Coming hard on the heels of a year and a half of no theaters and no real prestige film, David Lowery’s The Green Knight was a balm for movie lovers after a rocky reopening full of banal blockbusters. In many ways, the film fulfilled its promise to take viewers somewhere both wonderful and strange, providing stunning visuals, atmospheric tone, a moody and disorienting soundtrack, and incredible performances all around — enough to almost forget one’s anxiety about sitting in a theater with only a mask and vaccine between movie-goers. It was shortly into the film, however, when I felt a twinge motivated by a sense of politics. This was followed by the growing feeling that the movie was trying to do something —in particular, to engage in a form of racial, if not specifically cultural, representation of hybridity. Initially, hybridity was developed as a theory of language and culture that considered how colonized people resisted colonization by mixing social and cultural practices to destabilize the binary between colonizer and colonized populations. Later, it grew to be a way of speaking generally about the range of social, cultural, and racial mixing that happens in a world fundamentally shaped by colonialism.

Ostensibly set more than a millennium before European global domination, The Green Knight would seem to be an unlikely candidate for this concept. However, thanks to a set of artistic choices, casting in particular, the film presents a deeply important case for recognizing that the colonial, and the use or misuse of strategies like hybridization, is rampant in global culture.

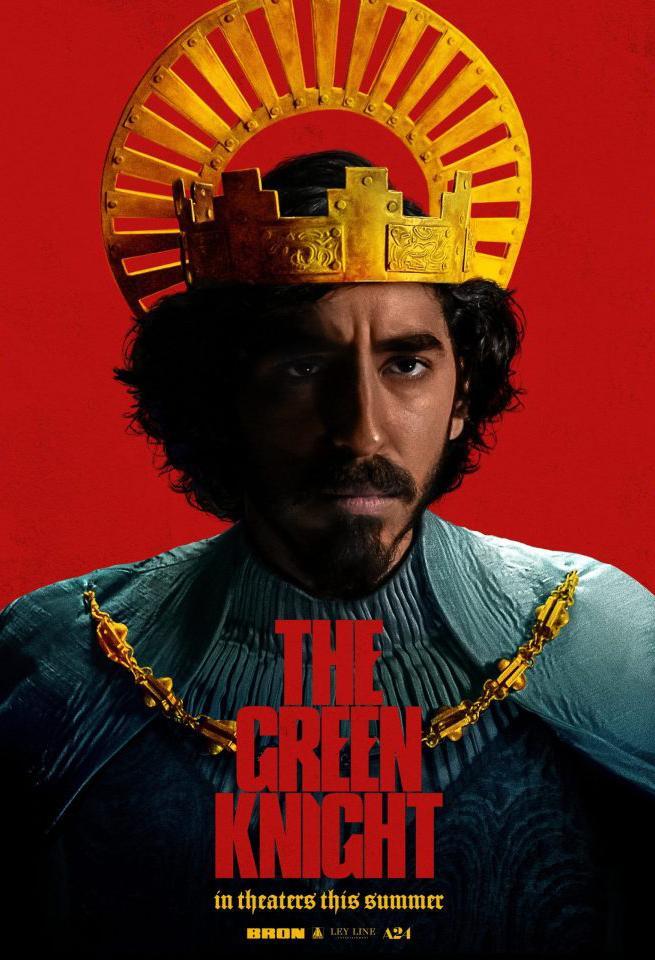

Reviews and social media responses split into two largely predictable camps: professional reviews were effusive in their praise of the artistry and craft, while a contingent of right-wing respondents were outraged at yet another supposed blow against historical accuracy by “colorblind” casting in the form of Dev Patel’s Gawain and Sarita Choudhury as his mother.[1] This critique, nothing but a racist dogwhistle whenever it is raised, is consistently absurd on its face. Leaving aside whether nitpicking “accuracy” really matters in fiction, and how contemporary ideas of race could be “accurate” for distant parts of the past (as historians like David Olusoga have tirelessly demonstrated), Britain was never a homogeneously white country, and it is instead whitewashed films like Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk that should be taken to task. In the case of The Green Knight, however, the casting is neither colorblind nor a case of progressive political reinterpretation. It is, rather, a situation of deeply misunderstood hybridity — in some ways like 2002’s Bend it Like Beckham, which mistakes racial/colonial presence as sufficient, ignores the nuance required of an actual critique of colonial and postcolonial culture, and (perhaps unintentionally) goes on to reinscribe a deeply conservative and pro-colonial politics.

This seems perhaps overly obvious to say, but is nonetheless an important point: Arthur, Gawain, and the Green Knight were not real. They are based not on historical people but on characters in an overlapping series of poems collectively known as the Matter of Britain, which deal largely with Arthur’s court and the quest for the Holy Grail. Though it is a work of fiction, this certainly doesn’t mean that the original poem can’t tell us anything about medieval Britain itself; as a number of commentaries on the film by professional medievalists discuss, the poem demonstrates that medieval people were just as full of complication, contradiction, complexity, and doubt as their modern counterparts. This theme is amply shown in the film, particularly in Patel’s performance, and there is certainly nothing wrong with that. There is, however, a problem posed by the fictional and mythic nature of the material, leaving aside the fact that we have no historical markers to compare story to “reality.” Myth is accretive — that is, even if we have access to original forms of poems and stories, popular understanding carries with it all the reinterpretations, additions, and deletions of the intervening centuries. Further, myth is a deeply political form of storytelling, serving as a convenient pool for ideas about belonging, identity, and personal and group meaning. Texts as early as Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606) or Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590) show how British authors readily reshaped medieval stories and history, particularly the founding myths of England, Scotland, and Wales, into new forms and visions, sacrificing historical accuracy and fidelity of the original in favor of contemporary political usefulness. Interpreting any mythically-derived contemporary art with reference only to the original source material is a fundamental misunderstanding of the way that both myth and history work. While Arthur stories can tell us a great deal about the Middle Ages, we also need to understand how they carry with them meanings and politics of the time in between —meanings which can’t be simply set aside. In the case of The Green Knight, this means that both new artistic representations of the original myth and critical looks at that new art cannot use the medieval context in isolation but do and must take into account all of that myth’s accretions, including, in this case, thorny issues of race and colonialism.

Arguably, the social and political importance of the idea of the Middle Ages in Britain hit a high point during the nineteenth century. Poet, illustrator, and political radical William Blake solidified a Romantic tradition in which pre-modern Britain was to be a model to demonstrate all that was wrong with his contemporary social and political milieu, improbably joined later, if in slightly different form, by conservative novelist and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Religious reformers like John Henry Newman sought to reinvigorate Anglicanism by returning to ancient and medieval Christian practices, often at the expense of much newer English Protestant traditions. Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) created a craze for medieval historical fiction and largely set the tone for most medieval-minded fiction through today. Artists like Gabriel Dante Rossetti and William Morris ensured that the Victorian aesthetic was overwhelmingly inspired by medieval design. Perhaps most visibly, driven by critic John Ruskin, the Victorian period was dominated by a resurgence of Gothic architecture; it is instructive to note that the most famous British Gothic building, the Palace of Westminster (with “Big Ben”), was built between 1840 and 1876 and is not an actual medieval edifice.

But all of this is to say, if David Lowery’s Green Knight owes a great deal of at least unconscious inspiration to nineteenth-century ideas rather than “true” medieval sources, what of it? If living in the shadow of the Victorians was a crime, we would all be guilty. Instead, what does stand out, and the thing that moves the film from an interesting piece of medieval reinterpretation to a potentially questionable bit of neo-Victorian myth, is the incorporation of another major obsession of nineteenth-century Britons: India.

After nearly losing control of their Indian possessions in an 1857 uprising by Indian soldiers, the British needed to find a way to legitimize their continued domination of the subcontinent and to incorporate Indians into the project of British rule. And much like how the Middle Ages were used in Britain, the colonial regime leaned upon ideas of tradition and cultural incorporation. As appeals to pre-modern England were used to create new ideas about British nationhood, the concept of the British as “traditional” rulers was used to normalize colonial rule in India. As an extension of this idea, writers and artists, notably Rudyard Kipling, actively created fictional models of Victorian India’s social world that suggested that Britain and Britons were an indelible part of Indian society. The fact that Kipling’s works, despite his deep and obvious racism, remain the primary cultural entry point to India for the English-speaking world speaks to the power of this project. In the cases of both the Middle Ages and India, the British actively used ideas of tradition, history, myth, and timeless feeling to create a sense of an organic and unassailable foundation at the root of the British state and its empire.

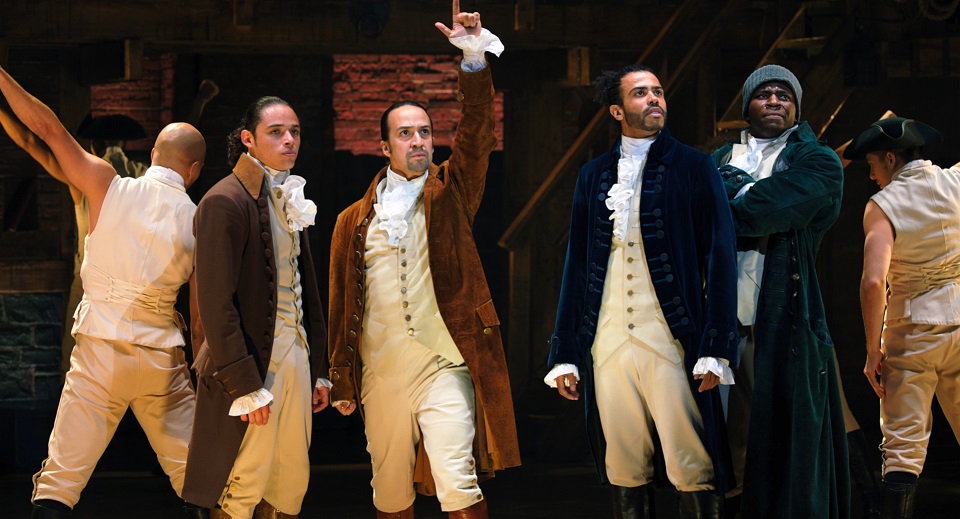

This brings us back to The Green Knight and its casting. Again, the general notion of casting actors of color in historical British films is certainly not an issue in itself and, if anything, would lead to more historically accurate portrayals of the British past. There are, however, specific issues in the particular case of The Green Knight. This does not seem to be an attempt at colorblind casting. While one cannot presume authorial intention, the fact that both Gawain and his mother are portrayed by actors of South Asian descent (both Patel and Choudhury are British) suggests that the characters’ race is not something to be looked past by viewers, as with colorblind casting, but something really present in the narrative and the world of the film. There are other moments that heighten this sense of intentional otherness, including that Choudhury’s unnamed Mother is generally at a remove from the overtly Christian court, and indeed puts the action of the film in motion via the casting of clearly non-Christian spells. Additionally, Gawain’s “gold” cloak from the poem seems to mostly take on much warmer, spice-colored hues, reflecting an at least quasi-racialized color palette.[2] At first glance, this would seem to be a relatively progressive act — removing whiteness from the heart of Britain’s founding myth and its royal family might even be interpreted as an anti-racist cultural stance. Like Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton (2015), however, the collision of real-world history and politics on the one hand, and ostensibly racially conscious casting on the other, instead leads to a deeply reactionary politics of racial assimilation. In Hamilton, the casting of Black actors to portray committed slaveholders raises questions of the psychic cost of assimilation to a white-centric notion of “American” and what happens when hero-worship and national foundational cults are prioritized over sustained historical critique. In The Green Knight, this casting implicitly asks us to understand that, at least from a mythic perspective, India was always part of England and the British story; by extension, this suggests a reading in which the violent conquest and domination of the world was something that colonized peoples had done to themselves. Even if, as the ending of the film suggests, Gawain does not survive his encounter with the eponymous knight, the fact remains that Britain’s mythical founding king/dynasty should now be considered multiracial, and that India was in the blood of England from the start. This moves Britain’s conquest of the subcontinent from a violent series of indefensible aggressions to a more-or-less preordained rowdy family reunion, just as slavery in Hamilton becomes something that Black Americans participated in at the highest levels, rather than a clear act of white supremacy.

In a sense, what I want to propose is The Green Knight as something of an unholy meeting point between three distinct but interrelated cultural projects. First, nineteenth-century British thinkers and artists drew from the Middle Ages to both critique and legitimate their society and political structure, creating a deeply-felt link with a past that they had freely reinterpreted. By postulating a utopian past, these thinkers could attempt to unify the British nation in the present, both by creating a mythic space of previous belonging and peace and also by opening up the possibility of a future grounded in that mythology instead of the grime of the nineteenth century present. Second, many of those techniques were used to promote a sense of organic link between Britain and India in order to secure Britain’s imperial control. The centuries-old relationship between the two was recast not as a profit-driven violent conquest, but as something more of a family relationship, with Britain the benevolent elder to India’s growing child. Resonances in art, culture, and religion were all used to suggest that these two cultures had something ineffable in common that brought them together, serving to turn a relationship based purely upon violence into one of natural love. Third, moving to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, postcolonial writers like Salman Rushdie and Helen Oyeyemi point out how, after the start of European colonial projects, colonized people were incorporated into former colonial metropoles. The empire was not something that happened exclusively “over there,” it created massive change “at home” as well, through immigration, language, food, and everything else. These projects are all incommensurate: Victorian medievalism was intended to showcase the historical legitimacy of a white Britain; Victorian colonialists would never have considered miscegenation, however imaginary, as an acceptable strategy to create imperial unity, and postcolonial literature and theory sees hybridity as a condition of colonialism, not something that pre-dates it. Lowery’s film blithely ignores these tensions and jams all three together, creating a Victorian myth for the post-racial age. Indeed, by moving from a model of racial purity to one of racial assimilation, The Green Knight succeeds beyond the wildest dreams (or nightmares) of Kipling or any other imperial propagandist. As the notion of Britain in India slowly fades from global cultural consciousness, we now have a gorgeous, compelling, and entirely believable foundation story that links England and India better than The Jungle Book could ever hope to.

Assimilationist narratives such as Hamilton (and, I argue, The Green Knight), ask viewers to flatten the past, cut out the history from the myth, and fundamentally ignore the deep problems associated with historical accretion. The point is not that history is better whitewashed, or that history, literature, and art shouldn’t resist racism. It is rather that a Black Jefferson or South Asian Gawain manifestly do not contribute to a politics of antiracism. An uncritical or confused politics of representation, ignorant of historical and artistic nuances, upholds, even if paradoxically, some of the most conservative parts of the myths portrayed. By making the American and British past something post-racial and post-colonial, these narratives erase the past and present trauma of colonial and racial violence. Yes, these films can make us feel good, but at what cost?

[1] “Colorblind” here means disregarding race as a factor in casting, both by ignoring it as a factor in choosing actors and by removing racial logic from the narrative world, including in familial and social contexts.

[2] The question of Lowery’s sense of racial sensitivity is not helped by a deeply troubling scene in his previous film, 2017’s A Ghost Story, in which a group of unseen Native people, portrayed only by off-screen whooping and arrows, slaughter a white settler family to provide some historical trauma for the white protagonist.