The knowing self is partial in all its guises, never finished, whole, simply there and original; it is always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another.

Donna Haraway

At the end of my first year teaching harp at my current institution, I attended a faculty meeting, the purpose of which was to review curriculum and address declining enrollment. This was my first time meeting some of my colleagues, and the inherent awkwardness of Zoom didn’t help what was going to happen next.

At one point, I suggested a more inclusive curricular approach: Why do we continue to require students to study only Western classical repertoire when many of them will not, realistically, pursue a career of performing classical “masterworks”? Immediately, one of my colleagues set off on a lengthy tirade, bemoaning what he perceived as an ongoing attack on classical music’s status in the academy. He insisted that the role of the university music program was to uphold “great Western classical music,” and that while he didn’t mind his students exploring other genres, they had to do it outside of his studio.

Due to the precarious terms of my employment, I didn’t feel like arguing — I couldn’t afford to argue — with this colleague. He is tenured; I must re-apply for my position every year. So, I left my microphone muted, forcing everyone to be acutely conscious of the uncomfortable moment of Zoom silence. Someone commented pithily about “maintaining standards of excellence,” then changed the subject. I inwardly fumed.

This tension between my colleague and myself underscores some fundamental debates in post-secondary (Western classical) music performance education: the purpose of the teaching studio, how we view our roles as teachers in this pedagogical space, and the (philosophical) relationship between teacher and student. In classical music, post-secondary vocal/instrumental studio teaching relies on the paradigm of the “master” and the “pupil.”

This paradigm can be strictly pedagogical; however, oftentimes it also involves other hierarchical relationships, i.e., mentorship or even musical “parenthood.” In my experiences as both a student and a teacher, friendship rarely develops, often due to age differences or professional boundaries. Nevertheless, many music teachers recognize the pedagogical reciprocity between themselves and their students: “I learn from my students all of the time!” is a common utterance in this line of work. Throughout the many interpersonal nuances of the master-pupil paradigm, I have found that one characteristic persists: the implicit belief that the teacher knows best (or at least, better). This belief materializes not only through repertoire selection and assessment rubrics, but also through how students are instructed to interpret the music they learn, to evaluate others’ performances, to construct musical narratives, and to relate to other listeners. In short, “classical training” in music depends heavily on the student’s willingness to be molded and disciplined by the teacher’s authoritative knowledge. The ensuing status quo is a pedagogical culture that venerates mastery and those who achieve it, often leaving behind individuals who may not fit well within conventional teaching methods (due to being e.g., differently-abled or neurodivergent) or who make music for other reasons (e.g., ritual, community-building, therapy). The exclusivity of an education in classical music is deeply ingrained in those of us — including myself — who have gone through many years of it. Consequently, we must dig equally deeply to figure out why and how these asymmetries of power persist in our teaching practices.

First, re-thinking the master-pupil paradigm involves challenging our assumptions about the concepts of authority, objectivity, and experience. In my understanding, authority denotes the power to decide, to control; objectivity assumes a state of impartiality or of being outside subjectivity; and experience simply refers to the knowledge or skill gained by doing. Sociologist Claire Blencowe argues — via philosophers Michel Foucault and Hannah Arendt — that authority and authoritative statements “derive from inequalities of knowledge. [They] provide guidance, judgement [sic] or witness from the position of ‘knowing better.’” Subsequently, authority is deeply connected not to objectivity itself per se, but to the idea of objectivity. She continues, “The condition of authority … is not access to truth per se (nor necessarily to past foundations or a shared place) but is rather access to some of kind of ‘idea of objectivity’; an idea of impartiality and of reality. Objectivity is the essential outside of experiential knowledge.” Because authority constitutes such a significant part of the master-pupil relationship, we might begin to consider how (the idea of) objectivity also informs the power dynamic of that pedagogical relationship.

(12 five-star ratings on eBay! Only $44.00!)

In the arts, objectivity either is misunderstood or finds itself in a contradiction. On one hand, we are told in broad strokes that “art is subjective” or “art is about self-expression.” On the other hand, idealism has made its mark on artistic movements, namely in discourses on aesthetics or the nature of art. In classical music, German idealism (via Immanuel Kant) influenced entire bodies of repertoire and legacies of criticism; however, the idea that music is a “thing-in-itself,” discoverable and mediated by representations, likely did not come ex nihilo to Kant. Lest we forget, music was a member of Plato’s quadrivium, which included mathematics, geometry, and astronomy. In De Institutione Musica, medieval philosopher Boethius further codified the cosmological idea that music, like its mathematical cousins, comprises transcendent and intangible truths about the world. Boethius’s musical philosophy persisted after his death and deeply influenced later philosophical movements in Western art music. During the Enlightenment period, counterpoint, particularly strict counterpoint, was considered a deeply scientific practice. In the nineteenth century, discussions about “absolute music” relied on the “conviction that instrumental music purely and clearly expresses the true nature of music by its very lack of concept, object, and purpose” (Dahlhaus 1991, emphasis mine).

These historical discourses on the nature — the truth — of music are integral to classical music traditions, and in turn surface through the teaching of repertoire, interpretation, and musical sensibility. Appeals to objectivity consistently emerge in our pedagogical instructions: how to harmonize, bring out dynamics and articulation, or devise ornaments; what physical gestures are considered “tasteful” or “stylistic;” and, most importantly, what works and composers are deemed “masterful” or “genius.” When teaching, we may often refer to the “composer’s intent” and eschew ahistorical interpretations (“Don’t play Bach like that!”), as if musical integrity could disintegrate from the addition of a few extra flourishes. Most of all, polarizing phrases like “sensitive interpretation” and “brilliant musicianship” illustrate that objective critiques grounded in (Western) aesthetic ideals are very difficult to distinguish from authoritative gatekeeping.

I worry, however, that doing away with all notion of objectivity, in art and in society, creates a solipsistic free-for-all, in which we become so preoccupied with selfhood that we forget that each self is situated amongst others. On social media, for example, we witness extreme ideological fracturing fueled by aggregated self-interest, where “personal rights” supersede ethical accountability to communities. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve seen people around the world divided over issues of masks and vaccines, resulting in innumerable preventable deaths. Over the past few years in the United States, we’ve witnessed massive corporations prioritizing their “right to profit” over the safety of people and the environment, the struggle to build racial equity in a country founded on the sacralization of white freedom, and rising economic disparity and homelessness in the face of soaring asset markets. During the 2021 Canadian election, I watched how rhetoric of personal responsibility and freedom fueled the rise of the nationalist, anti-lockdown/mask mandate, anti-gun control, climate change-skeptical (unfortunately, the list goes on) People’s Party of Canada. These events underscore the problem that placing primacy on individual reality, in the attempt to humanize and dignify oneself, can just as quickly blur into the territory of the inhumane.

My point is, total subjectivity is not an effective antidote to the problems conjured by an authoritative objectivity, mainly because both involve turning oneself away from the realities and needs of others. Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas advocated for the face-to-face relation, through which one’s confrontation with the physically present other creates a sense of ethical imperative within oneself. When Levinas writes, “[T]he Other faces me and puts me in question and obliges me … the face presents itself, and demands justice,” (Totality and Infinity 207, 294) he presents the electrifying realization that an ethical life demands an ontology of radical contingency — simultaneously beholding, being beheld, and being beholden (to). Throughout my ongoing struggle to translate my past training as a classical musician into a more equitable and empathetic pedagogy, I find myself returning, repeatedly, to this idea of face-to-face. When I teach my students, I am literally face-to-face with them; and so, I am confronted by their otherness, their differences, whether they be cultural and educational backgrounds, professional expectations, and/or simply bodily shapes and sizes. Rather than choosing between a false binary of atomized difference (subjectivity) or universal truth (objectivity), we should entertain an alternative cosmology: a world unfolding — or made meaningful — as a reality of contingent differences.

In her essay “Situated Knowledges,” STS/feminist scholar Donna Haraway offers a new objectivity based on what she calls “particular and specific embodiment.” This phrase refers to the political and physical situatedness of bodies; my body, for example, was born in the Bay Area, to parents of Taiwanese extraction, who first immigrated from Taiwan to Los Angeles in the 1980s. I was assigned female at birth and continue to identify as female. I come from a family of teachers, but my father works in tech, so spending my entire childhood in Silicon Valley cultivated a distinct sensitivity to inflated real estate, cold weather, and the word “start-up.” Feminist poet Adrienne Rich calls these types of individual markers politics of location, but Haraway goes one step further by refusing to consider location as merely the texture of one’s subjectivity. Instead, she insists that epistemological outcomes are created by ontological location, or situatedness. Thus, knowledge is not the representation of a pre-existing, unchanged reality — what Blencowe referred to as the idea of objectivity — but it bears the particularity of bodies. Haraway further suggests that objectivity cannot be about transcendence, detachment, or truth; instead, it must be about recognizing the extraordinary partiality of the world. This version of objectivity is a collectivization of us, situated and fractured so that we learn how to “become answerable for what we learn how to see” (Haraway 1988).

For those of us who teach classical music, we must be more aware of and accountable to our ontological-epistemic locations, putting in the hard work of tracing lineages of knowledge and recognizing the where, who, how, and why in what we pass on to our own students. Becoming answerable does not always mean re-writing history, and it certainly does not mean erasing history’s most shameful parts that only serve to remind us that goodness does not come easily to our species. It does, however, mean confronting and taking responsibility for what we have done and learned, and embracing others’ epistemic fragments as companions, not antagonists, to our own ways of seeing and hearing the world. Sound — how we hear and reproduce it — is both knowledge and lived experience. So, when Haraway asks “With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”, I feel compelled to echo:

“With whose blood were my ears crafted?”

In recognition of my own partiality, I would like introduce one last theoretical idea — something I learned from Stó:lō artist/writer Dylan Robinson. In his ear- and eye-opening book Hungry Listening, Robinson introduces the titular phrase as a critique of a universalized aurality, which he identifies as actually quite situated in a settler-colonialist logic. Borrowed from the Halq’eméylem words shxwlítemelh (“an adjective for settler or white person’s methods/things”) and xwélalà:m (“the word for listening”), hungry listening “prioritizes the capture and certainty of information over the affective feel, timbre, touch, and texture of sound.”

Most, if not all, classical musicians are trained to be hungry listeners; we extract, detach, systematize, and categorize, defining musical aesthetics and creating musical meanings through these acts. Paralleling Haraway’s approach to objectivity, Robinson’s response to hungry listening is “critical listening positionality.” Using the term to address how non-Indigenous people should navigate Indigenous sovereign spaces and “sound territories,” he argues that settler-colonialist (i.e., Eurocentric) musical sensibilities are rooted in time, place, tradition, belief, and culture, not justifiable by any philosophical truth or ideal aesthetic.

Musicians often say the meaning of music is too precise for words . . .The imperviousness in the West of the many branches of knowledge to everything that does not fall inside their predetermined scope has been repeatedly challenged by its thinkers throughout the years. They extol the concept of decolonization and continuously invite in their fold “the challenge of the Third World.” Yet, they do not seem to realize the difference when they find themselves face to face with it—a difference which does not announce itself, which they do not quite anticipate and cannot fit into any single varying compartment of their catalogued world; a difference they keep on measuring with inadequate sticks designed for their own morbid purpose. When they confront the challenge “in the flesh,” they naturally do not recognize it as a challenge. Do not hear, do not see.

Trinh Minh-ha

Critical listening positionality’s key takeaway is its refusal of aesthetic hegemony and its presence in our listening practices. Historically, Western art music has sought to assert its aesthetic superiority through philosophical appeals to idealism and objectivity. Subsequently, Robinson suggests that this sense of authoritative knowledge fuels entitled ears: Eurocentric ways of listening become emblematic of “civilization” and enlightenment. However, critical listening positionality goes beyond merely criticizing Western art music. Ultimately, Robinson wants us to reflect on the knowledge we take for granted when we listen and the ways we are tempted — through claims of “knowing better” — to impose our own aural and aesthetic knowledge on others’ epistemic spaces. Critical listening positionality, like situated objectivity, requires individuals to recognize that impartiality exists only as an aggregate of partialities. One cannot, in good faith, insist on knowing (and hearing) best when their knowledge only ever grasps a small piece of the world.

Partiality, positionality, situatedness… this philosophical framing is difficult business in a society organized around authority — and even more so (in the Global North), the type of authority that stands for the idea of objectivity. If anything, my students look to me for guidance; they want, even expect, me to tell them the right answers. Certainly, saying “this is how you play the harp” — no questions asked — would be much easier for me than working my brain into knots figuring out how to explain the critical listening positionality of Handel to a nineteen-year-old university student (who is perhaps more interested in passing their jury than questioning why Mozart’s music is considered “sublime”).

However, the beauty and the challenge of studio teaching lies in its intimacy, in the privilege of time spent face-to-face. Each hour of lesson is not only an opportunity for me to share my knowledge; it also grants me the possibility of situating my own partiality and listening to others’. Rather than treating the studio as a biopolitical site, where bodies are disciplined according to an ideal, I like to think of my studio as a space in which we can reflect on the ethics of aesthetics (and the aesthetics of ethics) — a space for better understanding our bodies, how they have come to be, and where they can go. In such a space, knowledge does not enter and leave intact, but is broken, chipped away, augmented, and re-formed. It is, as psychoanalyst Philip Bromberg describes his therapeutic relationship with his patients, a space that is “uniquely relational and still uniquely individual; a space belonging to neither person alone, and yet, belonging to both and to each.”

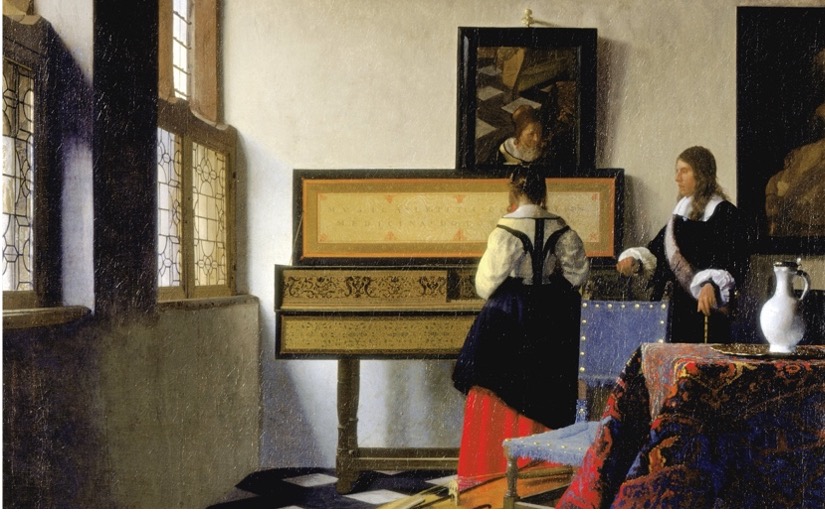

George Deem

As a classical musician, I still find that I’m left with a lot of baggage from the field: more than a decade of internalizing a rhetoric of cultural supremacy that has valorized meritocratic colorblindness; an elitist and parochial donor culture; and a patronizing, subsumptive approach to EDI (equity, diversity, and inclusion), not to mention fundamental issues of accessibility and representation in repertoire canons, teaching methods, and university curricula. Classical musicians and institutions love to throw around the phrase “music is a universal language,” not realizing that embracing transcendence prevents us from listening honestly to the multiplicity of embodied histories, cultures, worldviews, and dreams woven into sounds made and music played.

Even now as I think back on that meeting, I’m not sure I can do much to change my colleague’s mind. For now, what I can do is lead by example; after all, the power of “knowing better” comes with the responsibility of “knowing better than to.” So, I leave with this final meditation: teaching, whether in a group or individually, comprises acts of empathy. A pedagogical relationship is haptic and affective: in instrumental teaching, we physically touch and are figuratively touched by the emotional experiences that create musical expression. Teaching cannot be just the passing of knowledge from master to pupil or the continuation of pedagogical and musical legacies. Rather, pedagogies demand compassionate and vulnerable exploration; we teach our students not in order to demonstrate what we know, but to reveal the extent of what we do not know and to make sense of our knowledge through theirs. When teaching is the process of people reaching out and acknowledging each other, we bring our fragmented selves together to create an expansive picture of a world that is more powerful, more just, and more beautiful than anything we could conjure alone.