“Well, what do you think? Avanti?”

“Avanti,” cries everyone, and, after a few quick re-tunings of our instruments, and re-initialisings of our hearts, we enter the slow theme-and-variations movement.

How good it is to play this quintet, to play it, not to work at it — to play for our own joy, with no need to convey anything to anyone outside our ring of recreation, with no expectation of a future stage, of the too-immediate sop of applause. The quintet exists without us yet cannot exist without us. It sings to us, we sing into it, and somehow, through these little black and white insects clustering along five thin lines, the man who deafly transfigured what he so many years earlier had hearingly composed speaks into us across land and water and ten generations, and fills us here with sadness, here with amazed delight.

Vikram Seth, An Equal Music

The Immorality of Immortality

I sit down to write my fantasy novel. But today, it’s hard to get started. Yes, it’s the distractions of day jobs and daily life, but it’s so much more as well. I want this novel to outlast me, its ideas and words to echo across generations, for my very soul to shine through its pages, values, and concepts. I want my grandchildren (and I don’t even have children yet) to better understand who I was. I want the novel to be a little evidence that I was here, on this planet. I know that in order to write effectively, I have to enter a state of what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi[1] calls “creative flow,” defined as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake.” In flow states, “the ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.”[2] On the best days, it takes mere minutes to enter that space.

Nowadays, when I feel a growing mismatch between my own values and that of an increasingly calloused America, when peace of mind and societal agency seem to be rarer commodities, it’s getting harder. I’ve watched the richest man in the world attempting to leave behind a storied and lasting legacy by traveling to outer space and battling aging — a narcissistic man carving himself into his own Mount Rushmore with only cash as his chisel. So, as an artist who desires to have his work reverberate through time, what makes me different? Other than the fact that I lack a cash chisel? Is the only difference the nature of my chisel? After all, is that not what we artists intend to do as well, etch our thoughts and lines and colors and songs and voices and images into the permanent records of history? But, conversely, if art doesn’t last, what’s even the point? For Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006), celebrated Poet Laureate, “the supreme morality of art is to endure.” Sir Terry Pratchett (1948-2015), best-selling novelist, wrote that “no one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away.”[3] Maya Angelou (1928-2014), poet and civil rights activist, demanded, “If you’re going to live, leave a legacy. Make a mark on the world that can’t be erased.” Well, by God, yes, I want ripples. I want a legacy. I don’t want to be forgotten. And if my art doesn’t endure, what purpose did it serve?

But then, what makes my journey to remain any different than that of a billionaire attempting to download social media directly into our eyes while the world burns? Whether immortal or immediate, the pursuit of art seems immoral. And with thoughts like these, how can I possibly expect to experience ‘flow’? To conquer the blank page? To put my soul into my work?

Again, that word.

Soul.

My soul.

My atman.

The Search for Soul-Peace

The word atman is as familiar to me as the walls of the room where one lived their childhood. I was born in India but moved to North America at the age of four. I was raised in a brown bubble in a white world, and am equally comfortable moving through each. I always felt the two didn’t intermix, though, that it was somehow my duty to be whole in each without the other. Those who knew me in one context were frequently unaware of my other side. I have shocked countless American friends who, after having known me for years, are surprised to discover I can speak, read, and write in another tongue. I suppose in some ways, as a child who moved from one world to another before my inner self had a chance to even halfway develop, my soul has always been split into two separate but equal segments. I’ve never thought of it this way before; perhaps the solution to my dilemma is in that desegregation. Perhaps the answer to these questions I ask while seated in the Western world resides in the Eastern bubble of my upbringing.

Atman[4]is a Sanskrit word that first appeared in the Rig Veda, a foundational book of Hinduisim, written at least a thousand years BCE, a word that has been translated (perhaps paradoxically) as both “soul” and “self.” As a concept, atman is central to discussions of morality in Eastern religion and key to understanding the unbridgeable divide between Hinduism and Buddhism. For any modern artist committed to morality within their work and lives — because, as W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) asserted, “Art, unless it leads to right action, is no more than the opium of an intellegentsia” — I believe atman is fundamental to both the process and the rewards of “creative flow.”

My own first understanding of atman is probably best translated as “spirit,” even in the phantasmagoric sense. Similar to the Western concept of a ghost being unwilling to leave the mortal world because of “unfinished business,” a ghost in Hinduism or Buddhism remains behind because it has not achieved soul-peace (or atman-shanti). A phantom atman lingers miserably, believing it has not done enough, unwilling to accept the central reality of its changed condition, watching all remnants of its mark upon this earth fade before its eyes. This metaphor haunted me throughout my youth; I related to it on some ineluctable psychological level. I have lived years, due to abandonment and trust issues, feeling like a barely living ghost, incapable of true and lasting touch, simply wandering the world invisible, unfelt, and unremembered. It is my recurring nightmare, even today.

A Frightening Anathema

While major Indian philosophy struggles to concretely define atman, the six orthodox schools of Hinduism all agree that it resides in each living soul (known as jeeva). The word itself is denotatively linked to prana, the Sanskrit word for “breath.” It is the element that enters into us at some point after conception and that leaves at the point of death. It is the “innermost essence” that is then reincarnated into future forms. Divergent schools of Indian philosophy argue about the interrelationship between and nature of Jeevatman (the innermost individual self) and Paramatman (the Supreme, or Divine, Self). Where is God’s — or the Universe’s — self? Within us? Within the world around us? Are they one and the same? Or are they different? Yet, regardless of these differences between Dvaita, Advaita, and Vishishta philosophies, one tenet remains consistent: the atman is unchanging throughout eternity, and it is all we leave behind once the jeeva has left our bodies. It is a psychologically comforting thought, to know that we contain within us a nonmaterial essence that is both eternal and unchanging.

Western theology, for the most part, agrees. Ideas of heaven and hell speak frequently of “souls,” though more in the vein of Jeevatman than Paramatman, clearly separating God’s soul from our own. What is rewarded in heaven or punished in hell is our own souls, so that justice may be rendered unto each sinner according to their own individual behavior. This Mesopotamian cleaving of “soul” and “self” is in some ways the most critical distinction between Hinduism and the other major world religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Catholicism, humans may have the Holy Spirit inside of them, but it would be blasphemous to claim that each individual’s soul is no different from the Holy Spirit.[5] (Small wonder, then, that artists in the West seek to be simultaneously “soulful” and “selfless” with no feeling of cognitive dissonance.) Still, in each of these four major religions, the benefits of a soul-based and/or self-based approach seem obvious: it gives humanity something to believe in and a comfort in knowing, at the end of our lives, that we were not impermanent, that our words and actions reverberated at cosmic levels. Regardless of whether it was “soul” or “self,” we could agree we all left something behind. We all mattered. We all had legacy.

Until Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, came along and took away even that small solace of our only foothold into eternity.

Around 500 BCE, the Buddha posited a controversial and theretofore unheard-of philosophy surrounding the atman, causing the primary schism between Hinduism and Buddhism that made them irreconcilable in core philosophy, despite their shared origins of history, geography, and language.

Essentially, depending on which historian you believe, the Buddha claimed either that there was no atman (no soul, no innermost essence of the individual self) or at least that there was no point in seeking it.

No soul. No self. Nothing left behind. Only an aspiration to oblivion.

His ideas became known as anatman or anatma, an idea of soullessness so shocking that, in the English language, it currently resides within the pejorative term “anathema,” pertaining to ideas that are unholy, repugnant, or repellent.

My nightmare of being a ghost was the Buddha’s ideal.

Why? Why would the Buddha repudiate both self and soul? What possible benefit could there be in believing that there was nothing permanent inside of us, nothing that would survive us after we had gone?

The Benefits of Anatman

The first benefit of the philosophy of anatman is perhaps the clearest. The Buddha argued that morality in hope of future reward (a place in heaven or reincarnation as a higher being) or for fear of punishment (reincarnation as a lower being or damnation to Hell) is in fact not true morality at all.[6] These are acts done by a child in favor of a treat or to avoid a scolding. This idea that morality for reward/punishment is juvenile and pre-conventional echoes throughout the centuries, even as recently as 1958 in Lawrence Kohlberg’s theories of the Stages of Moral Development.[7] True moral acts are not done unconsciously or even subconsciously but as a result of conscious decision-making. The focus, argued the Buddha, must be on conscious choice. Only then will morality be a result of our human experience and faculties rather than an ineffable echo of the spiritual or supernatural. To him, the very idea of an unchanging permanent soul incentivized human beings to behave without true consciousness, and therefore made morality inactionable, prone to societal, religious, or cultural corruption.

The second benefit to anatman, according to several Buddhist scholars (among them the Dalai Lama)[8], is that it eliminates future-based thinking in order to allow the individual to stay within the present.[9] The implication that there is nothing beyond our sensory experience of the moment encourages us to fully indulge the here and now. Staying present — without “expectation of future stage” or “the too-immediate sop of applause,” as Vikram Seth describes above — allows musicians to truly experience and project the joy of music, between the players, between the artists and audiences, between the pages and the instruments and yes, even between the performer and their prana. In this way, Buddhist doctrine wonders if there is any crime to the act of music-making (or the larger act of morality) being simply conscious, thoughtful, practiced, and immediate.

But the third benefit is perhaps the most psychologically difficult to accept. According to the Buddha, the source of all duhkha (grief) in the world is due, at some level, to someone holding onto the idea of permanence, leading to a gaping wound in their atman-shanti. The doctrine of anitya (impermanence) asserts that all of conditioned existence, without exception, is transient and inconstant.[10] Rupert Gethin, Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Bristol, translates from The Four Noble Truths: “As long as there is attachment to things that are / unstable, unreliable, changing and impermanent / there will be suffering—.”[11] This idea, while seemingly easy to understand, is much harder to accept. When the British attempted to colonize the world, it was justified by some romantic idea of the permanence of Britain. The Crusades were justified by a belief in the permanence of one God over another. The “conquering” of the American West was justified by the Manifest Destiny of American permanence. When a billionaire amasses wealth beyond what they can spend in their lifetime, it is with the desire that their name, legacy, lineage, or wealth itself should be permanent. Yes, those acts are immoral, many of us freely admit, but what about other ideas of permanence? When a husband loses his wife of thirty-five years, it is with the certainty that their love — and their very life together — should have been permanent. When a civil rights activist marches in protest, it is with the conviction that their ideology should become permanent. And when I set pen to page, I want my stories to become permanent.

Where is the sin? In all of them, the Buddha claims. All of these, no matter how noble or relatable the intention, lead to duhkha — both mass-scale and individual — and the Buddha demands that in order to end duhkha, we must not believe in anything permanent.

All things change. And therefore, the atman — when defined as an unchanging essence — cannot exist (or if it does, we cannot know of it). It is in reflection of this central tenet of anitya that, to this day, Tibetan monks in Buddhist monasteries painstakingly craft intricate and beautiful sand or rice mandalas over a course of days or weeks and then, once their masterworks are finally done, destroy them, dissolve them, or feed them to the birds.[12] Not only does this fly in the face of conventional Western artistic philosophy — it even seems immoral.

To the Buddha, the idea of atman obstructs human evolution towards moral development, encourages unself-awareness over consciousness, and provokes all worldly grief. The price of the atman is not worth the benefit of the psychological comfort provided.

So, according to the Buddha, your legacy does not matter. Your moment is, simply, only now.

A Starry Night, Witnessed by One

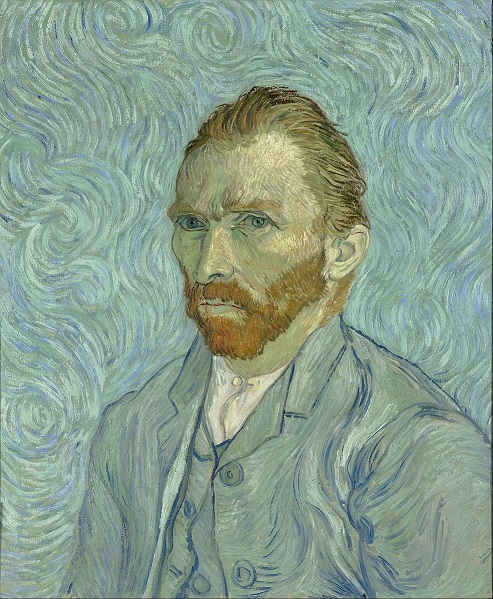

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) was largely unknown in his time. He committed suicide at the age of thirty-seven, succeeded by his brother Theo who swore to take Vincent’s art to prominence. Theo died six months after Vincent, leaving the task unfinished. It was Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who would eventually make the painter prolific.

One of his most iconic and famous paintings is, of course, Starry Night (1889), painted one year before his suicide and one year after he famously mutilated his own ear. Vincent van Gogh painted the dream-like landmark oil-on-canvas piece while being held at the Saint-Paul-de-Masole asylum in Saint-Rémy, France. While the painting depicted the view from his room, he was not allowed to paint there, so it is a rare work van Gogh painted without reference. He applied paint directly from tube to canvas, without brush, speaking to a frenzied and immediate mindset, with no patience for intermediary steps in the process. The result is the image’s iconic thick lines, intense colors, and deep textures. What was van Gogh thinking as he painted? Was he thinking of the potential of his own legacy? Or was he focused on the sensory nature of his own experience, the idyllic scene remembered from his window filtered through the violent tumult within his own mind? Whatever the truth, it is my opinion that his atman, whether soul or self, is clearly embedded within the painting, his mania and genius and daring style all in evidence. He painted with no intention of being “soulful” or “selfless” that night; he simply lived in that moment.

But here is the central irony of this tale. After he had completed Starry Night, Vincent wrote to his brother about the painting, “All in all, the only things I consider a little good in it are the Wheatfield, the Mountain, the Orchard, the Olive trees with the blue hills and the Portrait and the Entrance to the quarry, and the rest says nothing to me.”[13] These facts are therefore unquestionable: Vincent van Gogh largely believed Starry Night to be a failure, did not believe it would endure, and did not even ascribe to it a lasting resonance or legacy. Yet, it is one of his most famous works, studied and beloved, the result of a night of feverish sensory experience now echoing across time. There were many in that town on that night, but only one saw the stars as he did. He was the only witness to what he saw in his mind’s eye, and therefore the only one who could communicate it. Lost in his own mind, submerged in the monumental task of immediate expression, van Gogh found legacy.

Embracing the Paradox

When Buddha speaks of souls and legacies, he is speaking of attitudes and behaviors. Uppadana[14] (or attachment) is the source of all suffering, according to Buddhist doctrine. The more we attach ourselves, the more we lose our selves. This paradox strikes a chord with me because writing is filled with so many of these little ironies. It is a well-known axiom in literature that if you write to satisfy a mass audience, you always lose. Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) famously wrote in his eight rules for writing: “Write to please just one person. If you open a window to make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.”[15] The more you write for one, the more chance you have of writing for all. Similarly, if you write for a legacy, you will never have one.

If we cling to our souls, we lose them. But if we truly forget about them, instead indulging only in our consciousness of the here and now, they mischievously begin to sneak into our work. In this way, anatman can be perceived to be less about truth and more about actionable process.

You’re not a ghost among humans as you have always feared, Buddha seems to whisper to me across the generations. We are all ghosts, and you will attain atman-shanti when you recognize that it is time to let go of the traces of your past self that you seek in the world. And in this moment right now, you are as human as you can ever be, but it too will fade, it too will be gone, it too will leave nothing behind. And that is truth. And that is a joy.

So here I am, at my desk, preparing to write my fantasy novel, trying to capture that elusive “creative flow.” Before I begin, I try to unite the segregated pieces of my soul, release all to which it clingingly attaches itself, and then strive to release that soul itself. I think to myself, I do not care to be remembered. I even aim to be forgotten. My legacy does not matter. What matters now is the way my fingers feel across my mechanical keyboard, the way the light suffuses the room, and the steady and sonorous sound of my breathing. What matters now are these characters, their goals, this world within my mind in only this moment. I choose to believe the words of the Buddha. I have no Jeevatman. There is no Paramatman. All things will change; this moment I have right now I will never have again. It’s an exquisite opportunity, a crystalline and sharp-edged shard of time to use words (or brush or musical tones or fingers or chisel) in such a way, in such a moment that I will never again be able to recreate. Morality exists not in this tome’s survival, and not deep in some unknowable nonmaterial part of myself, but in my conscious and active mind. Though I release my soul, I do not release my self; I explore it instead, with courage, awe, and full transparency. I am a ghost, and as such, I can insensibly choose to watch the residues of my past selves fade into nothing, or I can choose to communicate all that only I can witness from this mindful, immediate, and sensorily dizzying phantom vantage point. I breathe and I feel and I think… and I write.

It works for me.

Mostly.

End note: Thank you to editors Dani Nutting and Elisa Moles of The Collective for their vision, input, and notes through all the drafts. Though I am not a musician, it is an honor to be a part of the Collective when it is overseen by two artists who have an appreciation of the holistic and complementary nature of all of the arts.

[1] https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/mihaly-csikszentmihalyi/

[2] https://www.wired.com/1996/09/czik/

[3] “No one is finally dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away, until the clock wound up winds down, until the wine she made has finished its ferment, until the crop they planted is harvested. The span of someone’s life is only the core of their actual existence.” – Terry Prachett, Reaper Man

[4] https://www.learnreligions.com/what-is-atman-in-hinduism-4691403

[5] https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/dictionary/index.cfm?id=33977

[6] https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/the-ethical-significance-of-the-buddhist-doctrine-of-non-self-anatt

[7] https://www.simplypsychology.org/kohlberg.html

[8] https://www.relicsworld.com/dalai-lama/to-be-in-flow-means-to-be-totally-absorbed-in-whatever-one-author-dalai-lama

[9] https://www.lionsroar.com/the-moment-is-perfect/

[10] https://www.vridhamma.org/node/2489

[11] Rupert Gethin (1998). The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, p. 74.

[12] http://longleaf.net/wp/writings/dissolution-mandala/

[13] https://www.artandobject.com/news/brief-history-van-goghs-starry-night

[14] https://www.learnreligions.com/why-do-buddhists-avoid-attachment-449714

[15] http://newyorkwritersintensive.com/kurt-vonneguts-8-rules-for-writing/

Wow. There’s so much to unpack here. Thank you for sharing. I’ve never really thought of religion in terms of practical artistic application before. This makes me want to read a lot more about the correlation of all the religions to artistic process. And that’s saying something from an atheist. Also, do you think a lot of minority immigrants feel that separate but equal thing about their different cultures?

i loved how this wrapped up. It’s basically a study of what living in the moment really means and where it came from. i hope your writing is less stressful after writing this

Now is the means to all ends.

Really enjoyed your article.

Two new books. Nevermindfullness

Raising your Guilt Threshold

XO