In this third and final part of this series, I conclude a conversation about decoding contemporary American politics through storytelling techniques employed in Hollywood. In part 1, I spoke about how politicians have increasingly relied on unresolved endings; in part 2, I spoke about how institutions employ performative risk; and in this final part, I will delve into how megacorporations have co-opted a core idea that beats at the heart of all storytelling: agency.

It is my contention that the people of this country are continually being conditioned by popular capitalistic narrative conceits within major Hollywood studio product and politainment to believe some crucial falsehoods about the nature of the world — and that these misconceptions and deceptions have led to our divisive and ignominious present.

Scarcity

In Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019), space alien Thanos (Josh Brolin) defines the central problem of our universe: overpopulation. He claims that since there are too few resources to satisfy the needs of all creatures, he must randomly erase from existence half of all living things throughout the universe.

When these movies were released, I found it interesting that many audiences responded by claiming Thanos to be a sympathetic villain; they argued that while his thesis was empathetically stunted, it was still logically sound. His goal supposedly represented utilitiarianism at its most brutally truthful, and that his conclusion was based on an irrefutable truth.

Was it?

The fundamental economic theories of modern-day American capitalism are built upon the sacrosanct assumption that the rarer (or scarcer) a good in demand, the higher should be its value. The hypothesis of scarcity, and its subsequent applications, can be traced back to the fathers of economics: Malthus, Robbins, Samuelson. This argument is sensible. If a popular individual furniture-maker can build only ten pieces a year, and a hundred consumers each want one, then the price will increase until only ten are willing to pay what it takes to own one of the pieces. Our entire system of worth was therefore predicated on the scarcity of a commodity’s scarcity — as long as there was a demand for it.

The problem arises when a product that is not scarce is redefined as such, in order to artificially inflate value. Take deBeers and the diamond trade. It is increasingly well-known that the company has hoarded jaw-dropping quantities of the gemstone to perpetuate the public perception of scarcity — and therefore high-value.

This example illustrates that financial value is no longer dependent upon scarcity, but upon what the public believes is scarce. Megacorporations now have a very attractive financial motive to reshape the narrative to inflate the value of their commodities.

If people can be gaslit into believing in the scarcity of a particular good, then its value skyrockets. For major corporations, the financial incentive is not to find truly scarce goods (a difficult task in an unreliable and hypercompetitive marketplace) but rather to: 1) redefine plentiful goods as scarce; 2) redefine nonscarce or “free goods” — which have no opportunity cost — as scarce; and 3) perpetuate the myth that scarcity necessitates an increase in demand and therefore an increase in value.

To achieve these goals, fashion company Burberry burned thirty-eight million dollars of its own inventory to maintain exclusivity. “Reputed” auction house Sotheby’s works to ensure that NFTs — a laughable concept that would have once been clearly defined as a nonscarce good — are seen as scarcer than their identical digital copies. Megacorporations no longer need to prove demand, but rather seek to presume it. The lie of scarcity creates a myth of demand that then provokes demand in the susceptible marketplace that then accords value to a good of little or no worth. Our gross domestic product is increasingly built on falsehood, the repeated gaslighting of the impressionable consumer, and goods of questionable value.

And that brings me back to Thanos.

Are the natural resources in our universe too few for all life because of previously unprecedented human population levels? Or are we suffering from an egregious misallocation and hoarding of resources? If it’s not too rude to suggest that half of all life can vanish without a trace to solve current societal issues, is it too rude to suggest that Thanos just snap his fingers and vanish half of the wealthiest individuals and corporations instead?

Is there too little food supply to end world hunger or too little food efficiency infrastructure to avoid food waste? It is my contention that megacorporations would rather waste resources than distribute them efficiently and equitably. The true problem is not scarcity, but old-fashioned American corporate greed.

Through his thesis, Thanos can quickly be revealed to be just another moronic half-wit who believes the best way to save resources is to eliminate huge swaths of people who aren’t even getting access to them in the first place.

But megacorporation Marvel, now owned by more-megacorporation Disney, does not spend any of the nearly six hours of combined run-time of these two films making a logical argument against its own villain, no matter how brief, despite the fact it does spend the time to help him make his arguments. The reason we are given for the heroes fighting back is that his sophomoric thesis is sad, not intellectually flawed. Tony Stark solves time travel in three minutes but has no time left over for cutting quips about how getting rid of half of our population of bees would bring about ecosystems collapse.

I know — it’s a superhero movie, not a philosophical treatise, but Hollywood has long gone out of its way to ensure that plot elements that are nonscarce are instead treated as if they are scarce, because ultimately, Hollywood is a conglomeration not of artists but of corporations that happen to hire artists. It is in these corporations’ best interest to continue to perpetuate the myths that feed into our current economic systems, not to challenge them.

And if there is one nonscarce narrative good that is hoarded more intensely than any other by Hollywood decision-makers in their products, it is the narrative device of character agency.

Agency

While many propose that screen time is the most accurate metric by which to measure character impact, this is patently untrue. Anthony Hopkins appears in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) for only sixteen minutes, but walked away with an Academy Award and a reputation for playing the most memorable role in the film. Furthermore, movies which feature a male and female co-lead with equal screen-times (La La Land, Marriage Story, A Star is Born, Edge of Tomorrow) or even a primary female lead (My Best Friend’s Wedding, Arrival) consistently fail the Bechdel test, but luckily, dimensionality is not usually an indication of a character’s staying power within an audience’s mind either. After all, is Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men (2007) three-dimensional, or is he memorable because he is so terrifyingly one-dimensional?

If neither screen-time nor dimensionality are the most impactful character currency, then how is a character built to last in an audience’s memory?

The answer is agency, defined as the extent to which a character’s choices impact and shape the larger narrative.

Sandra Bullock has a considerable amount of screen-time in Speed (1994), but ultimately, almost all the choices that shape the story belong to Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves) and Howard Payne (Dennis Hopper). Largely, Bullock’s Annie (who isn’t even given a last name) is just along for the ride, reacting to Payne’s nefarious plans, the tragedies happening around her, and Traven’s heroics. Despite being the love interest and an integral cog in every action scene, her character is not meant to be remembered in the same iconic way as the men’s.

The film 12 Years a Slave (2013), based on a true story, provides another example. In the 1840s, Solomon Northup, a black Northern freeman, is kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana. For twelve years, he is sold from master to master, unable to actually impact his own narrative. For the majority of the film’s two-hour and fourteen-minute run time, we watch him and the other enslaved weeping and broken by all the evils of this era. Though he becomes close to the enslaved Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o), he is forced to stand idly by — or even participate — as she is brutalized.

Finally, in the last act, Solomon meets a Canadian abolitionist named Bass (Brad Pitt), who appears in the film for fewer than ten minutes. Bass helps Solomon prove his “freeman” status and get home to his family up North. A final shot in the South depicts Northup balefully leaving Patsey to her sad fate at the plantation. When the movie cuts to black, we are informed in end text cards:

I sat in the audience as the credits rolled, jaw open, attempting to comprehend the strangeness of what I had just witnessed. This movie, which was a hit with critics and audiences alike, had just happily given most of its agency to the white slave-owners and the white abolitionist who had little more than a cameo. It had also relegated all of Northup’s own amazing agency-filled true story to text cards.

According to the tenets of narrative agency, these choices led to the likelihood that what people would most remember from this antebellum story led by black actors, directed by a black man, and about a historical black man is — drumroll, please — Brad Pitt.

Also, the tropes of Manic Pixie Dream Girl (Elizabethtown, Garden State), Magical Negro (The Legend of Bagger Vance, Driving Miss Daisy), and Disposable Woman (Braveheart, Gladiator) are problematic because these female and/or minority characters exist only to increase the white male protagonist’s own agency; their experiences and goals matter only in terms of how well they support the “awakening” of the white male protagonist into his own power. The only agency minority characters are frequently allowed to have is the ignition of white male efficacy.

The Academy-Award-nominated film The Blind Side (2009), for example, is considered racist by so many BIPOC audience members because all of the agency in this story about Michael Oher succeeding in becoming an NFL player is attributed to his adoptive white parents. Oher, played by Quinton Aaron, is largely depicted as a lost, obedient puppet, while Sandra Bullock’s Leigh Anne Tuohy makes nearly all the choices that impact his life. Though this movie was based on a true story, even the real Michael Oher opined that he wished the movie had discussed how much work he himself did to learn football; he is quoted as saying, “I’ve been studying, really studying, the game since I was a little kid.” In the movie, however, his character barely understands football and has to be taught the game by Leigh Anne and her son SJ through the use of kitchen condiments.

Hilariously, the movie even ends with Leigh Anne questioning whether she has taken too much agency away from Oher in regard to his choice of college, but then concludes with a definitive and happy “no,” since the character of Michael is just grateful to feel included at all. These choices, made by writer and director John Lee Hancock, do not lead to problems of screen time or character dimensionality; they instead again rob the minority character of the crucial resource of agency.

Compare this with Short Round (Ke Huy Quan) from the second Indiana Jones movie, who is still largely remembered fondly by the Asian community, despite the accent that serves as the basis of most of his humor. Short Round is memorable because he escapes from captivity, reawakens a brainwashed Indiana Jones, and saves the whole day. (The film’s female lead, on the other hand, comes up laughably short when it comes to agency.) Short Round is a hero, and not just of some other talked-about adventures or by reputation, but in the on-screen plot of the very film in which he appears! How novel!

Hollywood has long understood that screen-time matters less than actual impact over the larger plot. Studios have long been generous with screen time to women and minorities, but far stingier with their impact over the larger narrative. Agency is the high-value resource that Hollywood has claimed to be most regrettably “scarce.” Studios treat this actually nonscarce good as if it were as tangibly limited as screen-time; in film after film, they behave as if agency must be taken from minor characters to more effectively tell the protagonist’s story. Efficacy is redistributed from the many and granted to the “rightful” few.

The absurd narrative conceit that agency is a scarce good that cannot be spread liberally between major and minor characters for fear of diluting the story is called competitive agency. And it is patently, and ridiculously, false.

Just take Mission: Impossible II (2000).

How Ethan Hunt didn’t save the day

Mission: Impossible II is the only film in the blockbuster series not directed by a white man. Star and producer Tom Cruise sought out John Woo because he felt that the Asian director would be able to helm stunts of the kind typically not allowed or seen in Hollywood. Interestingly enough, it is also the only film in the series in which the white male protagonist — the iconic daredevil superspy Ethan Hunt — is not the one who ultimately saves the world.

In this film, Ethan Hunt is tasked with finding the dangerous biological weapon, Chimera, a virus that kills anyone it infects after an incubation period of twenty hours, and Bellerophon, its antidote. If the terrorist villain Sean Ambrose (Dougray Scott) manages to release the Chimera into the world, a deadly global pandemic will result, allowing Ambrose to sell Bellerophon to desperate governments at an exorbitant price. Ethan must send his love interest, Nyah Nordoff-Hall (Thandiwe Newton) back to Ambrose, her ex, to spy for the Impossible Mission Force.

At the film’s midpoint, only one vial of Chimera remains, placed in an injector gun. Nyah holds the virus, but Ambrose has her at gunpoint. Ethan is watching but can’t do anything; Nyah will be shot if he even moves. Ambrose demands that Nyah hand over the last vial of Chimera.

When I first watched this movie as a college student, I remember thinking, What stunt will Ethan Hunt do to get out of this one?

And instead, the music swells dramatically, and Nyah injects the Chimera into her own arm.

Ethan is shocked. Ambrose is shocked. I was shocked. Since Nyah is willing to die before the virus can spread to others, there is very little risk of the world being infected by Chimera. Ethan’s goal is now not to save the world, but to find the antidote within twenty hours to save Nyah. A BIPOC non-spy female love interest character just saved the world in a Mission: Impossible movie.

It was a brilliant inversion of agency, a sparkling moment in what was perceived to be an otherwise lackluster film.

But apparently, it was too much for Hollywood. All the excitement I felt deflated immediately when the following happened.

Ethan grabs Nyah and demands, “What do you think you were doing?!”

Nyah responds, “I wasn’t thinking. Just trying to stop you from getting hurt, that’s all.”

What?! I could not believe it. Giving this character this agency was seen as such a risk that it had to be mitigated by the character herself admitting that she hadn’t made a conscious choice. Since the very definition of agency has to do with choice, suddenly, this heroic act was… an unthinking impulse? In this revisionist telling, Nyah had injected herself not to save lives, but to support the white male protagonist? For those aware of narrative tropes, she stuffed herself into a fridge!

What benefit was perceived by these maddening lines of dialogue?

Agency was being treated as scarce so that no importance could be taken away from the iconic Ethan Hunt and given to his meager love interest. Nyah’s response that she “wasn’t thinking” does not actually affect Ethan’s behavior, the plot, or ensuing events; yet these words are included to preserve the false concept of competitive agency.

To showcase an inverse example, in which agency is thankfully not treated as competitive or scarce, the relatively minor character of Walder Frey (David Bradley) in Game of Thrones (2011-2019) makes one of the most iconic and unforgettable choices in the entire series. This character, feeling snubbed by Robb Stark (Richard Madden) for not following through on his promise to marry Frey’s daughter, executes the infamous Red Wedding in which he murders several protagonist characters within the Stark family. The scene works so well because audiences have been conditioned to believe that minor characters cannot exhibit that kind of agency; it makes it deeply shocking.

When all characters, regardless of how minor, are given agency, it lends authenticity, truth, and deeper conflict to narrative. It also provokes the remaining main characters to make more decisions in response: in effect, to display more agency.

Breaking Bad (2008-2013) is another TV series that understands this. Even relatively minor characters constantly make decisions of their own accord, in line with their own goals, and these decisions necessitate that Walter White (Bryan Cranston) becomes more tactical in how he uses the assets at his disposal to respond to each challenge, solve each problem, and vanquish each foe. The agency of these other characters is what puts Walter White’s back against the wall — and cements his resourcefulness, intellect, and ruthlessness within our minds as evidence of the iconic and unforgettable nature of his character.

The essence of complex world-building is ensuring that a large roster of characters all have individual goals, and act in accordance to affect the larger narrative. Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) in the classic film The Godfather (1972) does not want to follow in his father’s Mafia footsteps. Several acts of agency are committed by minor characters to result in Michael ultimately becoming the new head of the Corleone crime family. Michael’s brother-in-law Carlo (Gianni Russo), for example, is abusive to his sister Connie (Talia Shire), compelling Michael’s older brother Sonny (James Caan) to come out of hiding and speed to his sister’s defense. Consequently, Sonny is gunned down by a warring mob family. In this way, the relatively minor character of Carlo makes a choice which propels the larger narrative in an artful and intricate manner.

Without a large roster of characters acting with a belief in their own agency, a world feels unnaturally small, like a certain film series that takes place a long time ago in a galaxy far far away, where it seems as if a character can only make a difference if their last name is Skywalker, Palpatine, or Solo.

In good storytelling, agency must be a nonscarce good. The old cliche of “a rising tide lifts all boats” is clearly applicable here. Yet, again and again, Hollywood has treated this commodity as a scarce good, to be given ideally only to the protagonist, and if being very generous, perhaps to the primary villain as well.

No wonder this pervasive narrative conceit has so permeated our culture and politics.

A horribly skewed marketplace of ideas

Modern America is no longer traditionally capitalistic; it is instead an oligarchy of megacorporations that, since the landmark 2010 Supreme Court Citizens United case, are granted the rights of individual citizens. This opened the door to individuals competing for agency with megacorporations, especially in terms of our elections.

This naturally results in a situation where politics in this country are increasingly controlled by a few with agency — “chosen” people who are meant to be championed for or lobbied against. This is a definition of “democracy” that I believe benefits the Democratic and Republican parties in equal measure. It takes us away from a free and fair marketplace of individual ideas and instead makes it about red v. blue, Biden v. Trump, or Soros v. Murdoch.

When the American people are gaslit into believing that the proper narrative is one in which “minor” characters can only affect change in the larger narrative by affecting the true lead, large monolithic corporations and those already in power always win. We spend so much time and energy talking about whether Bill Gates or Elon Musk will save the world, instead of the actual truth, which is that some poor underpaid schmuck scientist somewhere, who actually has the intelligence to solve climate change, just watched her company go under because of the predatory capitalism of underqualified and overglorified hoarder billionaires. But megacorporations do not want us to think of this as a tragedy; they demand instead that we perceive it to be the natural state of things, necessitated by the scarcity of agency.

What are these megabillionaires actually amassing with their ridiculous purchasing power? It’s not comfort or luxury or convenience or fame. No, they have more than enough of all of that. So what is left to purchase?

Even more agency.

Elon Musk wants to buy Twitter because he desires more control of a social media platform that has a recent proven history of being unfathomably important in presidential politics.

Jeff Bezos is a coward who fears a free and fair marketplace of ideas, choosing instead to prey upon, steal from, and destroy any potential competition — because he knows his ideas are actually not the best and so would not succeed in any capitalistically equal marketplace.

These two men want their choices — and increasingly their choices alone — to impact the larger narrative.

Agency is what they’re buying. And corporations across the board want to perpetuate a culture based on three essential falsehoods: 1) agency is so scarce a good that it cannot be indiscriminately disseminated; 2) agency can therefore only be naturally enjoyed by the “chosen” main characters; and 3) they are the main characters because they are the most deserving; because of their skills, intellect, or folksy common sense, they have the best ideas for success in the free market. That is how our modern political system operates, redistributing the potential for impact from the many to the few — under the guise that this prevailing trifecta of lies is logical, natural, and fair.

These three falsehoods are mirrored in so much of cinema. The ultimate hero of Amistad (1997) is not Cinque, the enslaved African who led a bloody revolt upon the titular ship, but former President John Quincy Adams. Men In Black: International (2019) was much-lauded for including a “woman in black”; regardless, the film continues to reserve character agency for the men. The story of real-life African-American gay pianist Don Shirley is told in The Green Book (2018) through the eyes of his somewhat racist white chauffeur — and it is Shirley who has to learn the ultimate lesson about being more open.

So many of these films, though supposedly championing minorities, are written — with beginnings and endings chosen for exactly this purpose — to perpetuate the myth that only the hegemony can ultimately affect or deny change. No wonder so many Americans, including myself, feel so disenfranchised and marginalized. We have been cast not in lead roles, nor as supporting actors, nor even as day players; we are meant to be extras, satisfied with not leaving a larger impact and useful in the larger picture only as atmosphere.

Power, we are told, is for the few, and the individual’s only option is to be entertained and pledge allegiance.

Can value come from plenty?

The first rule of improv performance is “Yes, and.” A performer must accept their scene partner’s choice as truth, then respond by building from that foundation. Rejecting or limiting the other’s suggestion is simply not allowed. Competitive agency, as a concept, flies in the face of this philosophy. If even improv is made better and more intelligent through inclusivity, why are we treating our country as if our agency is lessened by another’s access to contribution?

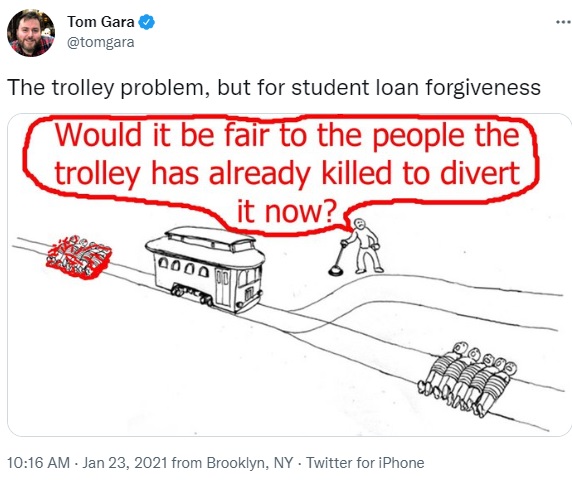

The reason so many Americans give for being against student loan forgiveness is that they have already struggled to pay off their own. Giving aid to those with debt is somehow seen as taking resources away from those who no longer have debt. The American people are in competition with each other for agency, all the while gaslit into a system that allows the “chosen” to hoard it without condemnation.

Economic theory states that scarce goods in demand are valuable. But worth can also come from that which is plentiful, just not plentiful enough. That too is a scarce commodity in demand. An animal is not only valuable within its ecosystem if it’s endangered, after all.

Similarly, if teachers were desperately scarce, so that there were only one teacher for four-hundred students in a classroom, would the available teachers themselves become more valuable? Is this not a situation in which as salaries would rise to accommodate the increasing demands of the job brought on by the scarcity of labor, the precise nature of those demands would actually diminish the quality and value of even the finest educators?

Some of our resources become the most valuable precisely when they are nonscarce, like the air we breathe, the water we drink, or even the Internet we use.

Artists, thinkers, and teachers exemplify three categories of labor that have more value in their plentitude than in their scarcity. Businesses are more valuable when plentiful than scarce (a dangerous thought in an economy that trends toward continuous monopolistic conglomeration). We must do what we can to find economic value in that which is bolstered by plenty, not profit.

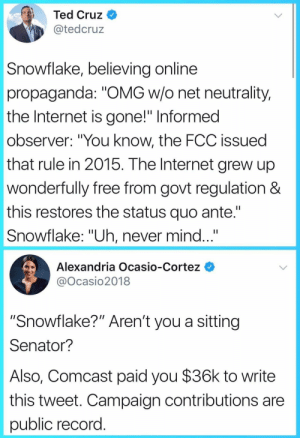

The Internet is an excellent example of a “free good”; it provides rewards to the entire world when available freely to all populations. It cannot be privatized, bequeathing control of this invaluable resource to a few megacorporations. Net neutrality helps maintain public agency.

The same is true for universal health care. Privatized health models fail to efficiently distribute resources because their goal is not human resource growth but revenue generation. It’s not just a moral peril; it’s intellectually illogical and disturbingly stupid. The dirty rotten American secret is that welfare for the poorest among us is actually perfectly utilitarian.

Yes, our global population is at nearly eight billion. Yes, that is a heretofore unseen encumbrance on existing resources. But that population itself is also a resource. The global population was 2.7 billion when the brilliant Jonas Salk produced the smallpox vaccine in 1954. If we focused on ensuring that our entire current population had the advantages of education, access, and impact, we would be three times more likely than 1954 to find the minds necessary to solve the great challenges of our time. So why is population seen as a drain on resources instead of a huge vein of raw gold yet to be fully mined? We must demand a system in which agency is available to all, and the marketplace of ideas is truly free and fair. It seems increasingly like a pipe dream, but equity is not just a moral good; it is our best possible chance to actually solve the complicated problems that plague us today.

Conclusion

It is impossible to speak about modern American politics without addressing megacorporations and their impact. When Google brands its complement of products as an ecosystem instead of a showroom, it gaslights the American people into thinking of its artificially created and very unnatural infrastructure as somehow ecologically balanced and maximally resource-efficient. When Elon Musk is asked to host SNL, despite not being a performer to any degree, he merely further establishes himself as the “main character” to whom we must or must not throw our support. But the question is not whether Google or Elon Musk deserve the power they have, but why so many others feel as if they can leave no impact at all.

In America, we must awaken from the underlying myths that poison our thinking and handicap our potential. A consistent machine operates in our entertainment and politainment, reinforced by narrative techniques that can be studied and decoded. The American people can only break free from gaslighting when we become aware of the specific techniques employed by politicians, institutions, and megacorporations as part of this relentless propaganda.

In these past three articles, I have used the Hollywood studio narrative concepts of unresolved endings, performative risk, and competitive agency as lenses through which to understand larger American thinking. I wished to write this series because this terminology is not frequently used outside of writer’s rooms, and is rarely applied in terms of impact on the political stage. But, as stated in my first article, cinema is a grand weapon that works on conscious and subconscious levels, providing the structure through which we perceive our world.

Even if the spread of these concepts in entertainment is not always deliberate, audiences must become aware that since there is a financial fall-out to almost every decision made in media megacorporation boardrooms, none are made flippantly.

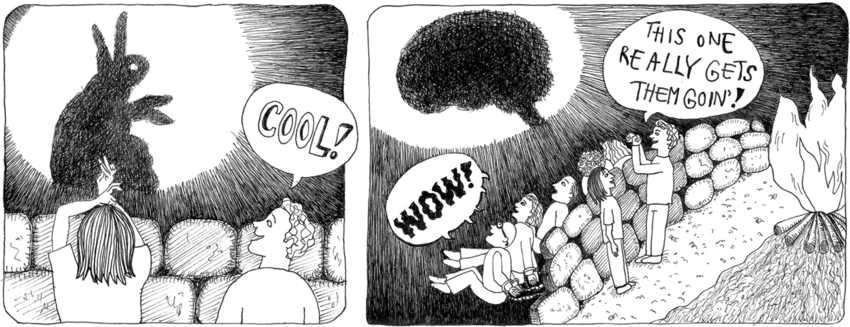

In response, we must have the language to parse whether contemporary media shows truth or fiction. A comprehension of media theory is the only possible hope that we all have to awaken from the shadows on the wall of our time. Ironically, projected cinema is literally a shadow on the wall.

Perhaps this article series appealed to me because I increasingly feel as an American the way I feel as an audience member in a movie theater — as if I had no way to take part in the creation of the thing before me, no ability to impact the story, no avenue to do anything but like or dislike, support or oppose. I am completely fine playing audience to someone else’s creative work, but I refuse to sit passively before the political fate of our country and world. The tools of story have been weaponized by political lobbies, public relations firms, and news networks on behalf of politicians and corporations to lull me into accepting the false narrative that I am only a consumer from whom a few dollars can be taken when I am trained to like what I see — a false narrative that is then frustratingly, increasingly made true through the power of its normalization.

No, thank you. I’ll take agency, please.

Because if I am ever in the position where, after I have made a choice that leaves an impact upon the world, I am grabbed by the shoulders and asked, “What do you think you were doing?!” the answer I would be most ashamed to give:

…

“I wasn’t thinking.”