Introduction

Kendrick Lamar’s third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly, was released in 2015 to critical acclaim and, with more than nine million streams within a week of its release, became one of the most listened to Hip-hop albums of that year.[1] In the context of Hip-hop’s withdrawal from the forefront of social discourse during the mid-2010s, when the Black Lives Matter’s hashtag activism and anti-police brutality protests were reaching a fever pitch, To Pimp a Butterfly debuted with brute force and has since lost none of its impact. [2,3] The emotionally charged album dissects the anger of Black youth within the context of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2012.[4] In fact, the album accomplished this so well that after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, protesters around the world used the album’s seventh track, “Alright,” as an anthem. When asked how he felt regarding the popularity of this song, Lamar said,

“I’d go in certain parts of the world, and they were singing it in the streets… When it’s outside of the concerts, then you know it’s a little bit more deep-rooted than just a song. It’s more than just a piece of a record. It’s something that people live by — your words.”[5]

Further, To Pimp a Butterfly’s incorporation of anti-racist ideologies found in other works by famous Black musicians, such as Boris Gardiner, Marvin Gaye, and Curtis Mayfield, builds on themes from Lamar’s previous albums, such as Good Kid, M.A.D.D. City (2012), and Section .80 (2011), transforming them into clearer, more upfront, and angrier statements targeted at the US government as well as white individuals who contribute to the perpetual mistreatment and circumscription of the Black community.[6]

In this article, I propose that Kendrick Lamar uses To Pimp a Butterfly’s roughly five-minute lead-off track “Wesley’s Theory” to expose the US government’s mediocre and meager attempt — if there ever was one — at establishing a firm foundation from which subordinate (Black) individuals can prosperously build. Through political satire and explanation of the dichotomy between what a Black man is “supposed” to be and what a Black man is, this album demonstrates that there is more to Black masculinity than meets the eye. I also argue that as listeners and consumers of Hip-hop, and as academics, we should approach the study of this genre as one requiring an in-depth and thorough examination. Engaging with Hip-hop is integral to understanding Black life, struggles, and identity. By analyzing “Wesley’s Theory,” I suggest that we take a multi- and interdisciplinary lens to further flesh out the many facets of this relatively young and ever-changing genre. To listen only superficially is to disregard the constant battles faced by a marginalized group of people whose music is the root of much of American popular culture.

Background: Kendrick Lamar and To Pimp a Butterfly

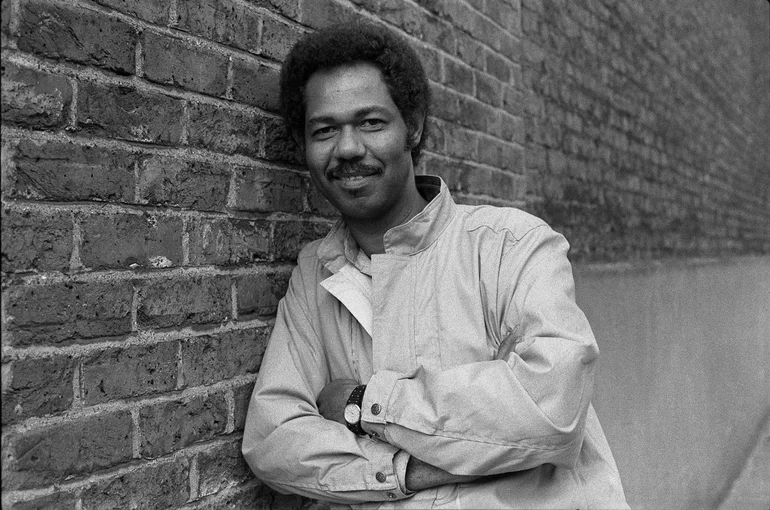

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth (born June 17, 1987, in Compton, California) rose to fame in 2003 with his mixtape Youngest Head Nigga in Charge, which was picked up by CEO Anthony Tiffith of the progressive rap label Top Dawg Entertainment. During this time, Lamar published his works under the pseudonym K. Dot. It was not until he released Overly Dedicated in 2010 that Lamar started using his first and middle name and gained immense popularity over the next two years. In 2012, Lamar was crowned the “new king of the West Coast” by The Game, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg.[7]

Already in his early albums, such as Section .80 (2011), Lamar rapped about the social and political issues faced by many in (but not limited to) the Black community, ranging from difficulty acquiring loans to limited attention for those in public housing to blatantly unfair treatment by the US government, such as the disparity of sentencing length in relation to petty crimes.[8] In “Fuck your Ethnicity,” Lamar talks about redlining, crime rates, government betrayal, and much more. That said, although Section .80 explores themes like those present in To Pimp a Butterfly (TPaB), the earlier album is geared more toward exposing structural racism while TPaB focuses more generally on Black life and identity.

Lamar discussed his two-year long writing process for TPaB in an interview with the creators of “The Making of Grammy-Winning Recordings,” a YouTube program in which a panel of music critics and appreciators interview creators of hit songs or albums. Tackling his insecurities and accepting his role as a leader were at the forefront of Lamar’s mind during the album’s creation, his overall goal being to “speak on things that [he] feels like people don’t have voices to speak on.”[9] One would think that Black men already possess the ethos necessary to dispel myths that they are not allowed to be vulnerable, but they do not. According to African American studies scholar Patricia Dixon, men in the United States (including Black men) often want to follow the script of being strong community defenders. Indeed, many Black men see themselves this way because these scripts are virtually everywhere — not only do broader social appeals to traditional gender roles support the trope of men as head-of-household, but cultural performances in television, film, and music videos reinforce the Black community’s perception that Black men protect Black people. Disproportionate police brutality against Black men, on the other hand, creates conflicting expectations of the place and role of Black American men both in their nation and in themselves: protectors of their community and yet unequipped to protect themselves.

Despite these contradictory social inputs, Black men continue to follow the script.[10] What is more, sociologist and author Herman Gray writes that, in the United States, self-representations of Black masculinity have been historically shaped by, and in opposition to, prevailing discourses of masculinity and race, particularly whiteness.[11] Lamar uses his music to consider why this idea is put into practice: Black men need to protect their communities because those who are put into power supposedly to help are, instead, causing harm. In white culture, the concept of man-as-provider is not stressed as much — white men have little to prove, since their ethos has already been established in society. Lamar elucidates Grey’s idea that Black men in the US have shaped their views of what masculinity is by doing the opposite of what “masculine” white men have done in the past.

Analyses of TPaB’s album cover alone speak to this contrary idea of masculinity and to the album’s intention to address structural racism in the context of US history. Freelance film journalist and BBC writer Ashley Clark raises the question of whether the title and cover of TPaB are loosely based on Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird. Clark writes: “[P]erhaps the dead judge on the album cover (who also bears a striking resemblance to Ronald Reagan) represents Judge John Taylor, a decent man who worked inside a broken system and couldn’t save Tom Robinson, the black man falsely accused of raping a white woman.”[12] Meanwhile, writer Steven Molina believes that the cover is a “visual of anger, [with] much of it stemming from the oppressive nature of capitalism of black workers and youth. Blacks finally get a platform on the white house lawn.”[13] I believe Molina’s perspective draws attention not only to the copious wrongdoings by the Reagan administration against the Black community (and its role in an ugly legacy of governmental devaluing of Black life) but to the critical work Lamar is doing to give agency to the Black community.

Analysis: Black masculinity and institutional racism in “Wesley’s Theory”

Cultural sociologist Antonia Randolph argues that because multiple factors play into the expression of masculinity for subordinate (Black) men, we must look at the intersection of race, class, and gender in order to legitimately understand Black masculinity.[14] This intersectional approach is useful for an examination of “Wesley’s Theory,” as the track’s lyrics allows listeners to develop an understanding of how institutional racism is embedded within the US government, and therefore formative for Black identity. Institutional racism, defined by its discriminatory practices or policies ingrained in corporate structures, is often more difficult to detect than interpersonal discrimination and can lead to divisions in socio-economic status, thereby creating a system that almost invisibly ostracizes a distinct group of people along lines of race and wealth. The myth of meritocracy thrives on this invisibility, and this is what Lamar seeks to illuminate in this song. In only two verses (in four minutes and forty-seven seconds) Lamar explains the struggles of having and maintaining wealth as a Black individual in the United States.

The lyrics of the track are as follows:[15]

[Intro: George Clinton] When the four corners of this cocoon collide You’ll slip through the cracks hoping that you’ll survive Gather your wind, take a deep look inside Are you really who they idolize? To pimp a butterfly [Hook: Kendrick Lamar] At first, I did love you But now I just wanna fuck Late night thinkin' of you Until I got my nut Tossed and turned, lesson learned You was my first girlfriend Bridges burned, all across the board Destroyed, but what for? [Verse 1: Kendrick Lamar] When I get signed, homie I'mma act a fool Hit the dance floor, strobe lights in the room Snatch your little secretary bitch for the homies Blue eyed devil with a fat ass monkey I'mma buy a brand new Caddy on vogues Trunk the hood up, two times, deuce four Platinum on everything, platinum on weddin ring Married to the game, made a bad bitch yours When I get signed homie I'mma buy a strap Straight from the CIA, set it on my lap Take a few M-16s to the hood Pass 'em all out on the block, what's good? I'mma put the Compton swap meet by the White House Republican, run up, get socked out Hit the Pres with a Cuban link on my neck Uneducated but I got a million dollar check, like that [Pre-Hook: Thundercat] x2 We should never gave, we should never gave Niggas money go back home, money go back home [Hook: Kendrick Lamar] [Break: Dr. Dre] Yo what's up? It's Dre Remember the first time you came out to the house? You said you wanted a spot like mine But remember, anybody can get it The hard part is keeping it, motherfucker [Verse 2: Kendrick Lamar] What you want you? A house or a car? Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar? Anything, see, my name is Uncle Sam I’m your dog Motherfucker you can live at the mall I know your kind (That's why I'm kind) Don't have receipts (Oh man, that's fine) Pay me later, wear those gators Cliche and say, fuck your haters I can see the borrow in you I can see the dollar in you Little white lies with a snow white collar in you But it's whatever though because I'm still followin' you Because you make me live forever baby, count it all together baby Then hit the register and make me feel better baby Your horoscope is a gemini, two sides So you better cop everything two times Two coupes, two chains, two c-notes Too much ain't enough both we know Christmas, tell 'em what's on your wish list Get it all, you deserve it Kendrick And when you get the White House, do you But remember, you ain't pass economics in school And everything you buy, taxes will deny I'll Wesley Snipe your ass before thirty-five [Bridge: George Clinton] Lookin' down is quite a drop (It's quite a drop, drop) Lookin' good when you're on top (When you're on top you got it) A lot of metaphors, leavin' miracles metaphysically in a state of euphoria Look both ways before you cross my mind [Pre-Hook] [Outro] x5 Tax man comin'

The track’s title itself refers to Wesley Snipes, esteemed Black actor and film producer who was sentenced to three years in prison in 2010 for evading tax collectors.[16] Expanding on what it means to, as the album title says, “pimp a butterfly,” the track articulates how racist American institutions uphold white supremacy by exploiting Black creators for profit, and it also tackles the perpetuated misinterpretation of Black masculinity. By incorporating song snippets, lyrical references, and peer discussion from rap artist Dr. Dre, funk musician George Clinton, lyricist Josef Leimberg, and Jamaican singer/songwriter Boris Gardiner, Lamar notes class status and discusses finding and maintaining success in the music industry.

The track begins with a sample from Boris Gardiner’s titular song “Every Nigger is a Star” (1974), which proposed a reclamation of the derogatory term “nigger,” intending to change previous ideologies surrounding the word and to take away its power from those who used it to establish dominance — namely, white people seeking to dehumanize Black people. By sampling this late twentieth-century song, Lamar calls attention to the ill-informed and ongoing belief system that the term’s use embodies: putting down a person simply based on race and preconceived (often implicit) biases.

Following the Gardiner excerpt, Lamar samples five lines from a conversation with 70s funk artist George Clinton as a reflective response.

[Intro: George Clinton] When the four corners of this cocoon collide You’ll slip through the cracks hoping that you’ll survive Gather your wind, take a deep look inside Are you really who they idolize? To pimp a butterfly

Butterflies have a history, in art, of representing femininity and daintiness. So, it is ironic to use a butterfly to symbolize a man — especially a Black man. Clinton insinuates that a tension exists between American society’s love for Black performers and our sense of their shared humanity — “pimp” is to exploit something while simultaneously showing it off, and the US has been pimping out Black people for centuries. It started with minstrelsy, and having Black individuals depict themselves as subordinate; it continues with popular stage shows like Showboat and Porgy and Bess. During slavery, Black individuals were often depicted as docile and manageable, which created — or rather, prompted — the belief that slavery was what was best for them.

It was W.E.B. DuBois who said that white people viewed freedom as something that would “spoil” and “ruin” Black people.[17] What “ruined” Black people was white Americans taking everything from them, forcing them to assimilate, and then, once a new Black cultural identity was established, degrading and diluting it until a rich, complex history is turned into a stereotype[18] — essentially, taking Black life, love, and happiness and pimping it out for profit. In “Wesley’s Theory,” the stereotype of Black men as pimps is turned on its head. White men are the pimps; the butterflies, in this case, are not women but fragile, vulnerable, and beautiful Black men, who do the crucial work of pollinating American music through their innovations in multiple genres.

In addition to the track’s more surface-level racial references, race is mentioned in subtle ways not easily discernible to those outside of Black culture. The lyrics “I know your kind (That’s why I’m kind)/Don’t have receipts (Oh man, that’s fine)/Pay me later, wear those gators…” and “I’ll Wesley Snipes your ass before thirty-five…” touch on assumptions made about Black men’s attire and their desire to succumb to high status — in this case, whiteness — by purchasing and flaunting luxury items; the lyrics also allude to Black men’s understanding (or lack thereof) of finances by referencing the 2005 tax scandal involving Snipes’ attempt at preserving wealth.

In this way, the track serves as sociopolitical satire. Lamar exaggerates the glorification of carnal desires, unhealthy habits, and poor money management — a widely held bias toward Black people with higher incomes — by splitting the song into two contrasting points of view: the first verse is from the perspective of Lamar (serving as the consummate Black musical artist discussing themes of sex, violence, and unruly spending), and the second verse is from the perspective of Uncle Sam, a well-known personification of the US federal government dating back to the early nineteenth century. Lamar uses Uncle Sam to present a harsh reality about the United States: the “American Dream” is unattainable for many individuals. Even Black people like Snipes, a talented actor and accomplished film producer, eventually run into financial difficulties despite their higher social status. Arguably the most important lines from the second verse are:

And when you get to the White House, do you

But remember, you ain't pass economics in school

And everything you buy, taxes will deny

I'll Wesley Snipe your ass before thirty-five

This snippet sheds light on the fact that many Black individuals struggle with financial literacy and, consequentially, wind up in financial trouble with little to no support.

In a 2019 Washington Post article, historian and Arizona State professor Calvin Schermerhorn states that the 1865 emancipation of Black individuals in the United States should have sparked a new era of Black wealth creation.[19] However, the wealth gap continues to grow. Furthermore, even as some members of the Black community have been able to accumulate wealth, they haven’t, in general, gained more social capital. Indeed, Lamar’s lyrics speak to not having power despite having money.[20] The second verse of “Wesley’s Theory” exposes how Uncle Sam justifies Black poverty through the idea that Black people won’t spend their wealth responsibly. This idea reminds us that, as sociologist Kelly Miller observes, “the [n]egro is up against the white man’s standard, without the white man’s opportunity…”[21] — even when Black people pursue the signifiers of success, racialized distinctions continue to obstruct their path to social (and literal) capital. Using juxtaposition and caricature, Lamar reveals these governmental justifications while showing his own hope to use his wealth not for debased and fleeting pleasures, but to rebuild his community.

The last few stanzas of the song respond to Uncle Sam, saying:

Take a few M-16s to the hood

Pass 'em all out on the block, what's good?

I'mma put the Compton swap meet by the White House

Republican, run up, get socked out

Hit the Pres with a Cuban link on my neck

Uneducated but I got a million-dollar check, like that

This short excerpt emphasizes very significant and specific ideologies in Black and African American culture: the importance of community and found family. Black cultural identity is multifaceted, with strong community and family factors influencing occupational choice. The overall goal is to protect what you have and never forget where you came from,[22] to use your money and power to uplift and protect those who got you to where you are today.

As academic musicology seeks increasingly to transcend musical or historical analysis — to understand through an interdisciplinary lens the importance music has to different groups of people — I argue that we should continue to strive to understand Hip-hop and Rap as a social and cultural practice. Foundational anthropologist Clifford Geertz defines culture as “a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life.”[23] “Wesley’s Theory” demonstrates such “inherited conceptions and ideals” in the context of Hip-hop and Black culture. In Black and African American culture, it is encouraged, if not expected, to take care of your family, including anyone and everyone you grew up around. As music listeners, we must do more than superficial listening to Hip-hop and Rap albums, EPs, and singles, not only because they potently express the legitimacy and complexity of Black reality in the US, but because they stand as outcries against the way that the US government treats its constituents.

Advancing in academia

In her article, “Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Beautiful: Black Masculinity and Alternative Embodiment in Rap Music,”[24] Randolph explains that a lot of the discourse surrounding Hip-hop and Rap is heavily focused on the genres’ use of violent imagery in pursuit of asserting dominance, noting that “[m]uch of the research on rap takes its aggressive, violent masculinity for granted” and doesn’t pay near enough attention to the role Black men have in society or how that role doesn’t encourage or even allow vertical mobility. Thus, the dominance that’s being asserted by Black male artists has little to do with moving up the social ladder.

Not only are Black men held back from social and financial advancement as a result of institutional racism, but they are rarely given the security or adequate space to grow and prosper outside of certain cultural stereotypes set in place by those outside of Black culture; and straying from those “guidelines” is frowned upon. For example, Black men who pursue careers in Hip-hop and Rap are expected to fit conventional models of artists in these genres. Hip-hop scholar and American studies professor Mickey Hess observes that “a consistent performed identity […] seems crucial to credibility.”[25] Hip-hop scholar Michael Dyson, furthermore, claims that “hip-hoppers construct narrative conventions and develop artistic norms through repeated practice and citation.”[26] This desire to maintain a performed identity (a “brand”) is critical to success in the music world. Not to mention, so many Black men feel the need to present themselves as secure individuals to compensate for their actual lack of security in life.

After reading these claims, I find myself wondering if there has been a shift from early Hip-hop and its ideals. In her 2008 book The Hip Hop Wars, Hip-hop scholar Tricia Rose notes that Hip-hop has become a “playground for caricatures of black ganstas, pimps, and hoes… and violent portraits of black masculinity have become rap’s calling cards.”[27] What is this “consistent performed identity,” and has it shifted over time to appease record labels and/or consumers? And are we as Hip-hop enthusiasts and scholars witnessing an attempt at a paradigm shift by studying the recent works of Kendrick Lamar? Artists in any genre presumably build on stylistic norms established and perpetuated by their predecessors; deviations from these norms is what creates change. Lamar’s work represents innovations that are shifting Hip-hop’s conventions, drawing attention to these negative calling cards by making them even more obvious. In this way, his music functions like a caricature piece, challenging listeners to face and to reconsider what they think they know about Black being.

Too often Hip-hop and Rap are looked down on for being violent or having violent themes when, actually, there is a justification for the violent imagery and lyrics: the systemic oppression faced by the Black community. Black men, commonly thought of as hyper-masculine and chauvinistic and exhibiting characteristics of “thugs” or “gangsters,” are rarely given the leeway to embody other identities. Tracks such as “Wesley’s Theory” allow us to challenge our implicit biases regarding themes illustrated in popular and mainstream Rap and Hip-hop. What does it mean to be a “gansta” or a “thug”? Who is to blame for the lack of vertical movement amongst Hip-hop artists? What do we do with the foundation Lamar has laid out for us as consumers? Lamar’s use of stark and violent poetic imagery challenges conventional norms of social propriety, Black masculinity, and the politics of racial oppression in urban American society, which is why Hip-hop is a genre of music that is valuable and culturally relevant. In a very fundamental sense, music, as a cultural practice, has always been a way to convey feelings and emotions that are otherwise hard to explain, and the passing down of songs and regulations from generation to generation as well as the use of music for specific social events is critical. These genres are no different — Hip-hop/Rap study is valid and should be studied and celebrated accordingly.

As academics and music consumers, we must be comfortable enough to discuss what we don’t know, without fragility or fear of persecution getting in the way, in order to gain knowledge on topics that are important to all sectors of society. While many institutions are striving to incorporate Hip-hop studies in academic study, this is most commonly done in departments like sociology, anthropology, linguistics, and African/African American studies. By dissecting the systemic oppression that leads to scripts for Black masculinity, my analysis of “Wesley’s Theory” demonstrates just one part of the discourse we should be having about Hip-hop/Rap music; and I believe that music units across academia can do more to integrate Hip-hop/Rap studies into our curricula.

[1] Molina, Steven. “The Significance of Kendrick Lamar’s to Pimp a Butterfly.” Socialist Alternative, February 16, 2016. https://www.socialistalternative.org/2016/02/16/retrospective-significance-kendrick-lamars-to-pimp-butterfly/.

[2] Blair, Robert. “’To Pimp a Butterfly:’ How Kendrick’s Masterpiece Changed Culture.” THE (TO PIMP A) BUTTERFLY EFFECT – HOW KENDRICK’S MASTERPIECE CHANGED CULTURE, LIVES AND CAREERS. Highsnobiety, March 24, 2020. https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/kendrick-lamar-to-pimp-a-butterfly-analysis/.

[3] He continued making critical music in this vein, winning a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for his album DAMN. (2017), a groundbreaking moment which pushed along the conversation about the academic validity of Hip-hop and other “trending” genres.

[4] Molina, Steven. “The Significance of Kendrick Lamar’s to Pimp a Butterfly.” Socialist Alternative, February 16, 2016. https://www.socialistalternative.org/2016/02/16/retrospective-significance-kendrick-lamars-to-pimp-butterfly/.

[5] ibid.

[6]

[7] Bauer, P.. “Kendrick Lamar.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 19, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Kendrick-Lamar.

[8] Nellis, Ashley. “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System.” The Sentencing Project, May 1, 2018. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/.

[9] Lamar, Kendrick. “The Making of Kendrick Lamar’s ‘To Pimp a Butterfly.’” GRAMMY.com. Recording Academy, August 27, 2020. https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/making-kendrick-lamars-pimp-butterfly.

[10] Dixon, Patricia. African American Relationships, Marriages, and Families: An Introduction. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge, 2017.

[11] Gray, Herman. “Black Masculinity and Visual Culture.” Callaloo 18, no. 2 (1995): 401–5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3299086.

[12] Clark, Ashley. “Kendrick Lamar’s to Pimp a Butterfly Album Cover: An Incendiary Classic.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, March 11, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/mar/11/kendrick-lamar-to-pimp-a-butterfly-album-cover.

[13] Molina, Steven. “The Significance of Kendrick Lamar’s to Pimp a Butterfly.” Socialist Alternative, February 16, 2016. https://www.socialistalternative.org/2016/02/16/retrospective-significance-kendrick-lamars-to-pimp-butterfly/.

[14] Randolph, Antonia. “‘Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Beautiful’: Black Masculinity and Alternative Embodiment in Rap Music.” Race, Gender & Class 13, no. 3/4 (2006): 200–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675181.

[15] songlyrics.com

[16] VanHoose, Benjamin. “Wesley Snipes Says He ‘Came out a Clearer Person’ after Serving Prison Time for Tax Evasion.” PEOPLE.com. People Magazine, November 2, 2020. https://people.com/movies/wesley-snipes-reflects-prison-time-tax-evasion/#:~:text=The%2058%2Dyear%2Dold%20actor,was%20released%20in%20April%202013.

[17] Dubois, William Edward Burgehardt. “The souls of black folks.” Society 28, no. 5 (1991): 74-80.

[18] Barkman, Erick. “Pimpin’ Pimps: Explaining the Presence of Pimps in Hip-Hop Culture.” Theorizing Rituals, Volume 1: Issues, Topics, Approaches, Concepts 3, no. 1 (2006): 321–43. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047410775_015.

[19] Schermerhorn, Calvin. “Why the Racial Wealth Gap Persists, More than 150 Years after Emancipation.” The Washington Post. June 19, 2019.

[20] ibid.

[21] Eisenberg, Bernard. “Kelly Miller: The Negro Leader as a Marginal Man.” The Journal of Negro History 45, no. 3 (1960): 182–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/2716260.

[22] Stanford, Nyla, Shelby Carlock, and Fanli Jia. 2021. “The Role of Community in Black Identity Development and Occupational Choice” Societies 11, no. 3: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030111

[23] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Clifford Geertz.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 26, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Clifford-Geertz.

[24] Randolph, Antonia. “‘Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Beautiful’: Black Masculinity and Alternative Embodiment in Rap Music.” Race, Gender & Class 13, no. 3/4 (2006): 200–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675181.

[25] Hess, Mickey. (2005). Hip-Hop Realness and the White Performer. Critical Studies in Media Communication – CRIT STUD MEDIA COMM. 22. 372-389. 10.1080/07393180500342878.

[26] Dyson, Michael Eric, Jay-Z, and Nas. Know What I Mean?: Reflections on Hip-Hop. New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2010.

[27] Rose, Tricia. “Introduction.” Introduction. In The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop and Why It Matters, 1–2. New York, NY: BasicCivitas, 2008.