It was my graduation as a music major from Rich White Kids Who Drive Subarus College in New England, where I was sent from middle-class suburban Arizona to fulfill an American Jewish assimilationist dream.[1] In some real sense, I went to RWKWDS College to learn the ways of those who drive Subarus and find myself a well-to-do intellectual girlfriend whose father could teach me to sail.

So it’s graduation weekend, and there’s a choreographed sequence of events that somehow involved my klezmer trio — Gefilte Dog — playing in the corridor outside the art gallery. And that’s how my parents came around the bend to find me, with an accordion strapped to my chest, belting “My Yiddishe Mamme.” My voice was wailing and lilting and cracking in the style of the great cantors my dad played for me on the Victrola on special occasions when I was young; my sound and movements were channeling the Eastern European-immigrant lay cantor on Yom Kippur at the small synagogue where I got bar mitzvahed (which my parents called Congregation Pray-and-Save), embodying his spirit as he cried out the high notes of sacred sound. I was losing myself into a state of ecstasy. It was a theater of sincere irony, which is more or less how we’ve always done Judaism in my family. It was high camp — a show of in-your-face Jewy-ness with an unmistakable whiff of secreted faggotry. It was transcendent.

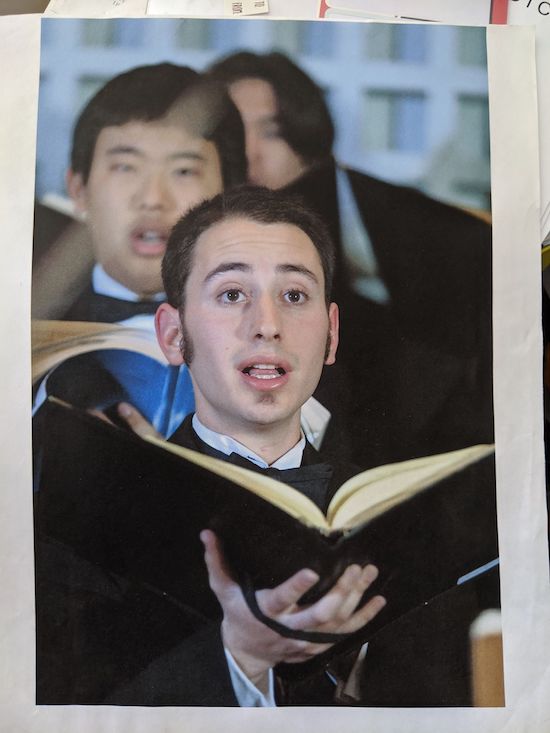

Let me say a few things about my singing: I joined choir in high school at the urging of an acquaintance — they needed boys — and it became a refuge for me as a gay boy in the frightening world of high school, as it was for others. And I was good at reading music because I grew up taking piano lessons. We did all-state and regionals and whatever else one did with their premier public high school choir. We were called the Choraliers. At some point, I’d wanted to go to the state university to study music education and become a choir director. At RWKWDS College, there was no music education major, although a friend did double-major in education to make a career for himself as a music teacher. We had a big college choir that performed what were termed “masterworks” with an orchestra (I had a few solos as a baritone). In addition to singing with the college choir, I took weekly voice lessons and sang in (and for a couple years directed) an a cappella group that rehearsed five nights a week, toured internationally, and performed in tuxedos for Republican presidents, etc. And I played and sang in the gamelan for a short period.

But as a college student studying voice, it was in my klezmer band with a couple friends that I had the most transformative and meaningful musical experiences and indisputably performed at my best as a musician. Through my performance, I was exploring both the past and the future — imagining myself channeling a sound and a feeling that belonged to my ancestors, while also enacting and exploring the possibilities of my own future personhood. My sounds and movements were an exploration of stereotypes about Jews and Jewish masculinity, of the burdens and opportunities of sounding Jewish, and of the physical and aural experience of a kind of vocalization that could be described as ecstatic, transcendent, or transformative.

On a related note, transformation is the word of the day in music studies in higher education, not in the sense provoked by ecstatic musical experience but rather in an institutional one. How do American music institutions approach the kind of cultural change that is necessary to become truly inclusive? At the school of music where I teach, transformation has been a key concept in faculty discussions over the past two years. In this article, I draw inspiration from the work of scholars whose voices are shaping the current conversation about institutional transformation. Specifically, I am engaging those works of scholarship that were shared among a task force of my colleagues — twenty-five faculty members strong — to study race and bias in our core curriculum and generate recommendations for reform (for transformation!).

Foremost in our discussions was Philip Ewell’s theorization of the discipline of music theory itself, which, he argues, is structured by a “white racial frame” (Ewell, 2020, drawing on Feagin’s term, 2006).[2] Many American music professionals continue to believe music theory is a kind of positivist science or a cousin of mathematics, related to the fields of physics and engineering. If it is (and in my view, given the vast diversity of musical systems and logics on our planet, I would argue that it isn’t), it ought to be subject to the same kind of interrogation inherent to the growing field of science and technology studies. We are only now actively confronting the workings and implications of epistemological hegemony in corners of knowledge production that have previously pushed such conversations to the margins. As Ewell demonstrates, we cannot deny that knowledges themselves have histories that cannot and do not exist apart from the complexity of life/experience/society.

While Ewell makes visible the epistemological and material whiteness of music theory, Loren Kajikawa teaches us that discourses within our music institutions surrounding notions such as “excellence,” “masterworks,” and “serious” music are rooted in exclusion and are structurally related to white supremacy — both reflecting and reproducing it.[3] As he explains, what our programs teach is whiteness — we offer access to whiteness, which in turn offers access to society. Such an investment in whiteness, he shows, derives from the historical relationship between whiteness and property ownership in the United States. A result of this particular investment is an exclusion of nearly all other musics in our music schools.

I think it’s important to note that whiteness is just one element within a matrix of cultural supremacy upheld by heterosexual Christian Western European (or Western European-descended) men. Moreover, the valorization of whiteness often connotes a valorization of the broader cultural values associated with it. What we are doing is reproducing Western European culture racially, spiritually, and through sound.

Finally, I turn to the voice of Danielle Brown, whose critical testimony rang loudly through the field of ethnomusicology (2020). For me, Brown’s work models the analytical and persuasive power of ethnomusicological authoethnography. Her testimony demonstrates how both institutionally and intellectually “ethnomusicology remains a colonialist and imperialist enterprise,” and so she teaches us, “people of color must be at the forefront of telling their stories until some sort of equity is reached.” Her book East of Flatbush, North of Love: An Ethnography of Home (2015) centers on the Trinidadian neighborhood in Brooklyn where she grew up, which happens to have been the Jewish neighborhood where my father was born and raised in the ‘30s and ‘40s.[4] While reading her book, I couldn’t help but wonder about the sounds of my father and the world of his childhood in some of the spaces she describes, which of course have transformed over time. It is because of Brown’s call that my mind has turned to the music of my own upbringing.

I am writing this essay to add my voice to the conversation about the nature of musical exclusions and violences experienced by those of us whose musics and selves are minoritized by institutionalized American school music. The tagline of this essay refers to a term I have heard used by some of my colleagues; in their usage, “meaningful musical experiences” are something important that only traditional large ensembles can offer a music student. As an ethnographer, I understand this discourse of “meaningful musical experience” to connote a cultural value related to the performance of a particular music with a particular history and a claim to that music’s universal superiority in terms of the sensory and transformative experience of its performers and in terms of the attributes of the musical sound itself. Such a reading suggests that if meaningful musical experiences are only attainable through the performance of works written either for the church or in the broader style and tradition of music written for the church (by which I mean all Western art music), then they cannot be achieved through the (at times virtuosic) solo or group performance of ecstatic sacred music from other religions, nor from other meaningful musics, which all musics are. Which leads me to my main point:

Although school choir was a space that included me — indeed, harbored me — as a gay boy, it was also a space that very explicitly excluded me as a Jewish person. School choir, in my experience, promoted violence against Jewish musical epistemologies and (only somewhat indirectly) against Jews in general. In this article, I offer an autoethnographic study of singing in two cultures, written from my scholarly perspective as an ethnomusicologist — that is, an ethnographer of music — thinking from the interstices of sound studies, voice studies, and global music history. I should note that I do not consider myself a scholar of Jewish music. My aim here is to illustrate how relationships between singing and the achievement of “meaningful musical experiences” vary from singer to singer, depending upon the singer’s background and the cultural meaning of the music being performed. More directly, I am refuting two claims made by my colleagues: (1) that only large Western-style ensembles can provide students with meaningful, excellent/virtuosic, and transformative musical experiences; and (2) that school choir is a safe space for queer students. Because school choir writ large is exclusionary in multiple ways, it is not safe for everyone. At the root of this article is a critique of the way in which a Western European cultural matrix has become normalized in complex ways in American school music contexts.

A note on sound and assimilation

There’s too much to be said about sound and loss for Jews.

I think about Jews who work to lose the sound of New York in their voices. And I think about those of us who invariably (but not inexplicably) sound to others like we’re from New York when we’re from places like Arizona.

I wonder about what the Jewish congregants in Pittsburgh were singing when their synagogue was attacked by a gunman in 2018. What did that music sound like? Were they singing the same melodies sung by my great-grandparents who also lived in Pennsylvania?

There’s the story about Jews singing on the train to the death camps. One man — a cantor and composer — began singing about his belief in a utopian future. It’s a melody that starts low and then gradually and almost reluctantly winds upward. Everyone in the cattle car — they were packed together like livestock — began singing with him.

That song survived the Holocaust because of a boy who jumped from the train at the cantor’s request (actually, two boys jumped — one didn’t survive the jump) to teach the melody to the composer’s rabbi, who had escaped to New York. It’s a song Jews still sing, and it’s a story about the power of singing that Jews still tell. You can hear the song, “Ani Ma’amin,” performed by a cantor and Holocaust survivor named Moshe Taube (1927-2020):

The topic of Jewish music is too broad for this article, but I’d like to offer a few clarifications: Jewish identity, like all identity, is a construct. There are many people around the world who recognize themselves as Jewish and many musics that are understood as Jewish by their practitioners. My focus here is on my own experience as an Ashkenazi (Germanic) Jew raised in suburban Tucson in the 1980s and ‘90s, a period in my life in which the practice of my Jewish religion and my self-recognition as a Jew were particularly central to my way of being in the world.

Cantorial knowledge

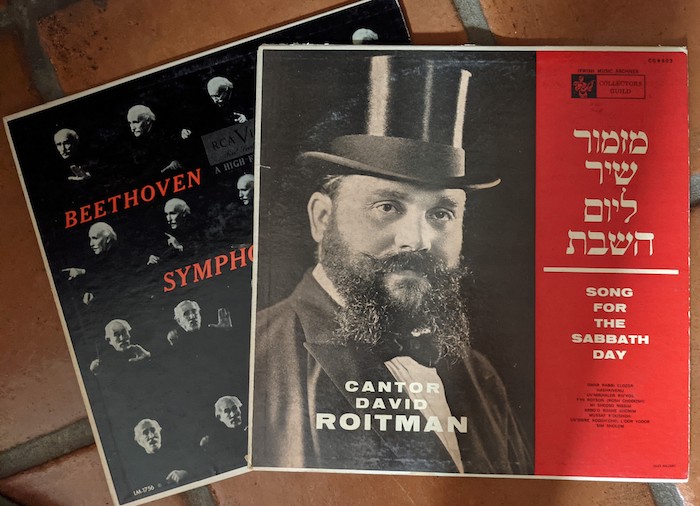

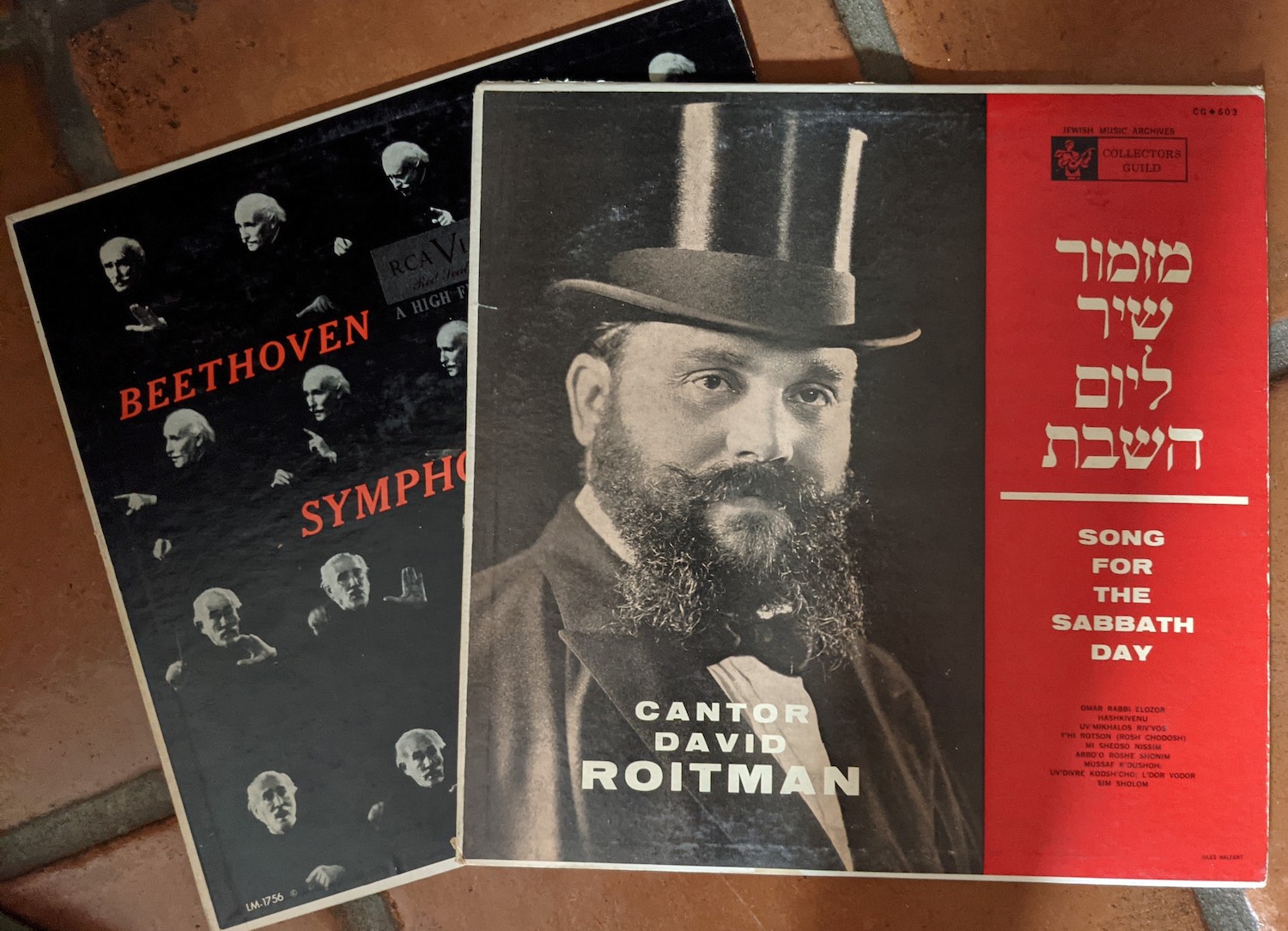

My paternal grandfather was a cantorial soloist at his synagogue in Long Island. He died young — in his early fifties — so I never got to hear him sing. What I know about him is that he loved classical music, particularly the Arturo Toscanini/NBC recording of Beethoven’s 9th, which I’ve always imagined him listening to while smoking a pipe. And he sang cantorial solos at the synagogue. He had a three-ring binder with his name embossed in gold on the front that he used for this purpose. My father gave it to me when I was in college, and I used it to keep the music for my klezmer trio. I thought of him every time I performed the music it held.

Jewish cantorial singing is a highly technical virtuosic vocal art. The cantors I grew up hearing possessed not only knowledge of technique and a large repertoire of melodies, but also knowledge of Ashkenazi Jewish music theory (as well as Western music theory). Ashkenazi Jewish music theory offers an interesting contrast with Western music theory because it entails — largely but not exclusively — the pitches of Western musical systems and employs harmonic accompaniment while still functioning within a different musical logic. Ashkenazi Jewish music is modal. The so-called synagogue modes, also referred to as shteyger or nusach, connote not only a collection of pitches but also a set of expectations and rules governing (oftentimes microtonal) ornamentation, melodic motion within the mode, and liturgical and temporal context, functioning much like other modal musics. Cantors spend many years studying the modes to attain skills as improvisers.[5] One important feature of modal music is that it allows for regional, local, and personal variation, and indeed hyperlocal variation within the system is characteristic of Ashkenazi Jewish music theory.

Ashkenazi Jewish music is heterophonic music that has been layered with Western homophony, but that musically doesn’t necessarily follow the rules, expectations, or desires of Western tonal harmony.[6] Since the Enlightenment, and the related assimilationist Reform Movement, Ashkenazi Jewish cantorial music has included multi-part choral arrangements for performance alongside cantors in larger, wealthier synagogues. If this music sounds harmonically unsophisticated to your ears, it’s because it is modal music with chordal accompaniment rather than tonal harmony. A listener with knowledge of the modes, however, would find interest in the choices made by the performer.

Ashkenazi Jewish music exists simultaneously in two systems of musical notation: Western notation and Jewish chant notation called te’amim (Hebrew) or tropes (Yiddish), which are diacritical markings surrounding words in a written text much like Medieval neumes. Even today, Jewish American children who go through the bar or bat (b’nei) mitzvah process typically learn cantillation, the reading and chanting of te’amim or tropes in sacred texts.

Cantorial music — chanting, in particular — is highly improvisatory. Like all musical improvisation, cantorial improvisation requires an intimate knowledge of musical tendencies, procedures, and histories/meanings and is a vehicle for both personal and communal expression. Listen to Yossele Rosenblatt (1882-1933), arguably the most famous cantor in modern Jewish history, sing “Misratze B’Rachamim (Selichot Prayer).” Note the microtonality in virtuosic melismatic passages, the sobbing technique, and the overall expressive quality.

About a century ago, many Jewish American cantors, such as Rosenblatt, were superstars in their communities.[7] This era is sometimes referred to as the golden age of cantorial music, and I grew up hearing about these vocalists referred to as the Great Cantors. My father still has his father’s 78s of the Great Cantors. These singers were at times considered virtuosic by Western art music standards as well, as they were sometimes also professional opera singers, some of them well regarded. This is in every sense virtuosic and profoundly expressive music, and it is a style of singing I grew up hearing not so much on records but in synagogue, where knowledge was passed down through cultural practice from one generation to the next.

Judaism was always about singing for me

Judaism was always about singing for me. Singing the prayers before lighting the candles. Singing with the congregation on Saturday morning. Learning to read tropes. Singing the Torah and haftarah portions at my bar mitzvah. Singing around the table on Passover. Singing at Jewish summer camp. Singing at Sunday school. Everything we did was a lesson in Jewish musicality.

Being Jewish has always felt bigger than singing — being Jewish when and where I was raised involved Adam Sandler and Mel Brooks and bagels and the art of expressing displeasure — but practicing Judaism was primarily about singing. I can still recall several haunting, heart-rending a cappella solo performances of Kol Nidrei on Yom Kippur at the synagogues we belonged to when I was a kid — four distinct cantors’ voices come to mind, each performance unique.

I attended Jewish parochial school for middle school, a choice that probably embarrassed my secular parents to some degree, and that in retrospect I made almost entirely because the sixth grade class performed a musical on the day I visited.[8] To my delight, there was lots of singing in Jewish day school: we had daily prayers in the morning in the library, when we’d daven and lay t’filin together. And there were Friday afternoon prayers when we’d welcome the sabbath by singing and lighting candles. Most of our singing was in Hebrew, although there were also songs and prayers in English and Yiddish, as well as a few in the ancient language of Aramaic. And there were the annual musicals, in which everyone in my grade performed and I always got big roles (my proudest was as an unlikely — short, Jewy, delicate — Gaston in Beauty and the Beast). Every day in the cafeteria we’d sing the prayer before lunch, and the prayer after lunch, and if I remember correctly, sometimes there was singing after the prayer after lunch, just for fun. Some of the melodies we sang were ancient, and we participated in a musical culture that supported countless variations within it and yet that maintained some kind of integrity, existing both within and apart from mainstream Christian society and its sound worlds.

The school’s Chassidic rabbi frequently led us in nigun singing, a practice in which you enter a state of ecstasy through singing a repetitive, often wordless melody.[9] Singing nigunim with a group of people is a deeply powerful experience of togetherness and timelessness and, for adults, can be particularly intense when vodka is involved. Some of the melodies we sang could have come from the not-too distant past of my ancestors in Skierniewice, Medzhibozh, and Kamianets-Podilskyi. Even the vocables sound Jewy to my ears: oy-yoy-yoy, boi-boi-boi,… The rabbi sometimes taught niguns in the context of allegorical storytelling about people with Yiddish names who lived in shtetls and who might have been my great grandparents. In his stories, a protagonist would encounter short melodies in the context of the narrative, and we would learn each one as it appeared. By the end of the story, we would have learned a multi-section nigun that we would all sing together, first slowly, and then gradually building in intensity and pace (and pitch) through a spirited feeling we called ruach until we were in a state of communal ecstasy — sweaty, raucous, and euphoric — our senses of self and time dissolved into a greater eternal togetherness. It didn’t always end that way quite so successfully, but sometimes it did.

Any goy who stumbled upon us singing like this would have found the whole thing very exotic. Maybe that’s why we had an armed guard outside the school’s gated entrance, which stayed locked when school was in session — this was in the early nineties. I remember multiple bomb threats (all explicitly antisemitic) made to the school when I was a student there. Practicing Judaism — singing as a Jew — can be dangerous.

On school choir for a Jew

Choral Christianity: Some recollections and facts, organized dramatically

I remember studying music history in college and feeling strange about having to memorize details about Catholic liturgy that were related to music in that they provided the structure and content of many of the musical works we were to study. I remember this never being remarked upon — no critical reflection on the connections between a historicized cosmology and a musical form. It was just something I had to memorize.

I remember noticing quite how many religious Christian classmates I sang with in choir, from high school through graduate school. Evidently, they also sang in church choirs. I came to understand that their church singing was exactly the same kind of singing we did at school — the same vocal technique, the same aesthetic, the same approach to homophony and polyphony and to tonality more generally, even some amount of the same repertoire. I remember heated arguments with some of these religious classmates in high school on long bus rides to choir competitions about whether I was going to hell because I was Jewish. Choir and church were their domains. They were concerned about my soul.

I remember getting hired to sing in an Episcopalian church where my choir director from college also worked as the music director. I remember getting up early on Sunday mornings with a few of my (Christian) friends from choir to ride with him out to the church, where I would sit in the choir loft in a robe and sing four-part harmony prayers I didn’t mean, about beliefs I didn’t hold. I remember feeling uncomfortable when I was the only one, or one of a few, in the choir loft who didn’t get up to take communion. And I remember feeling afraid that a congregant would figure out I was Jewish — I imagined they would judge me for being there for the money, see me as a greedy Jew. I remember finding the whole thing very stressful. I also remember noticing that being a music major — so unlike most other majors in this way — lent itself to finding work in the church industry. I remember a friend in graduate school pointing out to me that DMA students tended to be particularly busy with professional obligations during the Easter season.

I remember singing a piece with the honors choir at summer music camp — held at a regional university — about “the Jews” and the crucifixion of Jesus. I remember feeling squeamish about the piece, as beautiful as it was, and I remember feeling particularly horrified when someone read the English translation of the Latin text into a microphone before we began singing at our final concert. I remember how it felt as I sang those words. I remember thinking about filing a complaint. I remember thinking about the persistence of the myth of Jewish deicide, which has been central to the workings of antisemitism. Here is an English translation of the Latin text (and I encourage you to imagine a blonde-haired tenor reading it into a microphone with a voice full of drama and earnest intentions):

Darkness fell when the Jews crucified Jesus

and about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice

My God, my God, why hast though forsaken me?

My god, what kind of person would ask a Jewish child to sing this?

Relatedly, I notice that the large symphonic choir at the school of music where I teach currently has Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which is widely recognized as an antisemitic work, listed first in the promotional copy on the choir’s webpage to illustrate the kinds of musical works they perform. The website also says that the ensemble values “musical excellence and a belief in the ability of great choral music to transform the lives of those who perform and those who listen.” Indeed, it is a multiplicity of musical excellences and the uneven (and not inherently positive) nature of the transformations brought about by “great choral music” that I have been exploring throughout this article.

Choral music in the U.S. isn’t merely similar to Christian sacred music; it largely is Christian sacred music. And choral concerts take on many of the sensory and affective qualities of sacred ritual for certain people in the concert hall and on stage, and so choral concerts are church, intended to “transform” listeners through Latin texts and a Western European aesthetic of fine-tuning, tonal complexity, and vibrato. For those who insist that the American choral tradition writ large isn’t inherently goyishe, the Choral Public Domain Library (CPDL), a well-known online resource, includes 25,769 choral works categorized as sacred (and a look at subcategories clarifies that “sacred” refers specifically to Christian) and only 12,655 categorized as secular: less than half. Furthermore, the site lists zero Jewish composers in its search by “nationality or ethnicity” and offers no other mechanism for identifying Jewish composers or works.

We cannot forget that the history of Christianity’s global spread is also a history of people being compelled to sing in four-part harmony. Global imperialist capitalist expansion and Christian proselytism have always worked in tandem. Just as orchestral music education provides access to whiteness through music associated with the European elite (Kajikawa, 2019), choral music education provides access to whiteness through music associated with the church. I’m sure you know that scene in the African Queen with Katharine Hepburn wearing a big hat and seated at a piano trying to get a room full of black Africans to sing a hymn, an image that perfectly captures the integral correlation between the transformative mission of choral music and the colonial project. I think of my concerned friends from high school and wonder: Was she trying to save their souls by teaching them to sing in harmony?

The Hanukkah Song Problem

Hanukkah isn’t an important Jewish holiday.

It’s become an important Jewish-American holiday because of its proximity to Christmas. Most readers probably already know this.

Including a Hanukkah song in a Christmas concert doesn’t make the concert any less Christian, just as the song’s existence doesn’t make choral music as a musical epistemology any less Christian.

I think we can all recognize that nobody wants to perform or hear most Hanukkah songs. It’s not a great Jewish holiday for songs — primarily you’ve got the blessings when you light the candles, and then there are some children’s songs, most of which exist only because of, again, the holiday’s proximity to Christmas.

Some choir directors I sang with as a student had creative approaches to the Hanukkah Song Problem (the Jewish Problem?): one smart conductor programmed “Hallelujah Amen” from Handel’s Judas Maccabeus as a way of acknowledging the story of Hanukkah (thus acknowledging Jewish students) while staying within the musical tradition of the rest of the concert. I remember not feeling tokenized that year. Here’s another idea: a Jewish student could light the Hanukkah candles on stage (I’m sure they have LED menorahs for those concerned about fire safety) and the choir could sing the blessings.

Calling the evening a “Winter Postcard” doesn’t change the fact that we have come together in the early winter to celebrate the birth of the Christian god, the one killed by my ancestors, according to the choral repertoire. Christmas concerts are heartwarming and important for many people, for whom they commence the holiday season — and indeed the winter. For many students who sing in these concerts and audience members who attend them, they involve deep feelings of connection to one another, to oneself, and to the past, the present, and the future. This is particularly true for Christian students, whose holiday is being celebrated and whose musical heritage and musical knowledge is bringing everyone together in time through sound.

It’s interesting to me how the Hanukkah Song Problem made me acutely and uncomfortably aware of my Jewishness and the place of Jews in the larger world. And it’s interesting to me how it did so in the context of school and choir, contexts in which my religion and heritage should have been irrelevant (except for when I wanted them to be). Of all the contexts and situations I have experienced in my four decades of life, in none did I feel more aware of my minoritized and indelible existence as a Jewish person, as a Jew, than in choir (regardless of the choir, regardless of the conductor).

While we’re on this topic, I should tell you about the disastrous Christmas concert I produced at the private elementary school where I worked as a general music teacher and choir director for a year after college. I was uninterested in spending precious classroom time preparing students for a Christmas pageant when they could be learning to listen and improvise instead. For the sixth-grade performance, I had students perform short operas they had written themselves — silly, chaotic, expressive — rather than songs about Christmas. The show was such a debacle that an angry parent called the superintendent out of an important evening meeting in another building. I went home from the Christmas concert in agony, and I remember being sick all night.

Storytelling and other forms of Jewish expression

I’d like to return to my singing of “My Yiddishe Mamme” in college. I can still remember the feeling of performing it, sinking deep into the experience of time through sound with Mike on his guitar and Joe on drums, my voice exploding into the high notes at the end with a kind of cantorial wail, demonstrating many years of vocal study. Work I’d done on breathing, phrasing, posture, intonation, articulation, expression, listening — it was all relevant to my performance. And it was relevant despite differences in musical tradition. What if an education in music didn’t inherently entail an exclusionary framework?

I should stress that the American choral experience is exclusionary to students from many backgrounds, not just Jewish ones. There was a boy who sang in high school choir with me who had grown up in a notable family of mariachi musicians. I was rude to him because of his lack of familiarity with some classical music trivia. I failed to recognize his deep knowledge of mariachi as both a violinist and a vocalist, or the amazing fact that he performed in the orchestra, the choir, and the school mariachi, while also working as a professional mariachi musician outside of school. I suppose I was battling my own feelings of exclusion, profiting from my grandfather’s white assimilationist love of Beethoven, and by behaving as I did, I was claiming an insider position. I wonder about other violences he experienced in the universe of school music, violences that took on contours different from those I experienced.

This has been one of my main themes in this essay: There is no universal meaningful musical experience. White Christian students uttering the sounds of Bach and Britten are having an inherently different kind of meaningful musical experience than are students from other music-cultures. While Christian students of Western European ancestry are connecting with their own culture’s system of spirituality through the musical sounds of their heritage, the rest of us are voicing the sound of empire, some of us self-consciously.

You should know that my gay teenage self, who loved choir but not being Jewish in choir, would have been glad I wrote this — my testimony. It’s true that choir offered me a safe and meaningful space for self-expression as a white cis, gay boy and then as a young man. But the Western European cultural matrix that gets reproduced in our educational system is complex and multifaceted, as complex and multifaceted as music students themselves.

I hope you have read it as my modest contribution to the conversation about decolonization within music programs in the United States. My aim has been to offer another vantage point from which to observe the exclusionary workings of music within higher education and within insitutionalized American education more broadly. Just as I am interrogating the meaning of the dominance of Christians and Christianity in choir, we should all be asking about the meaning of the dominance of white people and whiteness in our music schools and departments more generally.

My simplest message is this: Students come into American music programs from many musical and cultural backgrounds, and they possess many musical knowledges. Not only do claims about the universality and superiority of the classical music we primarily teach, and its singular capacity for beauty and meaningful experience, sound inherently white supremacist to those of us aware of musical/sonic difference, but such claims are also directly hurtful to many students, whose developing senses of self are being violated and diminished by peers and authority figures who deem their heritage inferior and contemptible. Importantly, many of these same students — these musicians — are the ones who are most vulnerable to identity-based physical violence. This is my message. To those who aren’t interested in hearing it, my grandmother would have had a suggestion for you, which implied a relevant mode of listening: Vaksn zolstu vi a tsibele mitn kop in dr’erd.[10]

[1] A couple important points: First, not all Jews are white. Second, many American Jews, like Italians and other Southern and Eastern Europeans, came to be seen as white primarily in post-WWII America, initially thanks to repercussions of the G.I. bill, which excluded Black Americans and others who continued to be seen as racial minorities by mainstream white American society. See Brodkin, K., & Sacks, K. B. (1998). How Jews became white folks and what that says about race in America. Rutgers University Press.

[2] Ewell, Philip. “Music theory’s white racial frame.” Music Theory Spectrum 43, no. 2 (2021): 324-329.

[3] Kajikawa, L., 2019. “The Possessive Investment in Classical Music: Confronting Legacies of White Supremacy in US Schools and Departments of Music.” In Seeing Race Again (pp. 155-174). University of California Press.

[4] Brown, Danielle. East of Flatbush, North of Love: An Ethnography of Home. New Orleans: My People Tell Stories, 2015.

[5] See Judah Cohen’s wonderful and rich ethnographic study of Reform Jewish cantorial school (2009).

[6] See Tarsi 2013 for an interesting and brief study of the development of Ashkenazi music theory and its relationship to Western music theory. Tarsi, Boas. “The Early Attempts at Creating a Theory of Ashkenazi Liturgical Music.” Jüdische Musik als Dialog der Kulturen (2013): 59-69.

[7] For more, see Slobin, Mark. Chosen voices: The story of the American cantorate. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

[8] It was a stage production of Marlo Thomas’s feminist Free to Be You and Me. I associate the album with my maternal grandmother, who would play it for me when I was young. I particularly liked a song about a boy who played with dolls and another that said it was okay for boys to be sensitive. On the topic of Jews and musical theater, you might be interested to know — true story — that my first favorite musical as a little gay boy who loved musical theater was Oliver!, and my favorite number in that musical was the Jewish-sounding one in the minor mode performed by the antisemitic archetype (and child molester) Fagin with lyrics about valuing greed and theft. If you know the song, I encourage you to try singing its refrain (“you’ve got to pick a pocket or two”) to Yiddish-sounding vocables such as “daidle deedle yadda yadda,” etc. in your best version of a Yiddish accent.

[9] See Seroussi, Edwin. “Shamil: Concept, Practice and Reception of a Nigun in Habad Hasidism.” Studia Judaica 20, no. 40 (2017): 287-306.

[10] h/t to Dylan Robinson for his “strategy of refusal” (2020).

“Any goy who stumbled upon us singing like this would have found the whole thing very exotic.” I would say that it might not seem so exotic to those Christians who practice a more ecstatic form of worship. I’m thinking of both Black and White churches where the worshippers, through singing or speaking in tongues or some combination, get into the types of states of communal ecstasy that you describe. What might seem exotic to them is that women aren’t included in the community in this fashion.

I wonder about the use of the term “exotic” in both the article and this comment. My own interpretation of the use in the article would be both about musical idioms and the ecstatic, participatory nature of the practice. In that sense, yes, there is overlap with Christian practices you describe, but the musical idioms are distinctly different, which is an argument of the article generally.

Michael. Loved reading this essay. Your memories of THA brought tears to my eyes.

Wish I understood the musical side better. Proud to have been your…

Thank you, Morah Stefi!