choirs

Ulysses Kay (1917-1995)

- Born and grew up in Tuscon, Arizona

- Wrote many works for orchestra; overall dizzying output for all combinations and ensembles; wrote five operas, including Jubilee and Frederick Douglass; other larger works include Chariots and Concerto for Orchestra for orchestra

- Style is neo-Classical (studied with Hindemith); tends to be crisp and clean; emphasis on structure and form

- Works list and biography can be found at the extraordinary site AfriClassical.com, which is a labor of love spearheaded by a retired judge from Michigan, and which is home to some of the most complete works lists and biographies available for many Black composers

- For scores, start at Carl Fischer; but Kay’s work is the most difficult to track down of any on this list. I wanted to recommend Six Dances for String Orchestra, which I find charming and accessible, but could not find rental parts online. The work was recorded, so following up with that orchestra may yield results. Works by Kay that are recorded do not have easily available scores and vice versa. This is an example of how further research and advocacy is needed for those composers on this list not still living.

Recommended piece: String Triptych for string orchestra

Rental parts and score available from Carl Fischer; composed for the Missouri All State High School String Orchestra; three contrasting movements; could not find recording online

Recommended piece: Prelude for Solo Flute

Available from Carl Fischer; for advanced students who need a challenge and teachers tired of hearing Syrinx; 3 minutes

George Walker (1922-2018)

- Born and grew up in Washington, D.C.

- Wrote for all instruments and ensembles, including concertos for piano, violin, trombone, and cello; many orchestra works; and chamber music for many combinations; larger works include Lilacs, for voice and orchestra, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1996

- Possibly the most variable style of any composer on this list; different works may include styles such as neo-Romantic, serialist, or popular music

- Walker died in 2018, but it appears his website is still available

- Complete works list not available online, but selected works lists available at Oxford Music Online, Wikipedia, and AfriClassical.com; works list of available scores at Keiser Southern Music

Recommended piece: Icarus in Orbit for full or chamber orchestra

Available at Keiser Southern Music; commissioned by the New Jersey Youth Symphony; sinister, eerie, and dramatic; introduce your ensemble and audience to denser harmonic language in a short work (7 minutes long)

Recommended piece: Lyric for Strings for string orchestra; also a version for young orchestras

Available at Keiser Southern Music; based on the second movement of his String Quartet No. 1; 6-7 minutes long, very lush, neo-Romantic, tuneful; not too challenging and one of his more popular works

Recommended piece: Three Songs for high voice and piano

Available at Keiser Southern Music; simple, accessible, not too challenging with notes or rhythms; sets three poems: I. “In Time of Silver Rain” (Langston Hughes), II. “I Never Saw a Moor” (Emily Dickinson), III. “Mother Goose- ca 2054” (Irene Sekula); final song is very funny!

Adolphus Hailstork (b. 1941)

- Born in Rochester, New York; grew up in Albany, New York

- Writes for orchestra, piano, choral; some chamber; larger works include I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes (cantata for tenor solo, chorus and orchestra), 7 Songs of the Rubaiyat, and multiple symphonies

- Style is neo-Romantic and builds on African American styles; tendency toward longer melodic lines, dense texture, and lush, sweeping phrases

- Bio and works list at adolphushailstork.com

- Most works published by Theodore Presser

Recommended piece: Celebration for Concert Band

Available at Theodore Presser; exuberant, short burst of energy in 3 minutes; very useful for school events

Recommended piece: I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes for SATB chorus, tenor solo, and orchestra

Available at Theodore Presser; 20-minute cantata on text of Psalm 121; dedicated to the memory of Undine Smith Moore; would pair very well with her 40-minute oratorio Scenes from the Life of a Martyr for a nice meaty program; lush work suitable for college choirs or oratorio societies

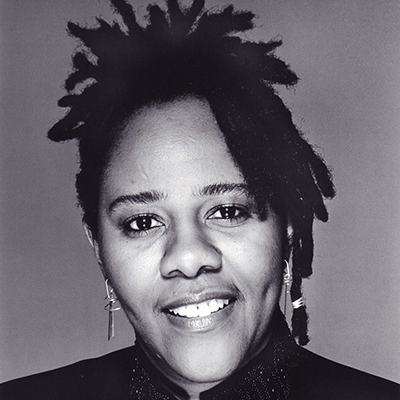

Tania León (b. 1943)

- Born and grew up in Havana, Cuba

- Writes for orchestra, chorus, wind ensemble and band, ballet, chamber, piano, vocal solo; some other works for solo instruments, one opera

- Primary stylistic influence is Latin American; early work has twelve-tone influences; rhythmically complex and dynamic; frequent use of percussion; extremely varied use of tonal color

- Biography and works list at tanialeon.com

- Peer Music has some of her works published; for others you must reach out to her staff directly.

Recommended piece: Stride for orchestra

Available at Peer Music; co-commissioned and premiered by the New York Philharmonic; won the Pulitzer Prize in Music in 2021; 15 minutes, very challenging

Recommended piece: El Manisero (“The Peanut-Vendor”) for mixed chorus a cappella

Available at Peer Music; commissioned and recorded by Chanticleer; 12-part voices, but short (under 3 minutes) and with many repeating rhythmic patterns; not too difficult if ensemble is large enough; extremely happy, bouncy, and percussive

Recommended piece: Alegre for band

Available at Hal Leonard; commissioned by the American Composers Forum specifically for middle school bands; very accessible in terms of difficulty; lives up to its name (“joyous”) and has a part in the middle for optional improvisation

Regina Harris Baoicchi (b. 1956)

- Born and grew up in Chicago, Illinois

- Writes for orchestra, voice, many unique chamber combinations; has one opera, Gbeldahoven: No One’s Child

- Style is often contemplative and interior, even in pieces using driving rhythm; Baiocchi is also a poet — perhaps that is why her music seems to look inward; warm feel, but not afraid of spare textures

- Biography and (incomplete) works list at reginaharrisbaiocchi.com

- For access to scores, contact Regina@ReginaHarrisBaiocchi.com

Recommended piece: Muse for orchestra

For score, contact composer through website (recording also available on website); nervous excitement progresses to an expansive sense of triumph and rest; moderate difficulty, 6 minutes long

Recommended piece: Azuretta for solo piano

For score, contact composer through website; soulful, moves through many moods, moderate difficulty; 3 minutes long

Rosephanye Powell (b. 1962)

- Born and grew up in Lanett, Alabama

- Writes for primarily choral ensembles; major work is oratorio Cry of Jeremiah

- Style has strong influence of gospel music, African American spirituals, and other African American musical styles; generally tonal, often upbeat; writes for all choral voicings

- Biography and works list at rosephanyepowell.com (plus detailed work descriptions and publisher information)

Recommended piece: Still I Rise for SSAA or SATB chorus with piano

Available at Gentry Publications; joyful gospel feel; text is by Powell, inspired by Maya Angelou; extremely popular with students

Recommended piece: Sorida for SATB chorus with percussion

Available at Hal Leonard; original work inspired by a Shona word which means “greeting;” most text in English; moderately fast, very upbeat; useful for processions, ceremonies, preludes, etc.

Valerie Coleman (b. late 20th century)

- Born and grew up in Louisville, Kentucky

- Writes for solo winds, chamber music, wind ensemble and band, orchestra

- Concert flutist; founder of Imani Winds; compositional voice is tonal, highly melodic, with interlocking layers that create rich harmonies

- Biography and works list at vcolemanmusic.com (plus info for purchasing scores)

- Some works published by Theodore Presser

Recommended piece: Umoja for many ensemble possibilities

vcolemanmusic.com for different ensemble scores

Umoja is the Swahili word for “unity” and the work is joyful and energetic but also accessible and not difficult; suitable for many ensemble levels and short at under 3 minutes long; as one of Coleman’s most popular works, this piece is available for orchestra, concert band, wind quintet, flute quartet, and flute choir.

Recommended piece: Roma for concert band

Available at Theodore Presser; rhythmic, occasionally raucous, will make everyone want to dance; moderately difficult; 11 minutes long

Recommended piece: Seven O’Clock Shout (written to honor frontline workers) for orchestra

See Coleman’s website for purchasing/rental; first half is stirring, sonorous, and uplifting; second half is upbeat and joyful; 5:30 minutes long; not overly difficult, should be accessible to a good student orchestra

Parting thoughts

Thank you for moving together with me through this list of possibilities. I hope that perhaps you saw a new title that made you perk up, or a familiar title that you had never gotten a chance to listen to, and that you made your way over to YouTube to find it. If this list fired your imagination for programming in the coming year, I encourage you to use all the listed resources to learn about these composers, their backgrounds, their inspirations, and their motivations. Some of the older composers on this list have correspondence and archival materials in libraries around the U.S.; some of the younger composers share their own program notes and analyses on their own websites or have interviews on YouTube and other platforms. My goal is that this article, together with the listed resources for further programming explorations, can assist you in making this the year that you live your values, harness your enthusiasm, and program Black composers!

Resources for further research on Black composers

- African Diaspora Music Project

- AfriClassical & its accompanying blog

- University of Colorado Boulder’s “Hidden Voices: Piano Music by Black Women” project

- Institute for Composer Diversity

- The African American Art Song Alliance

- “Beyond Elijah Rock: The Non-Idiomatic Choral Music of Black Composers” — spreadsheet compiled by Marques L. A. Garrett

- Music by Black Composers

- The National Association of Negro Musicians, Inc.

- “Orchestral Music by Women of African Descent” from Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy

[1] As an off-topic, but related, aside, I would like to suggest the gender corollary, that it is primarily the responsibility of male musicians to program and perform enough works by women and genderqueer composers so that your programs never have a majority of male composers. This is most important in professional ensembles and graduate programs. Because of the steep drop-off in women conductors in the professional orchestras and larger university music programs of the United States, there can never be gender parity on concert programs if only non-male musicians are programming non-male composers.

Many thanks to scholar and singer Max Jefferson for providing valuable feedback on this article.

Thank you Dr. Martin for this wonderful article.