Picture a dimly-lit cocktail lounge with faded jade green walls and a polished antique wooden bar — well-maintained yet unpretentious, making no attempts to cater to a particular crowd. The room is filled with people of various ages and backgrounds, and an eight-piece band holds court from one corner. The atmosphere is ebullient, buzzing with the sounds of genial chatter, glasses clinking, dancing feet shuffling. Hot jazz reminiscent of the 1920s and 30s emanates from reeds, brass, strings, and drums. One tune ends and the conversation rises as the musicians re-arrange their charts for the next number. After a moment, the din is interrupted by a thrumming rhythm section accompanied by brooding long tones from the horns. An air of anticipation ripples through the crowd, and a clarinet trio rips deftly into a wailing minor chord with a glissando that could part the heavens, followed by gritty, audacious trombone interjections that bring everyone back down to earth. At the center of the crowd, surrounded by shuffling, twirling, and swiveling pairs of swing dancers, another group has coalesced into an exuberant interpretive dance, waving their arms about without a care and ensuring that no one takes themselves too seriously. For that moment, everyone in the room is completely present, unencumbered in the shared experience.

Collective effervescence, social resonance, brain chemistry, entrainment, flow — there is a wealth of research exploring this phenomenon and the scientific explanations for its power. Whatever you call it, or however you explain it, those who know know. It’s something you experience with your whole person. Boundaries between body, mind, and spirit dissolve. Barriers between self and other become transparent. Musicians and audience are intrinsically intertwined. These situations present us with a microcosm of society as a whole, showing us how it feels in our bones to be independently interdependent.

Collective musical experiences like these inextricably combine thought, emotion, and sensation, shifting us effortlessly into a flow[1] state. There are several mechanisms at play, and the research on this phenomenon is multi-faceted and ever-evolving.[2] From a neurological perspective, group music-making can stimulate an interplay between the conscious and autonomic nervous systems, allowing participants to shift into a more balanced state and “get out of their own way.” Additionally, when we make music together, our brains release “a cascade of neurohormones” known as the social bonding chemicals. According to a 2014 study, both playing and hearing music engages the “endogenous opioid system” and sends oxytocin, vasopressin, dopamine, and serotonin coursing through our brains and bodies.[3] In a scene like the one described above, there is no distinction between thinking, sensing, and feeling. Cognitive, tactile, and emotive functions, which are all vital to musical participation, come together in “somatic integration” — an embodied selfhood.

The problem is, we are not generally taught how to cultivate this embodied selfhood in our Western education system — either as it relates to music-making holistically, or in terms of our interactions with others. The importance of approaching music from a place of somatic integration is rarely discussed in traditional academic programs, nor is it a common part of discourse in the professional music world. The focus is on the product, not the person. Everything is oriented toward achieving a measurable external goal, rather than organizing an internal environment that allows for freedom of expression and, incidentally, the creation of authentic, moving sounds. Much of the writing on and application of practices of embodiment (or somatics) in relation to music is centered on body awareness in order to avoid injury, improve technique, or manage performance anxiety. But what about the way we learn, internalize, or simply experience music as a performer, listener, dancer? What about our humanity? As a field, we need to prioritize personhood, or as David Elliot writes in his seminal text Music Matters, “a dynamic, social, interpersonal, empathetic co-construction process, not a fixed bundle of never-changing thing.”[4]

“Somatic integration” or “embodiment” refers to the dissolution of boundaries between the body, mind, and spirit and the notion that the body, its movements, habits, and holding patterns are an intimate reflection of the activity of the mind. This way of being extends far beyond the physical, technical, or psychological and can fundamentally change the way we interact with the world around us — both consciously and subconsciously. This is especially important in the current moment, given our cultural obsession with productivity and the constant level of external distractions by an over-abundance of media. Group music-making can be a catalyst for this embodied awareness and can contribute to somatic integration due to its effect on the nervous systems of all participants; and from an integrated self, new connections with others necessarily begin to grow. One’s somatic experience begins to stretch beyond the confines of the self and into the world. Somatic Psychologist John Rowan’s holistic listening comes into play here: “Instead of grasping and grabbing the world, we find ourselves allowing the world to come to us, so that we can flow out and become that world, losing our usual boundaries…We can then suspend thinking and be aware…in the ever-flowing present.”[5] The culmination of these factors in collective music-making is a sort of social-somatic resonance. And when that all comes together in a way that feels transcendent, it becomes collective effervescence.

There’s another fascinating attribute of shared musical moments known as “entrainment.” Duke Ellington recognized this before there was a scientific name for it and alludes to it in this passage describing an encounter with the great stride pianist, Willie “The Lion” Smith: “A square-type fellow might say, ‘this joint is jumping,’ but to those who had become acclimatized — the tempo was the lope — actually everything and everybody seemed to be doing whatever they were doing in the tempo The Lion’s group was laying down. The walls and furniture seemed to lean understandingly — one of the strangest and greatest sensations I ever had. The waiters served in that tempo; everybody who had to walk in, out, or around the place walked with a beat.”[6]

In its simplest terms, entrainment refers to the synchronization of rhythms. This synchrony is incredibly universal. It can occur all the way from the sub-atomic to cosmic levels of nature and can be facilitated through every type of interaction from mechanical, to chemical, to gravitational, to electrical.

Interpersonal synchrony, or the synchrony between two or more people, provides another layer of this social-somatic resonance to explore. When a group musical episode is “in sync,” everyone in the space — musicians, listeners, and dancers — experience entrainment in the rhythms of their brains and bodies. According to neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas, this can include heart and respiration rates as well as certain brain wave patterns. Of course, physical objects play a part in this resonance. For example, if you place a number of pendulum metronomes on a moveable platform and start them all out of time from one another, the mechanical energy transferred through the motion of the platform will cause them to synchronize in a matter of seconds (see the video linked above). In the same way, music vibrating through a space provides somatic platform for interpersonal synchrony. Viskontas also explains: “When you’re moved by music, we see levels of the attachment-hormone oxytocin increase. People who sniff oxytocin before they play together are more in sync rhythmically. For all of us, these neurochemicals make us more attuned to the signals we use to understand each other’s behavior.”[7]

Of course, there are a great deal of sound-related and cultural variables to explore in this discussion. The examples referenced thus far share common threads of improvisation and spontaneity, both closely associated with jazz music and the dances that tend to accompany it. Instances of these experiences can be found across cultures and genres, and arguably this phenomenon is most pronounced in situations which allow musicians and audience members the freedom to express themselves with movement and sound. In fact, in many instances across the globe, music is a means to an end — many cultures don’t even label this kind of sound-making as “music.” While some find it difficult to let go of the romantic notion of “music-as-we-know-it” as a universal, I believe it’s far more powerful to see our humanness itself as the unifying thread. The element that seems to be more universal isn’t actually the music but rather the “transcendent togetherness” achieved through collectively “organized sound.”

So, what about collective effervescence in “classical” or “Western art music” contexts, in which the music itself tends to be revered to a fault for its relentless pursuit of perfection in performance, widely considered to be the end rather than a means to something greater, and where the social norms around taking it in are much more strict and prescribed?

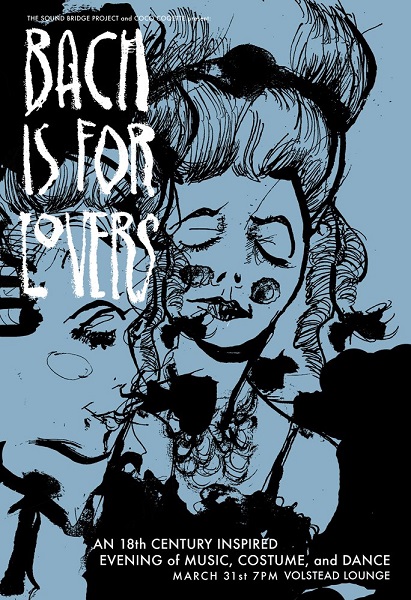

One answer could be to remove some of those structures, reset long-engrained expectations, and place that music in a different setting. Several years ago, “Alt-Classical” consortium, The Sound Bridge Project and local wigmaker Coco Coquette presented a concert and eighteenth-century costume party called “Bach is for Lovers.” Our idea was to place “classical” music in non-traditional spaces in hopes of removing some of the elitist trappings of the concert hall and make it more intimate and accessible to a wider audience, as well as introduce costumery to create an all-encompassing, participatory experience. We wanted the audience to feel as if they a part of the happening, instead of being silent witnesses trapped in darkened rows of seats. And we wanted them to feel as if they could be themselves — to be comfortable in their own skin. The venue was a small hipster dive bar with brocade wallpaper and shabby antique furnishings. The evening opened with J.S. Bach’s 3rd Brandenburg Concerto. The sense of novelty and delight was palpable as people in various states of frippery milled about the room sipping cocktails and batting false eyelashes at one another. At one point, the first violinist played a particularly flashy passage with a jubilant flourish and the crowd erupted into applause, hooting and hollering as if they were at a rock show. That moment was an unequivocal instance of collective effervescence. It’s possible that the safety of a casual environment, along with the whimsy of the costumery and the cognitive dissonance of such traditionally “refined” music performed in an “unrefined” setting, allowed for a less cerebral and more embodied experience, and thus lent itself to greater social-somatic resonance.

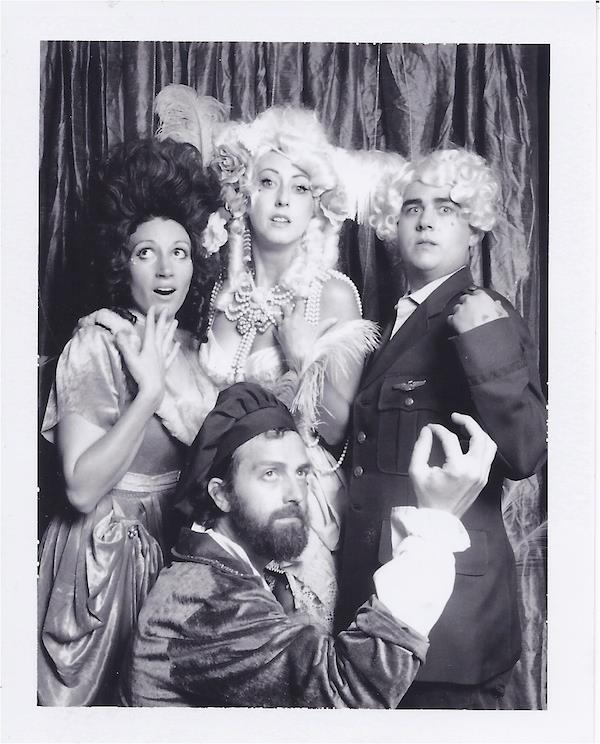

Photo from a “wig party” where attendees (including L. Gould, center) played live musical chairs, a reference to a scene from Amadeus (1984).

This is not to say that collective effervescence isn’t possible in a concert hall. There is certainly an argument for the sublime beauty of music taken in without distraction and, for example, the subtle yet powerful collective experience of the anticipatory hush after the second movement of a symphony. But prim, reserved silence was not, by any means, the atmosphere at concerts in the eras when much of that music was written; quite the contrary. If audiences were encouraged and allowed to respond freely to the music in any way that they were moved — with quiet contemplation during tender moments and thunderous applause to celebrate the exhilarating or bombastic — perhaps there would be a resurgence of enthusiasm for those types of performances.

It seems important to mention, also, that instances of universally experienced collective effervescence can be elusive. Live music experiences sometimes fall flat. Any number of factors might block one’s access to that seemingly otherworldly “sublime flow” or make it difficult to connect with others. But as it is with any other creative discipline, consistency is key. The more time we invest in building soundscapes with others — at any level of participation — the more readily we may be able to tap in to that social-somatic resonance. Additionally, as musicians, we might feel as if we’ve missed the mark in a given performance, but someone in the audience might experience it differently. Maybe it was life-changing or live-saving for them, and that makes it worthwhile. Part of our work as musicians is to allow ourselves to actually suspend judgement when we’re on the bandstand, or in the audience, and simply relish the exchange of intangible gifts that ensues.

In fact, this point elucidates the way in which the conceptualization of collective effervescence has continued to evolve. Nineteenth-century sociologist Emile Durkheim coined the term to distinguish the sacred from the profane, but modern-day scholars suggest that some level of collective effervescence can be found even in everyday activities. In their article “Creating the sacred from the profane: Collective effervescence and everyday activities,” Shira Gabriel, et. al. argue that “simply being with others in a group event can bring a sense of connection and sacredness that can improve the quality of life because human beings are fundamentally and inextricably social.” The authors tested this hypothesis across nine different studies, utilizing eleven datasets, and 2,500 participants of diverse gender, ethnicity, and age groups, and found that “the current research is consistent with a view of humans as fundamentally social creatures that find rewards just from being near other people even when we are unaware of the nature of the reward or the reason behind it.” Durkheim spoke of collective effervescence in terms of its connection to the sacred, but it seems that a broader definition for what constitutes “sacred” would be more fitting. Perhaps anything could become “sacred” under these circumstances. After reviewing the results of their study, Gabriel, et. al. concluded that collective effervescence may effectively “take that which is most common and seemingly least special and elevate it to a level that brings meaning and connection to life.”[8]

Of course, it would be disingenuous to ignore the state of the world at this moment, nearly 19 months into a pandemic that has put most live music performance on hold, not to mention the additional layers of socio-political turmoil, extreme isolation, and loss upon loss. Humanity is experiencing very real trauma and grief, both individually and collectively. We need social resonance and critical inclusion to heal, and we need tools that help us move forward, to act from a place of empathy and care. These moments in which we transcend our thinking selves and connect with others can offer a respite from the pressures and hardships of daily life, a way to process pain and trauma, or even simply an opportunity to tap into our creative streams without inhibition. They can also help us to find the wonder and delight in our worlds. As Julia Cameron writes in The Artist’s Way, “The quality of life is in proportion, always, to the capacity for delight.”[9]

In contemporary Western society, the value of music is often couched in the technical and centered around the individual. The virtuosic prowess of a jazz soloist, the power and clarity of a pop singer, and the passion and flair of a symphony conductor are all perfectly valid sources of inspiration and awe, yet, our considerations rarely take in the sum of those parts that we find so stirring, let alone the vital role that the audience plays in the encounter as a whole. This gestalt[10] that results from the interactions both within and among musicians, listeners, and even bystanders is what gives meaning to the experience. Musical gestalt facilitates collective effervescence, which clears the way for presence; and presence clears the way for wonder, delight, catharsis, and healing.

It’s no coincidence that music accompanies so many instances of shared emotional pinnacles across cultures. In some ways, the importance of these collective music experiences has been thrown into even sharper relief by our responses to the slow, cautious return of in-person performances after a long, traumatic global hiatus. Consider Michael Barnes’ reaction to the first orchestral concert he attended in person after 15 months with no live music. Of all things, it was the unexpected sound of the maracas in José Pablo Moncayo’s “Huapango” that struck him most strongly: “Like a rattlesnake’s warning, this tingling sound ricocheted through my nervous system, reminding me that certain responses to orchestral music cannot be duplicated by listening to recorded or streaming versions of it.”[11] This past week, a group of my friends organized a “Pop-up Swing Picnic” in a public space which conjured some of that magic as well. Our jazz quartet provided unamplified music, soft enough to hear the dancers’ feet shuffling across the pavement but projecting enough to be heard throughout the park. Passersby stopped and lingered to enjoy a scene they were not expecting to find on their evening walk. Listeners expressed gratitude to us for bringing people together in a time when we feel so far apart. One person shared that it was the first live music they’d heard in two years and that being a part of it was “the coolest thing they’ve ever done.” We may have to be extra creative and flexible until it’s safe to gather in close quarters with wild abandon again, but until then, we must find connection where we can so we can move forward and start to heal. Maybe this unintentional reset will provide us with a renaissance of enthusiasm for the collective experience that comes with live music. And maybe seeking out these moments of collective effervescence will help us connect with our humanity and what it means to truly be alive.

Further Reading:

Blacking, J. (1969) ‘Expressing Human Experience through Music,’ in Byron, R., ed. Music, Culture, & Society: Selected Papers of John Blacking, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Blacking, J. (1973) How Musical is Man?, Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York: HarperCollins.

Elliot, D. (2015) Music Matters: A New Philosophy of Music Education, 2nd Ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Graves, J. (2005) Cultural Democracy: The Arts, Community, and Public Purpose, USA: Board of trustees of University of Illinois.

Hartley, L. (2004) Somatic Psychology: Body, Mind and Meaning, London: Whurr Publishers Ltd.

Higgins, L. (2012) Community Music in Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Small, C. (1998) Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Vuilleumier, P. & Trost, W. (2015) ‘Music and emotions: from enchantment to entrainment,’ Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Issue:The Neurosciences and Music V.

Walsh, R. (2011) ‘The Common Basis of Narrative and Music: Somatic, Social, and Affective Foundations,’ StoryWorlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, Volume 3.

End note: Special thanks to the Editors, Dani and Elisa, for their insightful questions and feedback through the process of writing this article. Their input was invaluable in pushing these ideas toward a more focused, critical edge, and their encouragement bolstered my confidence as a writer and thinker.

[1] This refers to the concept of flow as presented by Csikszentmihalyi in his book of the same name on The Psychology of the Optimum Experience. According to Csikszentmihalyi optimum experience or flow occurs when aptitude and challenge are in balance toward absolute enjoyment of the event, and arguably “embodiment” as well.[2] These ideas draw upon research from a variety of disciplines: Neuroscience, Psychology, Somatics, Music Education, Ethnomusicology, etc. See further reading section for more details.[3] Kevin Berger, We’re More of Ourselves When We’re in Tune with Others, Nautillus: Science Connected, July 25, 2019.

[4] David Elliot, 2015 Music Matters: A New Philosophy of Music Education, 2nd Ed, New York: Oxford University Press, 161.

[5] John Rowan,1985 quoted in Linda Hartley, Somatic Psychology: Body, Mind and Meaning (London: Whurr Publishers Ltd. 2004), 194.

[6] Duke Ellington, Music is my Mistress (Garden City: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1973), 90.

[7] Kevin Berger, We’re More of Ourselves When We’re in Tune with Others, Nautillus: Science Connected, July 25, 2019.

[8] Shira Gabriel, Esha Naidu, Elaine Paravati, C. D. Morrison & Kristin Gainey (2019): Creating the sacred from the profane: Collective effervescence and everyday activities, The Journal of Positive Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1689412.

[9] Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way, (New York: Penguin, 2016), 53.

[10] Gestalt is a term for a whole, perceived as greater than the sum of its parts.

[11] Providing a link to this video is a little ironic, since the point being made is that the recorded versions pale in comparison to the in-person experience. Perhaps readers will at least enjoy this recording, and then try to hear it live someday to feel the difference for themselves.