In this autoethnographic essay I outline the ways I (a white, cisgender female, assistant professor of ethnomusicology in a department of music) worked to establish an inclusive and equitable space for engaging with music and activism across my department and university by developing and crafting a visiting artist series focused on Music, Race, & Social Justice. I acknowledge that this has not been a perfect process (I often feel overwhelmed and question my own ability to do the work), but I’m committed to making it sustainable and to serving our community. My aim here is to offer a model for how we might work outward from within the structure of university music departments — where, as musicologist Loren Kajikawa notes, we “need not only to become more diverse and inclusive but also to come out into the world and help to create spaces for everyone to play.”[1]

Like so many others, my university grappled with how to address the rise in Black Lives Matter protests spurred by the death of George Floyd in May 2020 — along with the intent and impact that hastily written statements with no follow-up can have. My department, an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Music, offers a Bachelor of Music with concentrations in performance and composition, a Bachelor of Music Education, and a Bachelor of Art with concentrations in music and music theory, with students receiving a liberal arts education. As in many music departments, I am the lone ethnomusicologist — representing the assumed “other” in many ways. My courses fulfill our global diversity and multicultural requirements and I oversee our global music ensembles (mariachi, Balinese gamelan, and Ghanaian drumming and dance). Now entering my fifth year at MSU Denver, much of my teaching has been clouded by my own cancer treatment and the pandemic, but also by the national push to decolonize music curriculum and scholarship (and the challenges we face in doing so). I share all of these things because they have greatly influenced and shaped how I approach my own scholarship, pedagogy, and activism.

MSU Denver, a public university located in downtown Denver, Colorado, was founded in 1965. Today it has one of the most diverse student bodies in Colorado: over half of the school’s undergraduate students are first-generation, and 50.3% of the undergraduate student population are students of color. The main campus has occupied the former Auraria neighborhood, one of Denver’s oldest Hispanic neighborhoods, since 1977, when the community living in Auraria was relocated and displaced by the development of the campus (today a “Displaced Aurarian Scholarship” provides funds for tuition to former Aurarians and their descendants). In 2019, the University was designated a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI). My positionality in my department, coupled with our university-wide commitment to anti-racism and inclusivity, has shaped not only my teaching, but also my own continued education. My personal commitment to student-centered, culturally responsive pedagogy and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives has been shaped before coming here by my own experiences teaching and studying at small liberal arts colleges, music and arts conservatories, and research institutions.

Our own department BLM Statement (published in June 2020) is just that — a statement. Deeply rooted systemic problems do not have simple fixes, nor should they. In developing our own, we sought to acknowledge how we can (and must) do better. Personally, I took a very direct approach, identifying a set of actionable items for myself. I helped to arrange virtual microaggression and implicit bias training for our fulltime faculty with our VP for Diversity and Inclusion, began to evaluate our musicology curriculum for title and content revisions, joined a university working group on Open Educational Resources (OER) as a way to evaluate and increase access to materials for our students, and developed and proposed a new general studies course with no prerequisites — Music, Race, & Power — that builds on theoretical approaches to race, ethnicity, and social identity. But the most visible (and audible) task that I took on was to organize a year-long visiting artist series with the goal of highlighting the voices of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) musicians, performers, and scholars.

Music, Race, & Social Justice Visiting Artist Series

My series was derived from our BLM Statement: “we realize that representation matters.” I wanted to develop a way for our students — but also our larger community — to engage with music in new ways. Knowing that the 2020-2021 school year would likely be at least in-part virtual (spoiler: it was nearly all online), I saw a void to fill in the way of our usual slate of performances and imagined a series that would provide our community with an opportunity to interact with visiting artists through performances and talks accompanied by moderated discussions. My hope was to provide an inclusive space for us to begin the conversations needed to spur change and to begin the work of decentering whiteness and engaging with music and activism in my department. I imagined this series as not only a space for BIPOC performance, but also a way to create a place for difficult conversations about the intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality in music.

With the go-ahead to pursue it (and some repurposed funds from in-person events now made impossible), I began talking with friends and colleagues, formulating lists, and reaching out to possible guests. I also met with our VP for Diversity and Inclusion, Dr. Michael Benitez, to discuss how to broaden the scope of the series. Benitez was immediately supportive and brought his own lens as a scholar whose work focuses on student identity and hip-hop culture. We met several times over the course of the summer as I formulated a list of performances; this process included: sourcing ideas from a wide range of voices; reaching out for discussions with everyone; narrowing in on a variety of artists; and organizing performers, moderators, and technical assistance. The virtual realm presented challenges (notably related to sound quality and internet connections) while proving easier in many ways, as I was only presented with how to bring people together over a livestreaming platform.

During the 2020-21 academic year, I planned, organized, and hosted ten livestream events as part of our inaugural Music, Race, and Social Justice Visiting Artist Series. Like many of us in music departments, I’m usually tasked with organizing and hosting one or two large performance events “in my area” each year, but for this I made a point of reaching beyond my area of expertise and bringing in artists who could connect with our department in different ways. The 2021-22 academic year saw a shift from online to in-person (with a livestream option made available), as well as a reduction in the number of events to allow for an expansion of more sustainable artist residencies.

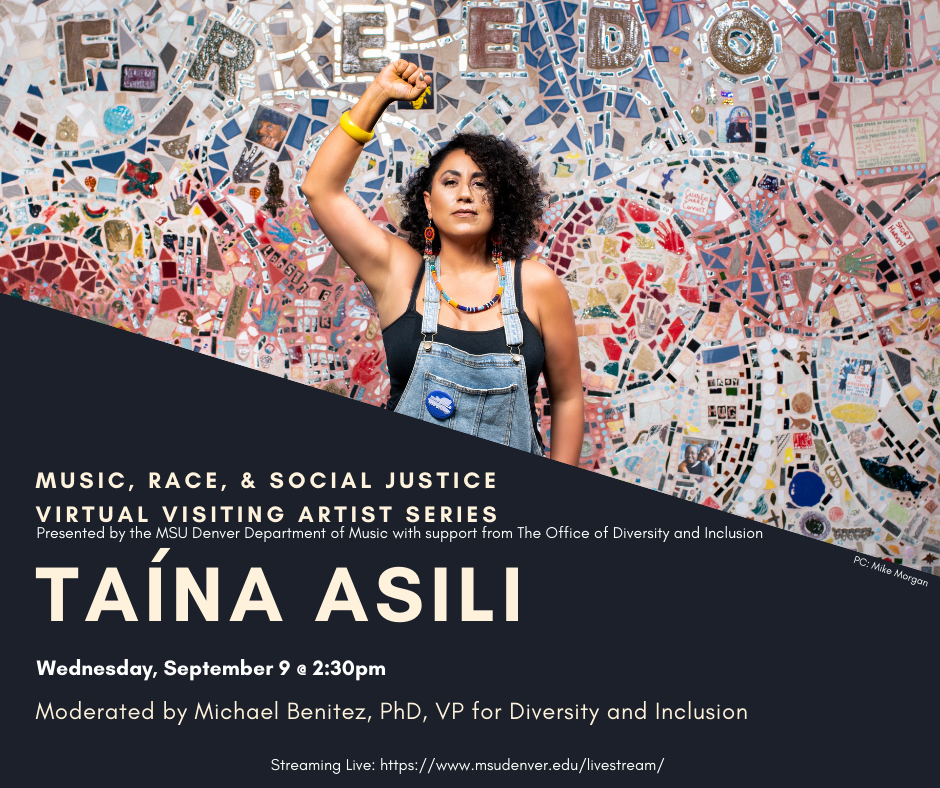

The series opened on September 9, 2020 — marked by the first snow of the year in Denver — with returning artist Taína Asili (with whom I had previously worked at MSU Denver and at a prior institution). Asili is a New York-based Puerto Rican singer, filmmaker, and activist “carrying on the tradition of her ancestors, fusing past and present struggles into one soulful and defiant voice.” She joined us from her living room with her partner Gaetano Vaccaro, a queer filmmaker, educator, and musician, for a pared down acoustic performance accompanied by a moderated discussion with Dr. Benitez. With this first performance, our format was set (with some tweaks over time): I would introduce the series and welcome our moderator and guests, we would share our university land acknowledgement developed by the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, the moderator would introduce our visiting artist, and we would turn it over to the performance followed by the moderated discussion.

Figuring out the livestream itself was an issue of its own, as we bounced between platforms and tried to balance sound from our respective homes. But the events themselves felt meaningful and thrilling — and ended with me sitting at my dining room table. The sense of community engagement that I missed, coupled with growing Zoom fatigue, was something we worked to establish (in small ways) through audience interactions. In one memorable moment, RAPtivist Aisha Fukushima led our attendees in a gratitude reflection and meditation. A friend and student texted me following the event with a simple: “Ommgggh.”

In addition to Taína Asili, the fall 2020 events included:

Members of The Dream Unfinished, an activist orchestra that uses “classical music as a platform to engage audiences in dialogues surrounding social and racial justice,” moderated by our Director of Orchestras, Dr. Brandon Matthews:

Nancy Méndez and ethnomusicologist Dr. Alexandro D. Hernández of “jarocho punk” band ¡Aparato!, who provide a “science fiction soundtrack for tomorrow’s Raza, ‘the people,’ time travelers and visionaries,” moderated by former MSU Denver affiliate faculty member Putu Tangkas Adi Hiranmayena:

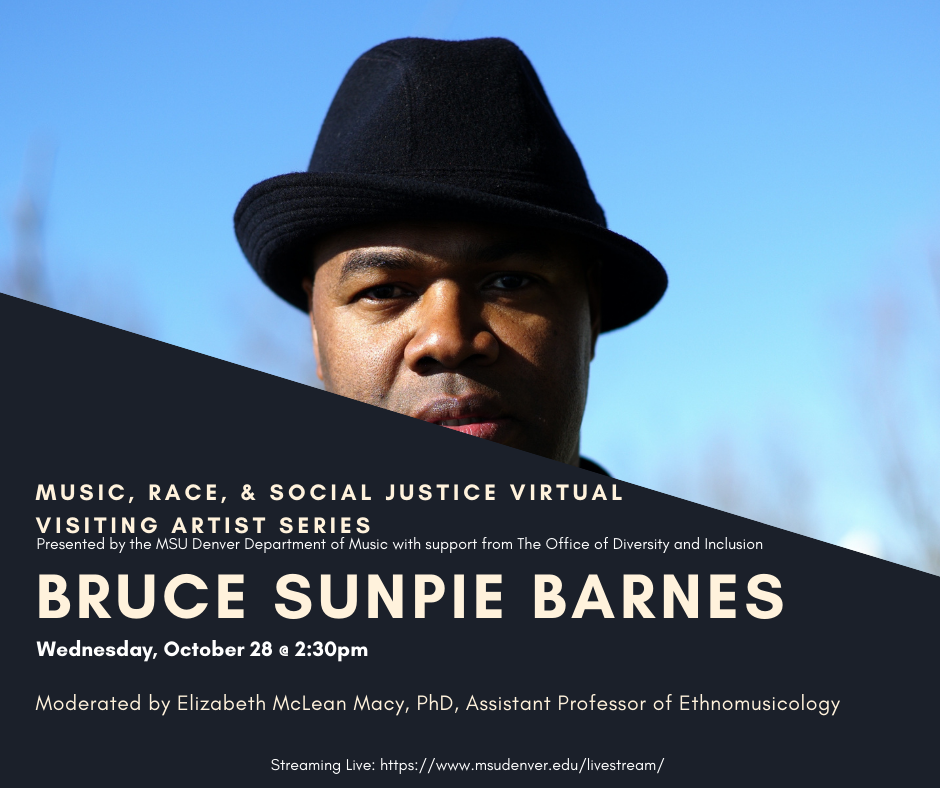

New Orleans musician, book author, ethnographic photographer, and member of the Black Men of Labor Social Aid and Pleasure Club and Big Chief of the Northside Skull and Bones Gang, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes — who joined us from New Orleans during a hurricane, bourbon and accordion in hand, for which I served as moderator:

And RAPtivist Aisha Fukushima, founder of RAPtivisim (Rap Activism) to amplify universal efforts for freedom and justice, for which Dr. Benitez reprised his role as moderator:

Spring 2021 events featured:

Hip-Hop artist, producer, activist, and scholar Olmeca, moderated by Dr. Chalane Lechuga, Associate Professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at MSU Denver:

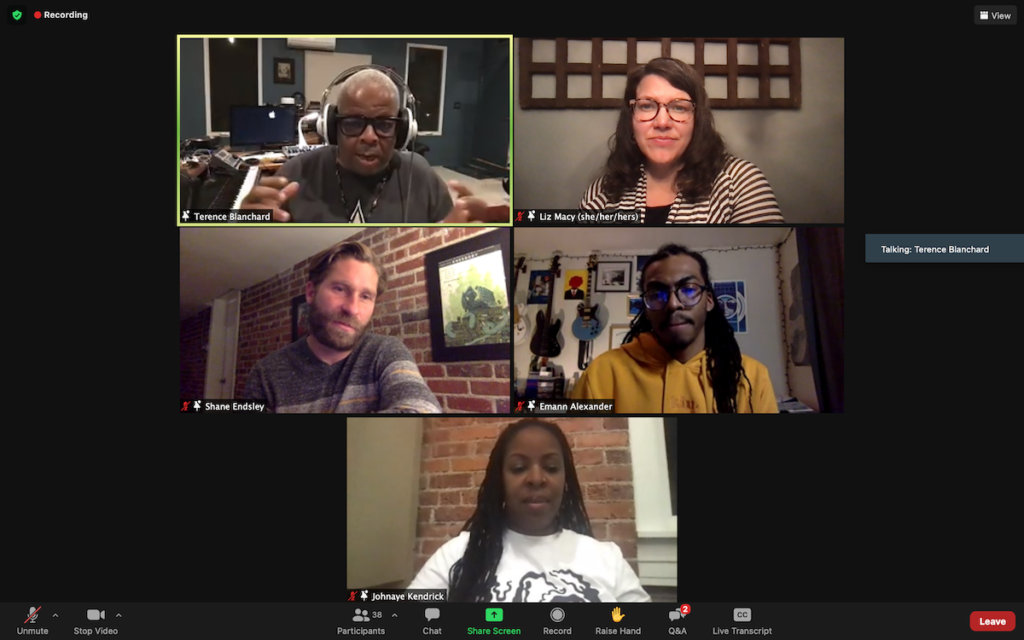

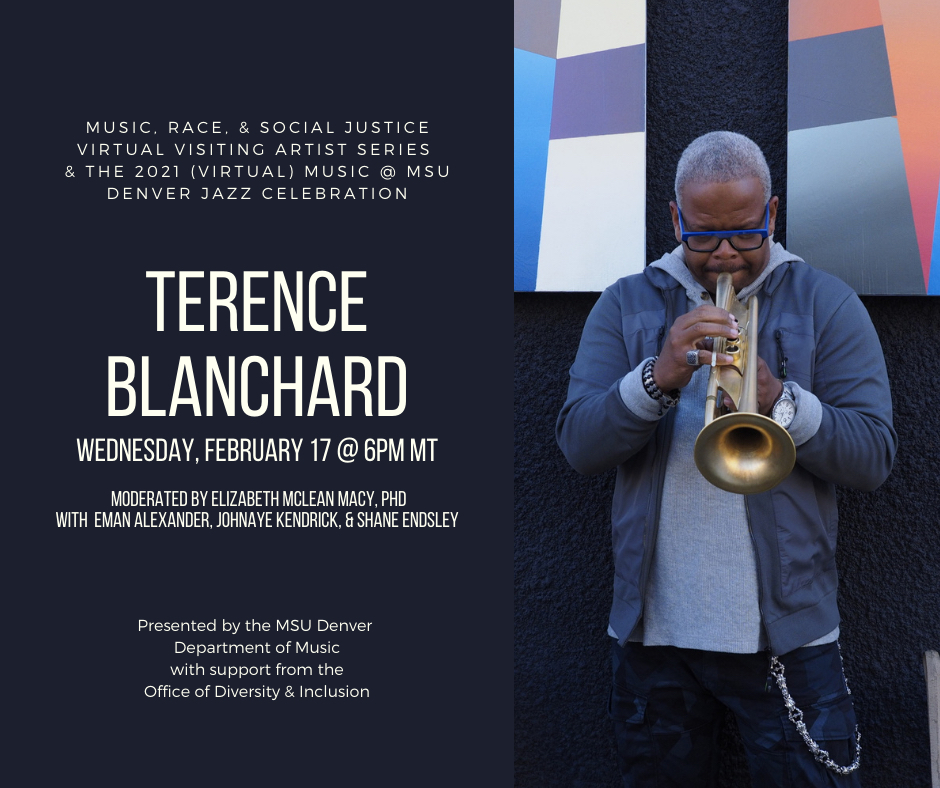

A roundtable discussion (for which I served as moderator) featuring trumpeter/composer Terence Blanchard discussing music and activism with special guests Eman Alexander (a MSU Denver graduate), Johnaye Kendrick (of vocal jazz quartet säje), and trumpeter and MSU Denver faculty in trumpet, Shane Endsley:

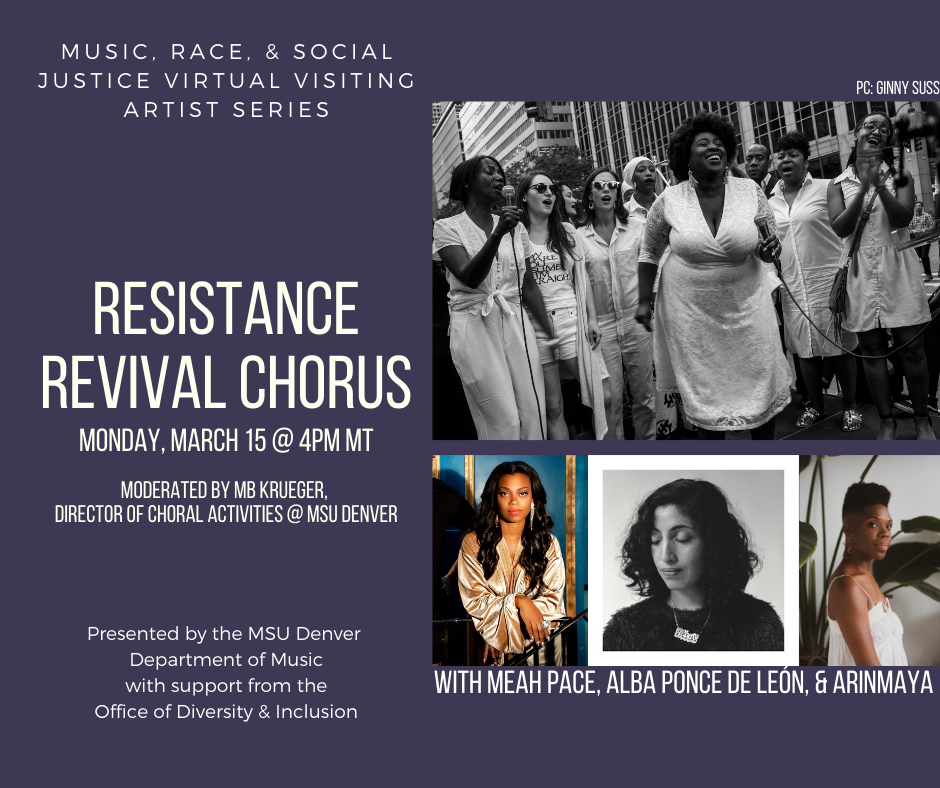

Members of the Resistance Revival Chorus, a collective of more than sixty womxn and non-binary singers who “join together to breathe joy and song into the resistance and to uplift and center womxn’s voices,” moderated by MB Krueger, our Director of Choral Activities, and joined by a panel of students and Denver-based singer Grace Clark:

The “People’s Hip-Hop DJ Scholar,” DJ Kuttin Kandi, one of the most accomplished womxn DJs in the world, moderated by Dr. Benitez:

And music educator Dr. Joyce McCall, who gave a talk titled “The Intersection of Race and Music: An Unsung Blues,” moderated by our Director of Music Education, Dr. Carla Aguilar:

Our 2020-21 visiting artists were drawn from multiple disciplines and approaches, from across the United States, bringing a breadth of experience and a wide range of approaches to activism and justice work in the arts. Knowing everything would be virtual, I had the opportunity to think big. But in constructing the series I also wanted to forge connections.

During the 2021-22 school year, I began to think about what it meant to create a sustainable series moving forward. Knowing that events would be in-person (and still archived and available via livestream for accessibility), the number of ten events of the previous year was out of the question. In Fall 2021 we hosted:

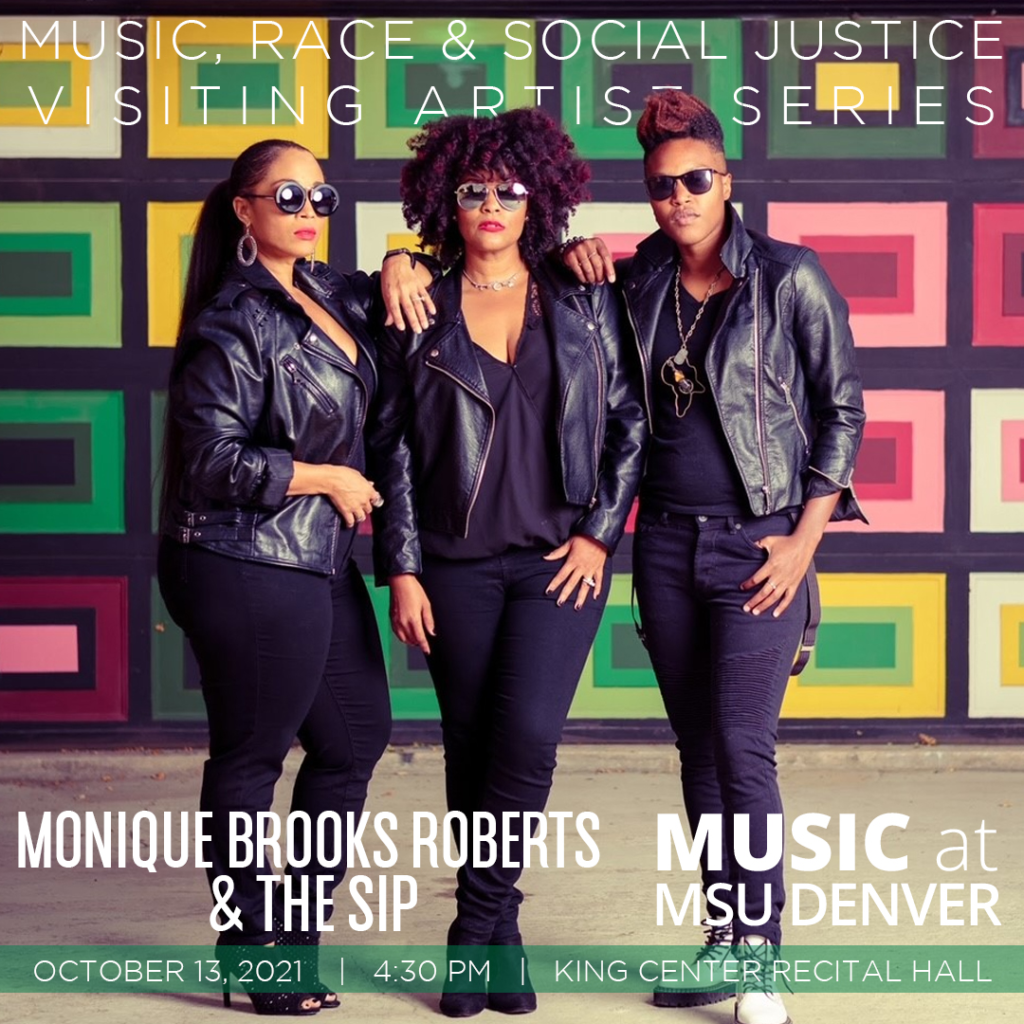

Denver-based soul/jazz fusion violinist Monique Brooks Roberts, who led a masterclass for our jazz and strings students and whose performance and talk featured singer Rajdulari and poet Kerrie Joy (both of whom co-host The SIP Podcast with Monique, a podcast that “centers the voices and experiences of Black women”). They were joined by moderator Joslyn Ford Keel (singer JoFoKe), a singer and songwriter who teaches in my department:

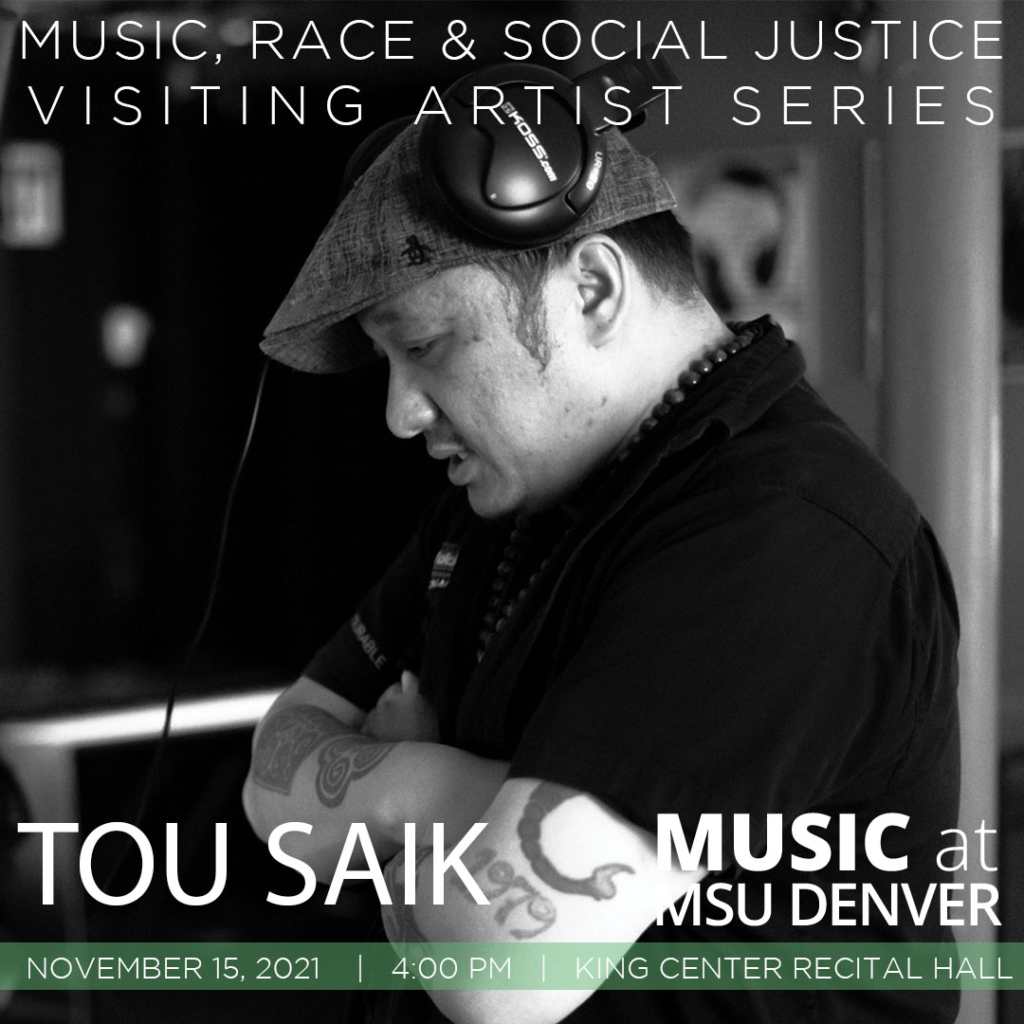

Hmong hip-hop artist, storyteller, and spoken word poet Tou SaiK Lee, who visited music and Africana Studies classes, led a songwriting workshop, and gave a performance/talk moderated by CU PhD Candidate in Ethnomusicology Benjamin Cefkin:

Spring 2022 was scaled back:

Roberts returned for an extended residency, working with our Jazz and American Improvised Music and Strings students, leading a Masterclass with her band, and attending and playing at our end of the year student jam session.

Balinese experimental duo ghOstMiSt performed an improvisational set of music and dance in conjunction with the Rocky Mountain Balinese Gamelan Festival:

While the 2022-23 series is still in the planning stages, I am working on collaborative events and residencies in conjunction with the departments of Dance and Africana Studies, as well as our Center for Multicultural Engagement and Inclusion.

Conclusion

Amplifying voices and representation is at the heart of the work that I’ve been doing at MSU Denver. Formulating, organizing, and carrying out this series has been an overwhelming experience in many ways. I’ve integrated the visiting artists into my classes (residencies mean that this will be a regular occurrence); students are asked to formulate questions for discussion and not only attend the events but also interact with our guests; I’m collaborating across my department and across disciplines (a relatively unheard of thing on my commuter campus); and the events draw global audiences (because of the livestream element). We maintain a department page devoted both to the series and the past livestreams, highlighting the series and the work it does. The performances and talks are inspiring, for many reasons, and students have been thrilled to see themselves in our visiting artists. Moreover, the intersections with other departments and community members are providing a way for our department to build bridges across disciplines and with our greater community, connections that will help us create those spaces “for everyone to play” that Kajikawa references.

Confronting the canonization of music on the podcast Still Processing, Professor of African American Studies Daphne A. Brooks says that “canons are about inequality. They’re about order and structure and power and exceptionalism rather than plurality.” Doing this work and considering how we can expand the canon, make space for a plurality of voices, or really change our expressive practices is not without its own challenges, but those challenges are the reason that this series (and others like this) matters. Academic institutions are often slow to change, despite evolving perceptions and ways of thinking. For me, doing this sort of work and providing these spaces for conversations and the sharing of ideas is about expansion and exposure. And the excited responses from students who see themselves in a performer — sometimes for the first time — prove that we need more visibility and intersectionality in what we present in the classroom and on the stage.

[1] Kajikawa, Loren. “The Possessive Investment in Classical Music: Confronting Legacies of White Supremacy in U.S. Schools and Departments of Music.” In Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindedness Across the Disciplines, edited by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (pp.155-74). University of California Press, 171.