That isn’t ethics. Ethics is a real discussion of the competing conceptions of the good. This is just the corporate anti-shoplifting rules.

Oscar Martinez, The Office

What Paul says about Peter tells us more about Paul than about Peter.

Baruch Spinoza, The Ethics

There is a third quote that guides this essay, much more than those two. I must, however, delay its articulation until the moment is right. While we wait for said moment, why don’t we hear a story? This one is fairly short, so no need to get comfortable.

Mikey T and some Colombian Plantations

When (now) renowned anthropologist Michael Taussig went to the Cauca Valley in Colombia to do his ethnographic research in the 1970s, he stumbled upon something us Moderns would consider very odd: the native population was convinced that The Devil had been sighted in their valley. Rather than going along with a more traditional boring and tedious metaphorical or psychological analysis that so often happens when one encounters claims of The Devil in the anthropology of religion, he took the claims absolutely seriously. The result? A groundbreaking work on the way humans understand their objective social situation.[1]

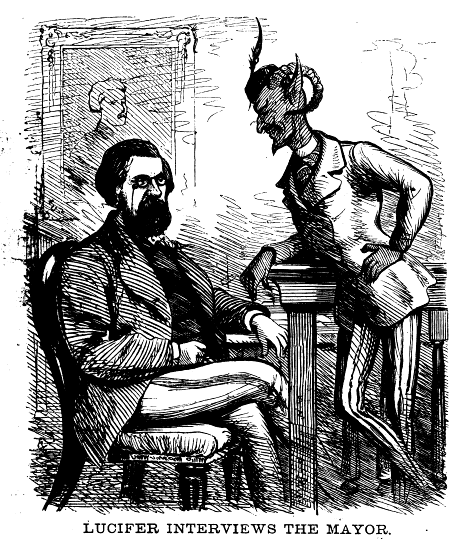

You see, the 1970s was when the capitalist plantation model was being implemented in the Cauca Valley. Prior to its implementation, indigenous arrangements of work, power, etc., were common. It is unsurprising, then, that workers were perplexed to see material wealth amassing among those who were not working. Some humans were robbed of their time and the value they created while those who were already wealthy and did not work somehow gained more material wealth. This accrual of wealth via the exploitation of general laborers was not simply a bizarre and foreign concept to the native population — it was a truly unnatural and Evil one. What Taussig neatly shows is that capitalism itself was the great Evil behind the sightings of The Devil.

The key for me in this story of Mikey T is that rather than assuming the native population was ignorant/wrong/backwards/etc., he assumed they were absolutely right, and in so doing came to the previously stated startling (or not so startling) analysis. My takeaway? Humans know when they’re being fucked. It’s drawing the proper conclusion about the fucking that’s the trouble. A horned demon wasn’t literally making a pact with the plantation owners, but that is oddly closer to the truth than our own disgusting explanations, like: the owners were building wealth / that’s the way the world naturally works / the workers were ultimately better off / “progress” is an inherent good / etc. Might this very human capacity — to relegate abhorrent and unnatural social relations to the realm of the fantastically impossible — be related to the absurdity peddled about celebrities running an underground pedophilic prostitution ring beneath pizza joints around the country? While this is an absolutely stupid conspiracy theory, I do think conspiracy theories, like religious theories, unwittingly reveal truth. Just not in their explicit content. The Truth is so much more absurd than the lies we tell ourselves.

How about that quote now? Yes, it seems we could be ready for it.

I am I and my circumstances.

José Ortega y Gasset

Ortega is a fun read, but I am not an expert on him by any means. I present this quote ripped from its own circumstances for my own selfish reasons: to make it a seemingly arbitrary starting point for the insufferable lecture to follow. To be quite clear, I will not be doing a meaningful and accurate reading of Ortega’s philosophy. That said, the quote does come off to me as typical of a phenomenologist (which Ortega could certainly be considered): the assertion is one of Being, being-in-the-world, authentic being, etc. While I am not at all opposed to some good ol’ fashioned speculative phenomenology, it is always interesting how nearly all phenomenological assertions miss a crucial point, a point rectified by a dialectical reading. What do I mean by this? Simply that any assertion about the world is always articulated from a particular position, and that particular position is shaped by the very world about which one is asserting. Assertions don’t just happen: a particular subject does the asserting. And because of this, we might add a clause to Ortega’s well-known quote: I am I and my circumstances, as I understand I and my circumstances. Or, put more accurately but less pithily: I am I and my circumstances, which makes my understanding of my circumstances a fundamental part of I.

While this may seem like some tautological semantic BS, a moment of reflection reveals something more interesting: our understanding of our circumstances defines our understanding of our selfhood. Thus, how we analyze our experiences — the conclusions we draw from our perceptions of the objective world — radically shapes our understanding of the very “I” doing the perceiving and analysis. Mikey T’s Columbian laborer friends understood themselves as a certain kind of “I” in certain circumstances — “I” at the mercy of supernatural forces. And surely as no mere mortal can defeat The Devil, this “I” is unable to truly act. But if this “I” was understood to be in slightly different circumstances… maybe then The Devil wouldn’t be so lucky.

You see, I have a hunch that a major block for any proper social and material change in the world is the very mechanism by which we understand ourselves. So often either A) we think of ourselves as radically autonomous individuals living in a pre-given “natural” world that we in essence are alienated from (think the Christian soul or neoliberalism — the individual as separate from society, culture, etc., and the economic, social, and cultural processes present as natural, i.e., not humanly produced and reproduced by us), and/or B) we radically fail to accurately analyze our circumstances that, in essence, are a part of our very identity. That is to say, even when human self-consciousness recognizes itself as co-constitutive with its circumstances, the understanding of those circumstances often leads to the conclusion that there is nothing that can be done. Capitalism sure can feel natural and normal, yet there is nothing natural about me being able to understand my computer’s value in terms of cups of coffee. Plot twist: we made up the concepts of money and exchange value. Only when one understands the dialectical truth — that one’s circumstances, and thus one’s very identity, are a direct result of human history and culture, and thus are not “natural” but malleable to human will — does emancipation peek from under the far-off horizon.

Where’s the art?

Yeah, I know, this publication is about art. I’m getting there. My point about the self being the self, the circumstances the self is in, and the self’s understanding of those circumstances, is ultimately about the potential of art. The art object (and I take “object” here to be a conceptual object, meaning a dead white man’s symphony, a b-boying/girling competition, or even a mundane reproduction of flowers in a vase could all count) has a certain auratic power, however weak, that can run a hairline crack through our well-worn patterns of perception. This is because when we take something as art, when we perceive it as art, as something distinct from the quotidian, it becomes a new part of our circumstance, and thus a part of ourselves and how we understand ourselves. This means that art can disrupt our everyday perceptions and lead to new understandings of our circumstances and our selves. Before the art object, human subjectivity has a chance to become anew.

This is, in part, due to the fact that the experience of most art objects is an experience of the human power to produce and reproduce the world. It is a concrete moment of that very human capacity. We forget, though, that our institutions, everyday objects, social relations, work patterns, languages, etc. are also examples of this human capacity. Art can help us to understand how the very components of our reality bear a shocking resemblance to something radically and dramatically human. Through the dialectic of art, the seemingly immutable background of Being begins to stir.

To what purpose, then, might we put art? Could it really be a means of waking us all up to the socially produced nightmare of material wealth disparities, the inane norms of labor, and the unnatural depravity of consumerist desires? Or must it be resigned to some pedagogical idealism, rendered impotent by the very circumstances in which it is produced? What the hell would world-changing art even look like? Sound like? Feel like? IDK, but maybe I’ll write on that next. It just seems to me that if somehow more folks understood the I and the circumstances for what they are, then they might not stay that way.

New Year, new me — amirite?

[1] Have I read Michael Taussig’s The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America? Yes. Was it years ago? Yes. Please forgive any sins committed in my crude recounting off the top of my head.