I. The angel in the house

In 1854, the English poet Coventry Patmore published The Angel in the House, a narrative poem extolling the virtues of the ideal Victorian woman. Intended as an homage to his wife Emily, the poem is incessantly long (182 pages in an 1856 edition) and speaks lucidly to a certain type of male fantasy:

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman's pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself.

Though not initially well-received by critics, Patmore’s poem resurged in the late nineteenth century and maintained popularity well into the twentieth. Inspired by the poem’s title, the phrase “angel in the house” came to denote the consummate Victorian (house)wife who exemplified modesty, grace, and utmost fidelity to her husband. This archetype extended beyond literature into middle-class English society, where women — following Queen Victoria’s example — were encouraged to keep to the home, aspire to motherhood, and uphold domestic virtue.

Unsurprisingly, The Angel in the House received criticism from early feminists. In 1891, Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote “The Extinct Angel,” a satirical short story about “a species of angels” owned by human creatures who “kept constant watch over the virtues of the angel, wrote whole books of advice for angels on how they should behave, and openly held that angels would lose their virtues altogether should they once cease to obey the will and defer to the judgment of human kind.” Gilman resolves the hapless angels’ fates by killing them off, reflecting her own hope for women’s independence from the Victorian domestic ideal. Forty years later, Virginia Woolf presented a similarly macabre response to Patmore’s angel through her essay “Professions for Women” (1931). Arguing that her obstacle to professional emancipation was a certain woman “who bothered [Woolf] and wasted [her] time and so tormented [her],” Woolf reaches this conclusion: “Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of the woman writer.” For Gilman and Woolf, the “angel in the house” was a menace — a blight on the social, political, and personal freedoms of women — and she had to die.

As a classical harpist, I bring up the “angel in the house” because she, as an object of male fantasy, is closely tied to the aesthetic and cultural legacy of my instrument.1 My interest in the discourse on gender and the pedal harp, however, is less concerned with advocating for representational parity or the “Women in Music”/“Women are badass!!!” female empowerment arguments (which are, nonetheless, equally important conversations). Rather, I am fascinated by the simultaneous obsession with and abjection — in both music and culture more broadly — of a specific kind of female harpist: the one who bore and still bears descriptors such as “beautiful,” “elegant,” and “angelic.” Thus, this species of “female harpist” is twinned with the “angel in the house” — expected to soothe and entertain, not through domestic work but through music; to charm the public with her beauty and grace; and to satisfy a specific type of bourgeois, heteronormative masculinity that expects women to be sexually attractive but not sexually available. Admittedly, this relationship between femininity and the pedal harp is complex and implicates much broader cultural, social, political, and economic developments in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Europe, England, and the United States. I encourage others to explore this history and to intently examine the intersections that have influenced the lives of women to this day.

For the purposes of this article, I can only offer a miniscule slice of history that contextualizes how the Western pedal harp became associated with women. Harps are old, dating as far back as 3,000 B.C.E, and they comprise a family of instruments, many of which can still be found in African and Asian musical cultures. Ancient harps were played vertically (strung across a bow-like frame) or horizontally (strung over a sound box). The triangular frame harp, which included a column that joined the neck (top) and sound box, is the harp most people in Western cultures imagine when they hear the word “harp.” Evidence of frame harps can be traced as early as the eighth century C.E., and they proliferated in medieval Western Europe via harpers, troubadours, and minstrels. Throughout the European medieval and Renaissance periods, the frame harp experienced waves of innovation as luthiers improved its construction and expanded its musical capabilities through the addition of multiple rows of strings (e.g., double- and triple-strung harps) or chromatic mechanisms (e.g., levers, hooks, and pedals). By the eighteenth century, frame harps in Western Europe had transformed into large instruments that were as mechanically complex as they were lavishly decorated. As the harp evolved from being relatively accessible to increasingly elaborate and expensive, the demographics of its players became more restricted to those who could afford the money, time, and space demanded by these new harps.

Right: A modern Lyon and Healy Louis XV Special harp (double-action pedal), retail price listed at $220,000 (Vanderbilt Music Company). This harp is one of the most expensive in Lyon and Healy’s catalog; the more typical price of a new concert grand harp ranges from $18,000 to $60,000.

Meanwhile, the status of women was changing around Europe, particularly with the advent of discriminatory inheritance laws and the steady push of women from public spheres into private ones. Industrialization in the nineteenth-century led to the rise of the middle class and the development of “middle-class sensibilities” that emphasized such values as family cohesion, cultural refinement, and personal edification through education and leisure. Men were expected to be financial providers, acting as liaisons between public and home, while women took on the role of “symbolic keeper of morality and decency within the home, being regarded as innately superior to men when it came to virtue;”2 in other words, Patmore’s “angel in the house” is exactly what society expected the nineteenth-century woman to be.

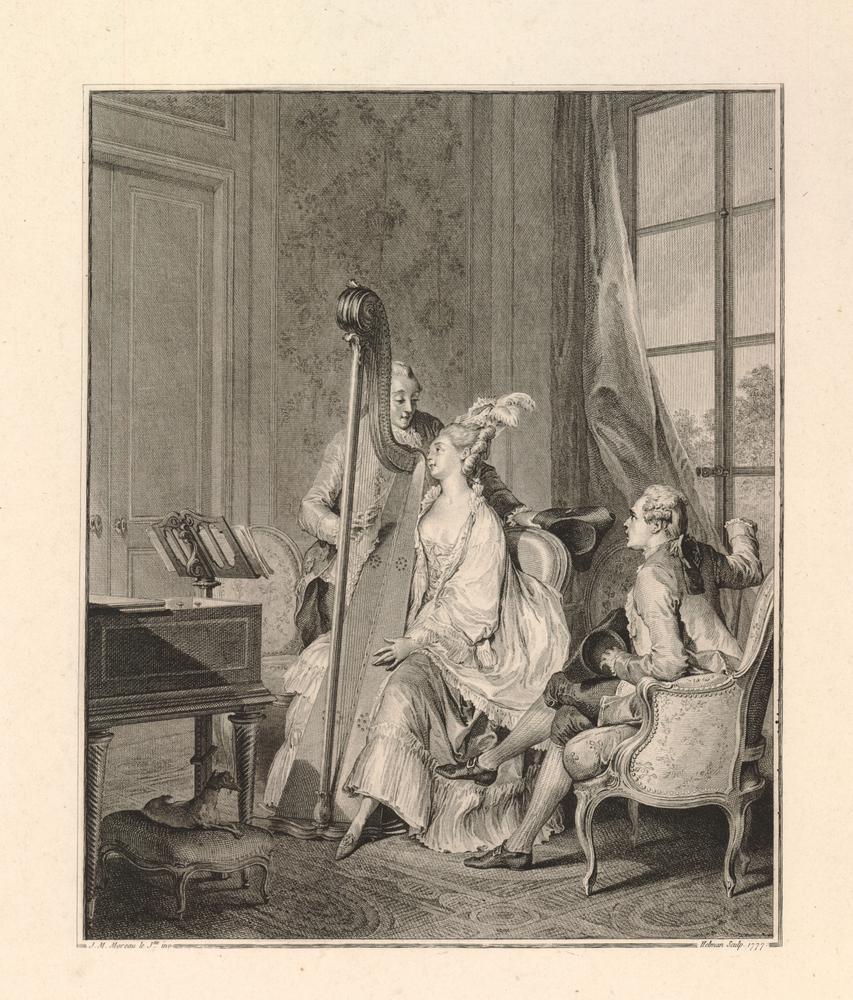

Here is where the middle-class obsession with extolling and protecting female virtue intersects with the harp. At this point, the pedal harp’s relatively large size and lack of portability literally confined the instrument to the home, the central space for defining and living out female respectability. Moreover, receiving some form of musical instruction was ubiquitous for young middle-class women, since musical skill was a “sign of refined femininity, greatly enhancing a young woman’s marriage prospects.”3 For middle-class families, not only did the harp function as a status symbol and a tool for social mobility, but it also became the ideal accessory for highlighting a young woman’s beauty, refinement, and intelligence. More importantly, the harp accommodated the middle-class preoccupation with female virtue and sexual passivity. In eighteenth-century France, “the harp became such a powerful feminine symbol because it struck a perfect balance between conformity to and transgression of contemporary ideas of feminine decency.”4 Playing harp required minimal physical mobility and kept the body partially concealed, yet left just enough to the public eye to titillate the (male) imagination. While the woman at the harp was supposed to represent feminine propriety, her legs are spread (realistically, to keep the instrument in place), her bare arms are gracefully exposed, and her ankles peek daintily from her skirt every time her feet move to change a pedal. By the end of the nineteenth century, this image of the coquettish (yet virginal) woman — a domestic goddess perfecting her wit and musicianship to charm some future husband — had come to dominate the Western cultural narrative about the instrument.

By the start of the twentieth century, classical harpists and composers were eager to kill off the “female harpist” archetype so that they could establish a more “serious” image for the harp, and thus advocate for more robust repertoire and a more respectable reputation as a concert instrument. This new narrative, however, failed to leave behind the weird gender politics in which men somehow still seemed to pull the strings. Carlos Salzedo, an early twentieth-century harpist-composer still widely revered for his avant-garde approach to the harp, was described by harpist Lucile Lawrence (also his former wife and student) as a “world-class harpist who made no bones about being a male chauvinist … [he] was always looking for a male successor … he said a woman would never be able to do it.”5 In a 1957 feature in the New York Times, Victor Salvi, harpist and founder of Salvi Harps, asserted, “The harp is not a feminine instrument—in Europe men are the best players” (Ironically, the article was titled “Instrument Gets a Helpful Angel.”). Luciano Berio, one of the most influential Italian composers of the twentieth-century, wrote his Sequenza II as a reaction against French impressionism’s “rather limited vision of the harp, as if [the harp’s] most characteristic feature were that it could only be played by half-naked girls with long, blond hair, who confine themselves to drawing seductive glissandi from it.”6 Finally, as recently as 2005, Emmanuel Ceysson (now Principal Harpist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic) commented that “there’s this kitsch image of the beautiful young lady like a fairy at her harp. You’re always faced with this. But there’s a reason why the true virtuosi of the past were men, and it’s because the harp is actually a tough instrument.”7 Unlike Woolf’s call to exterminate the “angel” for the sake of female self-determination, the backlash in classical music to the “female harpist” comes across as thinly veiled sexism: Ladies, sit back and watch the men do the work.

A lot of the writing about my music is done through a lens of straight-up sexism and, in other cases, just a coding of feminising of things.

Joanna Newsom, The Guardian

“Where do we go from here?” is the question I often receive from harpists about our instrument’s historically fraught relationship with gender. It’s the question I’ve asked myself many times as I’ve noticed these days how often harpists, both male and female, describe themselves, or are described, as “breaking stereotypes.” That stereotype comprises, of course, the angel in the house and her twin, the female harpist. Taking cues from the likes of Salzedo and Salvi, we’re supposed to supplant her with patriarchal models of progress, innovation, and modernity — to asphyxiate her with newly empowered hands and obliterate her from the public imagination. While part of me agrees with Woolf and Gilman that the angel needs to die, the other part of me wonders why rejecting her has been as much an exercise in misogyny as one in female empowerment.

Something’s not quite right.

II. The ghost in the house

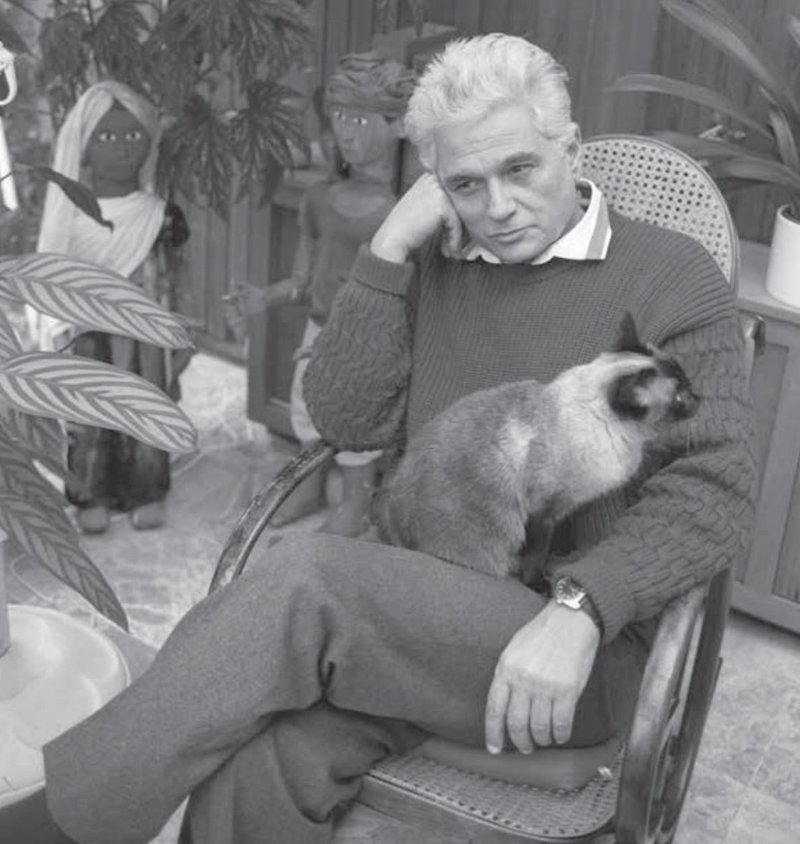

This Thing is the other insofar as it was already there — before me — ahead of me, beating me to it, I who am before it, I who am because of owing to it.

Jacques Derrida

What if the metaphorical death of the angel in the house isn’t the only solution? What if there is a way for her to exist, suspended eerily in a space outside of life and death?

The ghost circumvents the irrevocability of death. It is not undead, in the sense of being neither dead nor alive. Rather, I might argue that ghosts are both: the animate dead and the inanimate living. French philosopher Jacques Derrida was fascinated by ghosts as an ontological metaphor, citing their ability to be “both visible and invisible, both phenomenal and nonphenomenal: a trace that marks the present with its absence in advance.”8 Derrida is saying that the ghost is a remarkable ontological other because it transcends our phenomenological limits: it is able to be (t)here (here and there) and “always-already.” One cannot mark the start or finish of a ghost, since it is always disjunctive ending that keeps returning. Anything that haunts does not comply with a teleological linearity that requires us to accept the past as what has happened and is done. Thus, haunting is recursive and subversive; it asks that we consider how we have inherited the past and how the future and present are animated by the dead.

Derrida called this spectral state of being “hauntology,” which he discusses in his 1993 book Spectres of Marx and “Spectrographies,” an interview filmed later that year. Scholars and theorists have since applied hauntology to a myriad of subjects from music to race, but the context of the term lies in Derrida’s criticism of the post-Marxist, capitalist liberal democracy championed by American political scientist Francis Fukuyama in his 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, along with the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly thereafter, seemed to indicate the death of Marxism, yet Derrida insisted that the spirit of Marx’s critique was very much still present and would persist through haunting. While I won’t get into Derrida’s views on Marx, what I do find important about this context is its broader observation of progress and time: the end of something does not indicate a dissolution. The end returns in the form of a ghost.

In the contemporary Global North, the angel in the house is dead — and along with her, the gendered milieux that galvanized the “female harpist” stereotype. Women, for the most part, now have more political, social, and reproductive rights than they did in the past few centuries. Legally, women are no longer viewed as the property of their husbands, nor are motherhood and wifehood perceived as their de facto roles. Despite this “progress,” women continue to face socioeconomic inequalities and gender-based violence; in the arts, biases against women run rampant, manifesting as imbalances of representation or just flat-out sexism. Thus, the angel, though dead, now wanders through our world as a revenant; she returns to haunt me and every (female) harpist who still feels the weight of her presence. We are caught between inheriting who she is — beautiful, delicate, angelic, refined, pleasurable, consumable — and proving we can negate everything about her, whether through identity (“I’m not a typical cis-het white female harpist!”) or through musical merit (“I play serious/edgy/cool music that shows the harp is capable of more than frou-frou salon music!”) or both. Whatever we do and say, we find ourselves stuck between her and not-her, her spectral body hovering and obstructing our vision with its overwhelming presence.

After the ferociously talented harpist Bridget Kibbey unpacked her 47-stringed instrument at our NPR Music offices, she proceeded to crush the stereotype of the genteel harp, plucked by angels. She proved that the instrument can be as tempestuous as a tango, as complex as a Bach fugue and sing as serenely as a church choir.

Tom Huizenga, NPR Music

Even if we have killed the angel in the house, we cannot kill her ghost. Ghosts cannot die. Hauntology wants us to accept that premise and to understand that we ought not see the past as something to bury. The past returns and animates the future; it hides in our shadows, always with us, always (t)here. Therefore, we must re-think our relationship to the ghosts of the past and to see them not as presences to “be assimilated or negated (exorcized), but as lived with, in an open, welcoming relationality.”9 But what does “living with ghosts” even mean? I speak particularly to those who are female harpists, female musicians, or simply women/woman-identifying: “Living with” is a call to not feel the need to prove ourselves to cultural and aesthetic structures that have been overwhelmingly shaped by men — to not feel we must always play catch-up in a world that wasn’t built for us. It leads us away from the pressure to be “interesting enough” or “brilliant enough” in a patriarchal society, and from castigating the angel for her weaknesses and lack of agency. “Living with” is an invitation for us in the present to exhume her: to understand her on our terms by looking back and wondering if negating her was and is the only way to freedom. It is learning to sympathize with her, to commune with her ghost, and to allow her to accompany us in our pursuit of a more equitable world.

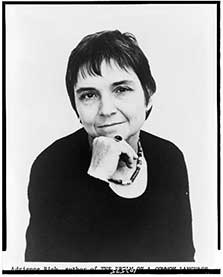

Poet and feminist Adrienne Rich calls this process “re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction.” For Rich, re-visioning is a vital tool for reclaiming and redefining female agency. She writes:

“This drive to self-knowledge, for woman, is more than a search for identity: it is part of her refusal of the self-destructiveness of male-dominated society. A radical critique of literature … would take the work first of all as a clue to how we live, how we have been living, how we have been led to imagine ourselves, how our language has trapped as well as liberated us; and how we can begin to see—and therefore live—afresh.”10

Rich wants us to ask these questions: Whose world made us? Who are we trying to please? Whose standards are we following? Who created those standards? (Of course, the quasi-facetious answer is “men.”) Re-visioning allows women to wrest control of their own narratives, to decide what matters to us and how we want to speak. Rich stresses, “women can no longer be primarily mothers and muses for men: we have our own work cut out for us.” We must contend with our predecessors, explore our histories, and rebuild the myths surrounding us. In the arts, this task is especially daunting, for women have been and are still inundated with the fiction of male genius; thus, we are faced with the pressure to be extraordinary, at the expense of denying or sabotaging disparate realities of womanhood.

the thing I came for: the wreck and not the story of the wreck the thing itself and not the myth the drowned face always staring toward the sun the evidence of damage worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty the ribs of the disaster curving their assertion among the tentative haunters. -Adrienne Rich, “Diving into the Wreck”

We, as female artists, do a disservice to each other in thinking that the only women worth admiring are the ones who broke boundaries and rivaled the accomplishments or “brilliance” of their male counterparts. Womanhood, for many throughout history and even in the present, has not been about being exceptional, at least not in ways recognizable to societies constructed by and for men. We are mothers, grandmothers, daughters, sisters, lovers, and friends: women who care, nurture, struggle, desire, and survive, who are marked by the unremarkable anxieties and unglamorous routines unique to female life. To paternalistic eyes, the woman is a lacuna — a void that must be filled to feel complete — but we must learn to embrace that persistent absence, that fragmented autonomy, as a place where we can “breathe differently”11 and discover our richly embodied selves. In exploring our subjectivities, we re-vision a different kind of world: one in which we are haunted, not by the specter of “male judgment”12 but by the complexities of the female lives that have come before us. This radical acceptance allows us to avoid the paradoxically misogynistic feminism in excoriating the angel, leaving us instead to ponder “I who am before it, I who am because of owing to it [avant moi, devant moi, me devançant, moi qui suis devant lui].”13

Therefore, we ought not wave aside the angel in the house as a limiting stereotype, constantly fighting to prove we have not inherited her inadequacy or melting her down so we can re-fashion her into something newer and shinier. While I recognize that women didn’t necessarily ask to be her — after all, her very existence is a result of the male fantasy — the reality is that we are persistently marked and aggrieved by this objectification. How can we find relief? Rich emphasizes that we must first learn to accept the painful ache of female subjectivity:

“Both the victimization and the anger experienced by women are real, and have real sources, everywhere in the environment, built into society. […] We can neither deny them, nor can we rest there. They are our birth-pains, and we are bearing ourselves. We would be failing each other as writers and as women, if we neglected or denied what is negative, regressive, or Sisyphean in our inwardness.”

In my life as a female harpist, I have wrestled with the angel, and I do not think I will stop anytime soon. Nevertheless, I have learned to resist the urge to deny her and to avert my gaze upon her corpse. Instead, I have re-visioned her as a ghost, seeing her, not as a source of weakness or shame, but as a guide in exploring female consciousness and identity. She is always and already (t)here, reminding us of where we come from and where we must go, for her sake and ours.

Rather than deploring the dead, let us hold on to their ghosts; let us embrace the feeling of being haunted. Ghosts are uncomfortable. Their incorporeality slips through our tangible realities; they watch us, but we cannot return their gaze. They defy our desire to “start anew” by keeping us accountable to the past. They remind us that the dead cannot be forgotten, and that the past animates the future just as life is created by the vestiges of death. So, we become insects unwilling to part with our exuviae: the spectral evidence of former lives, discarded and forgotten. Therefore, even though the angel in the house has been proclaimed dead, we owe it to her to unearth her secrets and to sense the traces of her that persist even after she is long gone. As her ghost returns, again and again, we begin to see her in a new light, and slowly, we learn to live with her.

We are, I am, you are by cowardice or courage the one who find our way back to this scene carrying a knife, a camera a book of myths in which our names do not appear. -Adrienne Rich, “Diving into the Wreck”

Notes:

[1] However, it is important to note that the belief that the harp is or was a “woman’s instrument” is a misconception, since male harpists proliferated and have contributed to most of the current Western classical pedal harp canon.

[2] Susan M. Cruea, “Changing Ideals of Womanhood During the Nineteenth-Century Woman Movement,” American Transcendental Quarterly 19, no. 3 (2005): 188.

[3] Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, “The Music Lesson: A Window of Opportunity,” in Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion, Furniture in Eighteenth-Century France (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 45.

[4] Robert Adelson and Jacqueline Letzter, “’For a woman when she is young and beautiful’: The Harp in Eighteenth-Century France,” in History/Herstory: Andere Misekgeschiechte(n), edited by Annette Kreutziger-Herr and Katrin Losleben (Cologne and Weimar: Böhlau Verlage, 2008), 320.

[5] Sam H. Shirakawa, “A Conversation with Lucile Lawrence,” American Harp Journal 11, no. 3 (Summer 1988): 7-8, quoted in Olga Gross, “Gender and the Harp (Part II), American Harp Journal 13, no. 4 (Winter 1992): 31.

[6] Luciano Berio, “Sequenza II (author’s note),” http://www.lucianoberio.org/sequenza-ii-authors-note?131775360=1.

[7] Michael White, “Bring the Harp Down to Earth, Trying to Make It Rock,” The New York Times, published April 3, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/03/arts/music/bringing-the-harp-down-to-earth-trying-to-make-it-rock.html.

[8] Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, “Spectrographies,” in The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 39.

[9] María del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, “The Spectral Turn / Introduction,” in The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 33.

[10] Adrienne Rich, “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision,” College English 34, no. 1 (October 1972): 18.

[11] Adrienne Rich, “Diving into the Wreck,” Poets.org, 1973, https://poets.org/poem/diving-wreck. Accessed March 14, 2022.

[12] Rich (1972) also notes, “No male writer has written primarily or even largely for women, or with the sense of women’s criticism as a consideration when he chooses his materials, his theme, his language. But to a lesser or greater extent, every woman writer has written for men even when, like Virginia Woolf [in A Room of One’s Own], she was supposed to be addressing women.”

[13] Derrida and Stiegler, 42.