In celebration of the end of the school year, we joyfully share The Collective’s first “mini-issue”! In just five jam-packed articles, this small-but-mighty offering grapples with the translation of performance into agency, both via individuals and institutions: how institutional performance either gives agency to individuals or takes it away; how collaborative and competitive agency are enacted in the realms of performance and politics; how individual performance can itself be an assertion of agency against societal and institutional constructs; and how individual agency allows us to build and rebuild institutions to further increase agency for ourselves and others.

Along these lines, the artistic works recommended in this Corner consider the inherently agential nature of performance and the inner worlds of characters whose agencies have been breached by forces outside their control or provoked to unhealthy behaviors by a lack of empathy from either society or the individuals around them.

READ

Vikram Seth — An Equal Music (1999)

In Vikram Seth’s novel, classical violinist Michael Holme performs as part of a successful string quartet, the Maggiore. A former lover, pianist Julia McNicholl, appears at one of his concerts, a decade after they have last seen each other and performed together. Julia is now married and slowly going deaf. The two musicians navigate what remains of their relationship and the impending loss of her artistic identity.

Interestingly, though he has many musician friends, Seth himself has not performed music at any professional level, only taking rudimentary lessons in Indian flute and tabla. Regardless, for me, the best aspect of this book is its beautiful prose describing the power of music and the incredible, unique nature of musical collaboration. Before this novel, I had never read passages that so accurately and stunningly rendered my feelings for music and its performance.

As a sample, one of my favorite excerpts:

How good it is to play this quintet, to play it, not to work at it — to play for our own joy, with no need to convey anything to anyone outside our ring of recreation, with no expectation of a future stage, of the too-immediate sop of applause. The quintet exists without us yet cannot exist without us. It sings to us, we sing into it, and somehow, through these little black and white insects clustering along five thin lines, the man who deafly transfigured what he so many years earlier had hearingly composed speaks into us across land and water and ten generations, and fills us here with sadness, here with amazed delight.

Vikram Seth (p. 79)

For many of us, music is more than our careers; it is the language through which we define our lives, thinking, and relationships. Seth’s brilliant linking of Julia’s deafness and the wreckage of love and longing makes the novel well worth experiencing. The descriptions of musical performance are so luxurious you can almost feel your own instrument beneath your fingers, your musical partners breathing in tandem beside you, and the radiant emanating sounds that blossom and echo in the room.

WATCH

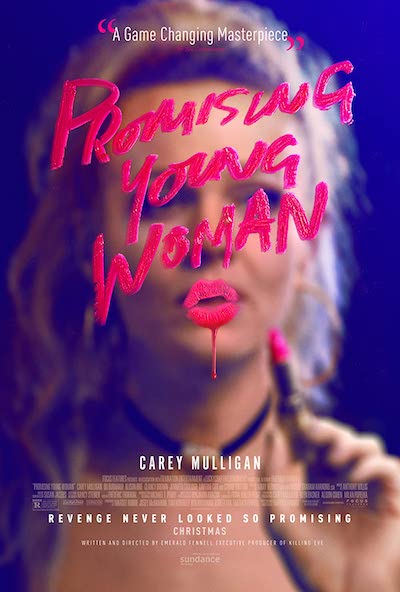

Emerald Fennell — Promising Young Woman (2020)

Trigger Warning: sexual assault/violence

Browsing the Austrian Airlines movie selection earlier this month on my flight to Sofia, Bulgaria, I did not expect a particularly critical or transformative experience (really my goal was to distract myself from the total weirdness of being on a plane after two years of / during an ongoing pandemic). So, stumbling on Promising Young Woman (2020) proved two things: 1. international airlines have stepped up their streaming game, and 2. there’s no time like the present to watch this genre-bending, eye-widening, truly disturbing, and totally spot-on #MeToo-era rape-revenge film. Though it was released nearly two years ago, Promising Young Woman remains urgent, considering the asinine discussions around a woman’s bodily autonomy and impending dismantling of their reproductive rights throughout much of the U.S.

Written, co-produced, and directed by Emerald Fennell and starring Carey Mulligan, Promising Young Woman tells the story of med school dropout, Cassie (Mulligan), haunted by the rape and subsequent death of her best friend, Nina. The film follows Cassie as she targets those responsible both for the event itself and for refusing to seek justice in its aftermath. Besides its timely and unfortunately still timeless messaging, Promising Young Woman is brilliantly written, produced, and acted. Against a chromatic backdrop of neons and pastels, jarringly juxtaposed with the film’s harrowing subject, Cassie is a complex and gripping female lead, seeking vengeance not for herself or her friend alone but on a societal level, and asserting a wide spectrum of femininities and female experiences in the process. Its defiant comedic twists and eerie display of normative rhetoric are genuinely confusing and unsettling, making it impossible for viewers to predict the plot (rare, honestly) and forcing them to sit in the discomfort of recognizing not just the absolute savagery that is rape itself but the savagery of individual, social, and cultural complicity.

The film eschews simplistic representations of how sexual violence brutalizes human life as much as it eschews resolution, opting instead to preserve the very real dissonance and sickening pervasiveness of rape culture in our society, and the structural role of gaslighting in its perpetuation. With this, Promising Young Woman has the power to cut through the noise of uncritical, stubbornly unempathetic (read: largely male, grossly governmental), and effectively violent viewpoints on gender, sex, and agency.

I’ll stop here, to avoid risking spoilers (truly, the story’s appalling twists and turns are worth experiencing with a clean slate), but I will say: while I’m grateful to Austrian Airlines for the experience, I do not recommend watching this film on a plane. The temptation to scream into the void is far too strong.

LISTEN

Music by Bryce & Aaron Dessner, Lyrics by Matt Berninger & Carin Besser — Cyrano (2021)

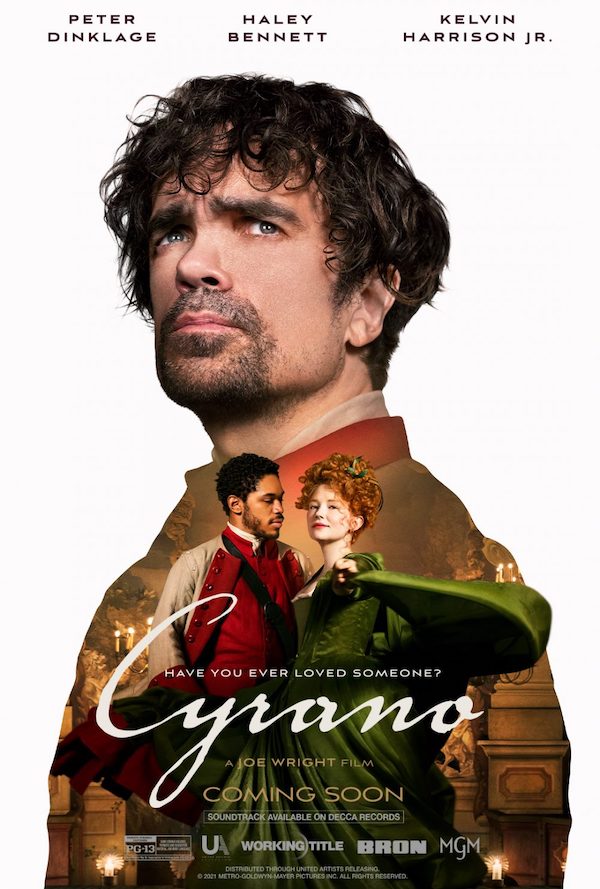

Cyrano (2021), the film directed by Joe Wright, adapts Erica Schmidt’s 2018 musical stage production, which is based on the original 1897 Cyrano de Bergerac play by Edmond Rostand. Whew. Still following? Though you may have heard that this soundtrack is forgettable, I hope you give the movie and the music equal attention to fully appreciate its beauty.

Peter Dinklage plays the archetypal desperately-in-love-with-his-best-friend-but-unable-to-tell-her title role. He is afraid that Roxanne (Haley Bennett) won’t love him back due to his appearance (traditionally, and somewhat ridiculously, Cyrano just has a huge nose; the reimagining of the role with Dinklage, an actor who has dwarfism, is a brilliant choice). Just as he works up the courage to finally profess his love, Roxanne confides in him that she’s fallen for Christian (Kelvin Harrison, Jr.), a fellow soldier in Cyrano’s ranks. To make matters worse, Christian entreats Cyrano to pen love letters to Roxanne on his behalf — after all, Cyrano is ingenious with words while Christian is . . less so.

The music is written by members of the rock band The National; twin brothers Aaron and Bryce Dessner (who is also a collaborative partner with the San Francisco Symphony) composed the music, and Matt Berninger and his wife Carin Besser wrote the lyrics. Though few seem to find fault with the narrative and performances as a whole, I was surprised to see many critics blasting the music for being trite and simplistic. Mark Goodwin said the music “languishes” and Mick LaSalle said that anytime “anyone starts singing it’s time to get up and go to the bathroom.” It makes one wonder if LaSalle just didn’t like the transformation of Rostand’s play into a musical, or if he likes musicals that much at all. While I must say that it took me a moment to reconcile the anachronistic music with the period piece, once I leaned in, it worked extremely well; for me, the lyrical melodies and lush orchestration perfectly epitomize the Broadway-musical-meets-contemporary-rock-music genre.

With a continual underlying rhythmic propulsion that inevitably impels the story forward, I find it absurd to call the music “languid.” Additionally, the cast may not all be trained vocalists, but their emotional work really makes the performances sing (haha). The music ensures that the story remains focused on the blind emotionality of these characters: Cyrano’s pride, Christian’s naïve passion, and Roxanne’s desire to be swept away in love. Their inabilities to see the others’ hearts past their own emotions compel the music to be dreamlike and fantastical.

Berninger and Besser’s empathic lyrics climax into nuance and complexity during the exquisite “Wherever I Fall,” sung by three soldiers preparing to enter battle (performed by Glen Hansard, Sam Amidon, Scott Folan). It wasn’t until a careful third listening that I completely comprehended the song’s clever and heart-wrenching full meaning. The progressive stories told by each soldier metaphorically peel back the layers of Cyrano’s inner psychology, from a man who has seemed to live a full life, to a man who has never known love, to a man who damned himself to hell by leaping into action without enough forethought. Also deserving of a shout-out is “What I Deserve,” deliciously performed by the villain De Guiche (Ben Mendelsohn), bent on getting Roxanne for himself. The song highlights Mendelsohn’s range, and his articulation and color choices snarl out a hyper-realistic and over-privileged threat, not meant to be pleasant-sounding, but as fully committed to character as Jeremy Irons in The Lion King.

Soaring and recurring melodies and themes, tender instrumentation, and courageously heart-felt performances by gifted actors drench this classic story with a hyper-reality that fulfills a musical’s highest promise: the immersion of the audience into the peak emotional notes of its characters. The soundtrack for Cyrano may be just as initially unexpected as the casting of Peter Dinklage in the title role, but upon a true engagement with the material and the performances, they are found to be equally genius.

As a mosaic community that seeks to celebrate and invigorate the agency of individual artists, we prize this chance to contemplate agency through performance, a discussion we intend to expand upon in the future. Until then, we leave you with a poem called “Self” by James Oppenheim (1882-1932), serendipitously “poem of the day” on poets.org on May 24 two years ago, that speaks to the intentional recognition of oneself as part of a living, breathing system.

Once I freed myself of my duties to tasks and people and went down to the cleansing sea... The air was like wine to my spirit, The sky bathed my eyes with infinity, The sun followed me, casting golden snares on the tide, And the ocean—masses of molten surfaces, faintly gray-blue—sang to my heart... Then I found myself, all here in the body and brain, and all there on the shore: Content to be myself: free, and strong, and enlarged: Then I knew the depths of myself were the depths of space. And all living beings were of those depths (my brothers and sisters) And that by going inward and away from duties, cities, street-cars and greetings, I was dipping behind all surfaces, piercing cities and people, And entering in and possessing them, more than a brother, The surge of all life in them and in me... So I swore I would be myself (there by the ocean) And I swore I would cease to neglect myself, but would take myself as my mate, Solemn marriage and deep: midnights of thought to be: Long mornings of sacred communion, and twilights of talk, Myself and I, long parted, clasping and married till death. — "Self" by James Oppenheim

When we see ourselves as Oppenheim suggests — when we decide that we are “free and strong,” that we and all living beings have these depths — we can begin to collaborate and grow. May the articles in this issue and recommendations in this Corner inspire you to reflect on your own agency, on how you can employ the full extent of your power, as you exist alongside others, rising up within and transcending the bounds of social constructs and establishments.

Articles in this issue:

- Featured Article: Performing Create more joy: An interview with Shubhangi Sakhalkar by Editors

- Diversity DEI initiatives in American orchestral organizations by Jett Walker

- Ethics Does your institution deserve respect? by Vijay M. Rajan

- Politics Agency is a nonscarce good by Vijay M. Rajan

- Nugget May 2022: Performer-audience symbiosis, or “Go away kid, ya bother me” by Ryan Gould

To clarify; I adore musical theatre. I consume an awful lot of it. I personally find the Cyrano soundtrack lacks forward propulsion and slows down the plot instead of enhancing it. I don’t think that’s helped by the vocal performances – but we’re all different and I’m pleased that you enjoy it.

Thank you for clarifying! Happy to have your thoughts, and I certainly enjoyed reading your review! What’s your favorite musical?

Upon rereading my writing, I felt like I was little unfair to you, lumping your review in with many others I’d read. I’ve updated, and specified my comments above. Thanks so much for commenting!