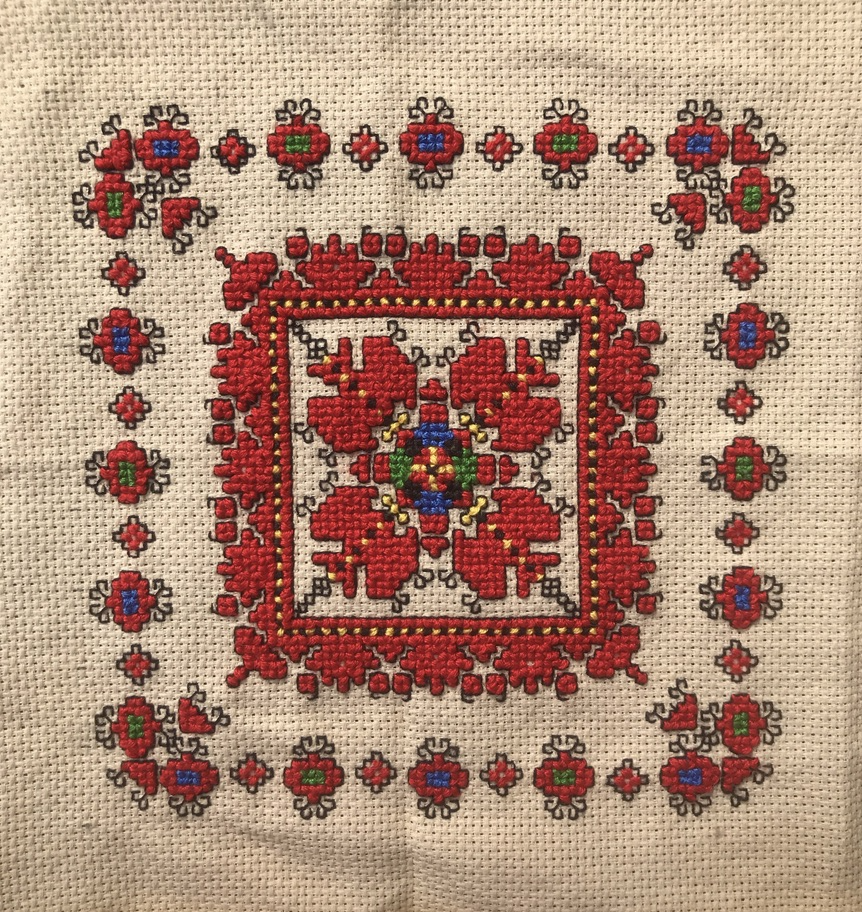

My thirty-something friend, Zori, runs a small business in Bulgaria collecting traditional folk costumes and renting them to brides and grooms for their wedding days. Traditional premodern weddings are coming back into style, with couples wearing folk costumes and performing select ritual reenactments as part of their wedding ceremonies.

My other friend, Bobi, who holds an impressive knowledge of Bulgarian traditions and customs, dislikes these weddings. She bases her dislike on their selective incorporation of revived ritual elements into the contemporary wedding ceremony.[1] She sees these new reenactments as performative, lacking the authenticity and symbolism that she believes such rituals used to hold, when the reenacted practices were part of a fully integrated semantic system.

As a folklorist, I am wont to remind her that all performance of tradition is selective. Indeed, many of the naturalized elements in contemporary weddings are out-of-context carryovers from past meaning systems that we simply don’t question (as they are in wedding ceremonies around the world). This is what keeps traditions alive: the comingling of what Barre Toelken calls the “dynamic” and “conservative” elements of tradition, or what Henry Glassie calls the “creation of the future out of the past.” Tradition is about the future.[2] We keep the elements that matter to the group to whom the practice belongs, and we discard the aspects that no longer appeal to the group. This is how variation enters our cultural practices, contributing to their vitality over time.

As young couples revive elements of wedding rituals, they adapt the elements to fit their contemporary needs. This is seemingly the folklore process at work, but my friend Bobi is correct in some senses — this is not what a folklorist would call a living tradition. Rather, it is more akin to what we would call folklorismus, or folklorism: the conscious performance or recontextualization of previously “naïve” or self-evident traditions.[3] Still, this does not mean the wedding practices Bobi dislikes are not real nor meaningful. To understand this meaning, though, one must move past the fixation on whether the cultural practice is authentic. Instead, a much more interesting exploration would pay attention to the use of tradition: in this case, the ways these young couples creatively use folklore as a resource.

I think of this phenomenon as the “turn to folklore.” This “turn” is not necessarily new, nor is it happening only in wedding ceremonies. From foodways to folk dance troupes to folk choirs, such practices are increasingly visible across life in contemporary Bulgaria and beyond. In the American context, for example, we’re all drinking from Ball glass jars again and making homemade bread. Several scholars are documenting a mushrooming of folk schools across North America.[4] What should we make of the growing popularity of these practices, in which people turn to folklore to contextualize contemporary life, show a preference for old aesthetics, and recuperate practices that have fallen by the wayside?

To poke into some of these appearances — and their consequences — I turn to two sources that are already thinking through the turn to folklore in creative ways, in the Bulgarian context: Georgi Gospodinov’s highly acclaimed new novel, Time Shelter (2022, translated by Angela Rodel), and an Instagram account, “Momata Barbi,” (in essence, a Bulgarian-style Barbie Girl). Both present somewhat irreverent takes on the presence of tradition and ritual in contemporary life, and both present fictionalized but reasonable experiments with the folkloric that resemble these new takes on traditional weddings. This article gives a preliminary exploration of art forms in which creators are processing the implications of visible turns to folklore. I discuss this novel, social media persona, and IRL trend of ritual weddings, offering some thoughts and suggestions to guide encounters with folklorism beyond Bulgaria. By doing so, my hope is to demonstrate for readers how they, too, might process uses of the past in their everyday lives.

Time Shelter

When I first read Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter, I had picked up the book for fun. I finished it, however, with a pen in hand. I was intrigued by a few scenes in which folk costumes are worn by the masses in daily life, and I needed to think about the uncanny resonance between the fictional world Gospodinov creates and the one I’d been observing in my own research in Bulgaria. To gloss a very complicated narrative, the book explores what might happen if, indeed, we turned back the clocks to the periods so desired by politicians, constituents, and nostalgic dreamers who long for already-lived pasts, glorious or otherwise. At a time when so much of the progress toward social justice, freedom of movement, and equity (broadly speaking) gained over the last half century seems in question, this novel contextualizes the “turn to tradition” within a larger political moment. In Gospodinov’s novel, practices like the ritual weddings my friend Bobi observes are not just a trend but serve as plot points that gesture toward a loss of faith in our capacities to thrive within a fraught present and an unknowable future. Here, I’m not reviewing the book, but rather looking specifically at its attitude toward the growing presence of blatant revival.

Broken into five parts, the novel’s central plot follows narrator G.G. (who may or may not be Georgi Gospodinov himself) and his time-hopping collaborator, Gaustine. Both Bulgarians living abroad, the two men create a “clinic of the past”: a ward of meticulously curated rooms, the décor, scents, and sounds of which emulate various decades of the twentieth century, designed as a treatment center for Alzheimer’s patients. Much like a hospice service, the clinic does not serve to heal, but rather to indulge and encourage a comforting environment for patients to dwell within chosen memories, real or constructed. By compelling readers to recognize the dignity found in having agency over how we spend our final days, the story of this clinic at first challenges the notion that all backward glances are necessarily misguided.

As the clinics gain notoriety, however, a kind of nostalgic craze grips Europe and the emergent “time shelter” treatment model spreads from the personal scale to the social. National folk costume becomes the norm for streetwear and European Parliament members alike, with one nation’s minister of defense riding a horse to office while wielding a saber. Eventually, inevitably, this trend becomes nationalized and politicized as the pockets of performative dress inspire a top-down, officially sanctioned European Union “Referendum on the Past.” Member states vote to select a decade to which they will collectively reset, grappling with the choice between the known joy they’ll return to and the known pain that will come after the era they’ve selected; no golden era reigns indefinitely.

Spain elects to return to the post-Franco bliss of the 1980s. The Czech Republic selects the 1990s, just after the Velvet Revolution. Switzerland maintains neutrality by “returning” to the exact moment of the Referendum, choosing the past that is the present just lived. As grand historical moments both celebrated and reviled roll around once again (such as Bulgaria’s failed April Uprising and the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand), the line between reenactment and reality blurs with dire, deadly consequences. This is Time Shelter at both its most speculative and its cleverest, taking a ridiculous leap from contemporary EU bureaucratic in-fighting to a tantalizingly plausible retreat to the “safety” of the past, to the devils that are already known.[5]

Quick-witted, dark, and self-deprecating, Time Shelter is written through the dual perspective of a well-traveled novelist raised on the margins of Europe, who offers insights into the interplay of center and periphery that seem to both critique and indulge nostalgia in its varied forms. The novel diagnoses the appearance of folk costumes (among other indicators) as a symptom of a reality we are already living, in which such practices signal unhealthy relationships to time as harbingers of greater problems to come. Indeed, in the present day, folk costume motifs are stylized as kitsch on t-shirts and accessories, traditional dance and folksong are being recuperated as fusion music, and, as noted above, full costumes are worn for weddings. Beyond noting such trends, we must ask, what are the political conditions concurrent with the growing popularity of these folklore uses that Gospodinov is writing against?[6]

Though a dramatized absurdity, Gospodinov’s Referendum speaks to a growing nationalist fervor that diagnoses the turn to the folkloric as dangerous, a symptom of something for which we should be on the lookout. Having completed the novel just one month before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, he astutely catches the pulse of something that has continued to fester. At the same time, my sense is that Gospodinov intends for his readers to recognize that relationships to the past are not straightforward. In the acknowledgment section to his text, Gospodinov unabashedly describes himself as a “person who loves the world of yesterday.” Indeed, his broader career showcases complex musings on the periods through which our societies have been transformed.[7] His relationship to time is one that holds space for complexity without easily settling into the binary of good and bad. Nevertheless, it is all too easy to read the “turn to folklore” in his novel as a plot point meant to signal problems on the horizon.

I sympathize with Gospodinov’s observation that folklore can be manipulated for ill purposes. Indeed, much harm has been done in the name of tradition and heritage. As a prime example, we should note with alarm that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting, ongoing war is predicated on contested heritage claims. Yet, as a colleague of mine recently stated, folklore is not inherently national, but is foremost local and regional.[8] State leaders (among others) utilize heritage narratives to craft national messages, manipulating claims to heritage for political gain. I, too, feel worried about the wobbling, hierarchical project that is the EU, and I am concerned by genocide unfolding within Europe’s borders.

Even so, the assumption that folklore — and even the recontextualization of folklore as folklorism — is always a sign of rot is too simplistic; such assumptions miss emergent meanings at the grassroots that often challenge state-level rhetoric. Because Gospodinov is a master observer, I hold no illusions that he misses the complexity of bringing costuming into contemporary life, nor do I wish to suggest that only a singular message of warning can be read from his text. In fact, I must remind myself that his novel is in some ways an act of play. I would nudge readers to question presumptions we might too easily take away from Gospodinov’s play on folklore motifs and revitalized practices encountered in real life. I invite us to recognize that uses of the past do not always signal nostalgia and nationalism run rampant, and that to presume so would be naïve. Instead, we might read Time Shelter as one of many creative works trying to parse the meanings of the folkloric through creative exploration.

“Momata Barbi”

The Instagram account “Momata Barbi” (Maiden Barbi or Barbi Girl) offers another look at the play on folklore. For those woefully not in the know, Momata Barbi is a treasure for followers of all sorts. With over nine thousand followers and two hundred-plus posts to date, the account documents the adventures of its namesake, Momata Barbi, in her daily life as a self-described “non-traditional traditional Bulgarian girl.” Diana Petrova, the young Bulgarian woman responsible for the account, created the idea while living abroad in Belgium during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inspired by a longing for home, she used Momata Barbi to explore traditional Bulgarian life, an aspect of the past and contemporary Bulgaria with which she was largely unfamiliar.

Depicting Barbi’s adventures around Bulgaria, Diana’s posts muse upon the joy of observing seasonal rhythms in her rural existence and celebrating the beauty of her homeland. Like some of Time Shelter’s characters, Barbi dresses herself in handmade national costume while living in the present day. She preserves her own foods, works to expand her repertoire of textile practices like knitting and felting, and participates in calendrical rituals. It is unclear if Barbi grew up in the village, or if she (like a growing number of young adults in Bulgaria) has moved to the village to build a new life outside of the normative urban path. Personally, I interpret her as a city-to-village migrant. She seems to fare well on adventures that take her into the city, and she seems at ease as a traveler to Bulgaria’s most notable sites, yet she’s always relieved to return to bucolic solitude. Plus, she’s eager to own a cow one day — most born-and-raised villagers are rarely so eager about the weighty responsibilities of owning livestock.

Far from being a docile maiden, Barbi is quite independent. This girl parties. She goes to bed drunk, and she wakes up craving a tried-and-true East European hangover cure: tripe soup. She “speaks” the cultural vernacular of her followers, curating an influencer-like account that is highly legible for those sharing her background. Unlike many accounts, books, and articles celebrating Bulgaria, Momata Barbi is decidedly not written in a nationalist frame. Her celebrations of Bulgaria’s natural wonders never revere the nation. In fact, she sometimes engages in skeptical discourse with the national past that many Bulgarians unquestioningly celebrate. For instance, while gazing at the Shipka monument to the liberation of Bulgaria, Barbi reflects that her freedom and happiness came at the expense of others and questions the supposed freedom these monuments represent (“O Shipka, are we still free?”). She ponders “the future revolution” with a statue of Vasil Levski, a Bulgarian revolutionary. There is a dialogic layering and movement between the stories of these noted, great places in the Bulgarian collective historical narrative and Barbi’s experience of them as an independent young woman. I would call her a patriot, but not a nationalist: she recognizes Bulgaria as her home, and she finds comfort in its traditional spaces and ways of life without ascribing these comforts to national glory. Bulgaria is the bounded space with which she is familiar.

Though she holds a penchant for the old ways, Momata Barbi engages in contemporary civic and political discourse. Barbi is vaccinated against COVID-19, and she urges her followers to vote. Both are notable acts in a country with a high rate of skepticism toward the democratic process and one of the lowest vaccination rates in the European Union. Wrapped in a rainbow flag, she marches in Sofia Pride in support of LGBTQ+ rights, where doing so is still relatively taboo. She defends Roma families as conscious recyclers, challenging tropes which position them as thieves or trash collectors, and she draws attention to poor urban housing conditions. Her actions communicate that true patriotism demands civic engagement, rather than disengaged rural retreat.[10]

Most notably, Momata Barbi challenges the mantle of tradition as an unchangeable mandate fixed everlastingly by an all-commanding past, clearest in her interactions with gendered traditional practices. Barbi clarifies that she is not making beautiful textiles for a dowry as her neighbor assumes, nor is she cooking for the young men in her village. In fact, she likes to beat the young men at their own game, participating in male-only rituals and doing so better than the boys.[11] According to some of her followers, Barbi is a fierce feminist, though she and her creator sidestep this framing in interviews about the project. Diana explains that her intent is to instead model a strong kind of young woman who pursues life as she pleases. Accordingly, many of the posts covertly or obviously explore Barbi’s desire to remain an independent girl, intertwined with nature rather than with a partner. When followers suggest she find a man, she builds a snowman. She charts her love affair as the bride of the Black Sea. She asks, what if I am in love with lyutenitsa?[12, 13]

I read this account as offering a rich site for exploring both traditional practices and forms in all their multiplicities, as well as one’s place within the broader scope of tradition. Unlike Gospodinov’s exploration of the turn to the past (more specifically, the institutionalization and appropriation of the past) as a dangerous precursor to something sinister, the affectations and personal authenticity of cultural traditions for Momata Barbi are on full display, highlighting meanings that clearly resonate at a scale beyond simply the national. Though Momata Barbi is dialed into the nationally bounded local, her civic engagement demonstrates an awareness of global conversations while it critiques an unquestioned idea of linear progress as the only path. Momata Barbi’s posts, as well as her gentle interactions with commenters, prompt discourse about traditions, adaptation, and sustainability. In ways that a novel cannot as easily create, the account provides a discursive space within which followers can work out how they might re-envision their own meaningful practices, pushing the boundaries of what it means to be “traditional” in contemporary life.

Conclusion

We have three depictions of the turn to folklore that we must contend with: traditional weddings as a modern trend, folk costume as a symptom of nationalism, and traditional lifeways as a plausible reality for a young, contemporary woman. Are these presences incompatible? What do they signal?

Georgi Gospodinov’s novel, Time Shelter, plays with the idea of national attitudes toward time (and their international reverberations), leaving readers with little doubt that the past does indeed have arms, and that the embrace of these arms is not to be fully trusted. In the American context, we are grappling at present with our own long-armed nostalgia, fracturing society into factions that could very much be diagnosed as temporal aspiration to escape the problems we have made for ourselves. Beyond the novel’s cleverness and rich prose, this resonance accounts for some of its wide appeal. It is onto something.

But folklore does not always signal a problem. As a folklorist who studies intergenerational relationships to traditional folklife, I closely follow the relationships of young Bulgarians to cultural heritage and their uses of the past in personal, civic, and nation-building projects. Often, their relationships to the past tend toward the playful, the curious, and the exploratory. For many of the young people I have interviewed, the “traditional” and the folkloric offer options outside of the turbulent, exploitative, and unsustainable presents they perceive within an unquestioned upward mobility that feeds into the failed promises Europeanization was supposed to offer. These young people are sometimes nostalgic — even problematically and inexplicably so — for lives they have never lived, but theirs is a nostalgia that often looks much more like Momata Barbi’s, rather than the scene of costuming nationalists depicted by Gospodinov’s novel.[14]

As Gospodinov shows us, we should of course be on guard for seepages between helpful and harmful. We might further recognize that both Gospodinov and Diana (the hand behind the doll) possess dual perspectives as East Europeans informed by international travel to the West. The international affords a new gaze on the national and, by extension, a new gaze on practices that have been tied to the national narrative. Notably, this is a perspective held by two creators who must grapple with both Europe’s centers and its peripheries, and thus hold the capacities to see the cracks in the system.

I want to be clear: I believe both the curiously playful, resistive folklore and the nationalist, xenophobic invocations of folklore exist, and they often look similar. What I am advocating for is careful attention to the processes that produce the folkloric, an awareness of the possibilities that the turn to the traditional might create, and the agency of the people working with tradition. I am by no means the first writer to call for complexity in our readings of folklore. My colleagues continually parse such nuances as new forms emerge. Scholars of folksong, folk dance, and traditional hybrids in particular offer excellent close readings of folklorism and folklore revival in contemporary East and Central Europe.[15]

In conclusion, I return once again to Zori, Bobi, and contemporary performances of ritual weddings in Bulgaria. Without more careful empirical study, it is difficult to say why, exactly, a young man might ritually shave the beard he’d already shaved five days ago, or why his bride-to-be would rather wear a rented hand-woven costume embroidered in ethnographic motifs than a new, crisp white dress. Without asking them, we can only guess at what these couples desire from tradition, invoked through folklorism. What we do know is that something about their present condition is causing them to turn to other resources: different aesthetics and relationships to tradition beyond those available to them in the present. We also know that they know that they are playing around with tradition. They know the groom has shaved before, for example, and are aware of the inconsistencies in this creative merger between past and present. They are not ignorant of these inconsistencies. This is the interesting part, to my mind.

Momata Barbi, the traditional weddings, and Gospodinov’s parallel universe all resemble one another, but they require us to ask different questions. The surprising aspect of folklorism is not the presence of folklore in contemporary life, nor the fact that the folkloric is not neutral. The past is regularly used rhetorically and strategically in ways that create division between groups, enforce boundaries, and engender exclusion. We know this. What’s more surprising — and more interesting — is the inventive use of tradition as a tool for creating the futures we are uncertain about.

In all three examples, we should recognize a playful (as opposed to reverent) attitude toward the past. The ability to use the past to explore issues of the present is an imaginative tool for people who are parsing disappointing, threatening, and disheartening presents. We would do well to acknowledge the complex creative work done by the people who merge past, present, and future. Further, we can recognize that the inclination to play with time in this way is shared by all of us. With this in mind, we can all more carefully make sense of the past as a driving force shaping the futures we’re forever moving toward.

Notes

[1] For example, Bobi notes that she finds it silly that men partake in the ritual of shaving their beards (brichene or brusnene) in contemporary weddings because this isn’t really the first shave (as is traditional). She uses the phrase “festive life” to explain that these practices are out of place, like a performance or drama instead of real life. For more on these weddings, see https://bnr.bg/en/post/100670361/authentic-bulgarian-weddings-back-in-vogue

[2] Toelken, Barre. The Dynamics of Folklore, Logan: Utah State University Press, 1996, and Glassie, Henry. “Tradition.” The Journal of American Folklore, 108: 430, Common Ground: Keywords for the Study of Expressive Culture (1995), 395-412.

[3] To be sure, folklorism and the authenticity of cultural tradition rouse a long tradition of debate in folkloristics. At present, folklorists generally read traditional practices that fall in the “folklorism” realm as postmodern synchronizations of authentic and staged traditions. See Bausinger, Hermann. Folk Culture in a World of Technology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [1961] 1990; Bendix, Regina “Folklorism: The Challenge of a Concept.” International Folklore Review 6 (1988), 5-15; Dorson, Richard M. Folklore and Fakelore. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976; Handler, Richard and Jocelyn Linnekin. “Tradition, Genuine or Spurious” The Journal of American Folklore 97: 385 (1984), 273-290; Handler, Richard. Nationalism and the Politics of Culture in Quebec. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988; Kirshenblatt Gimblett, Barbara. “Mistaken Dichotomies.” The Journal of American Folklore 101: 400 (1988), 140-155; Roginsky, Dina. “Folklore, Folklorism, and Synchronization: Preserved-Created Folklore in Israel.” Journal of Folklore Research, 44:1 (2007), 41-66; and Šmidchens, Guntis. “Folklorism Revisited.” Journal of Folklore Research, 36: 1 (1999), 51-70.

[4] See, for example, Totten, Kelly. Making Craft: Performing an Idea of Craft at U.S. Folk Schools. PhD Dissertation, Indiana University, 2017.

[5] Paralleling this plot, Gospodinov intertwines a metanarrative of G.G.’s journey (which we might read as Gospodinov’s own) to untangle his relationship to time, space, and memory. A number of fine reviews expand on Gospodinov’s exploration of individual and collective history, as well as the text’s relation to the traumas of the twentieth century. I direct the reader to their eloquent discussions on the interplay between authorial voice and fictive invention.

[6] I thank Christine Pardue for the push to make this question more explicit and for the lovely wording printed here.

[7] Gospodinov’s works include short story collections and novels, as well as the collaborative project I Lived Socialism: 171 Personal Stories, a Bulgarian-language collection of personal narratives depicting life under socialism. Ivanova, Diana, Georgi Gospodinov, Kalin Manolov, and Rumen Petrov. Аз Живях Социализма: 171 Лични Истории. [I Lived Socialism: 171 Personal Stories], 2006.

[8] These reflections were shared by my colleague Jeanmarie Rouhier-Willoughby (University of Kentucky), in a panel addressing the War against Ukraine at the 2022 Annual Meeting of the American Folklore Society in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

[9] For a wealth of ethnographic case studies exploring Urban-Rural migration, see the special issue of Bulgarian Ethnology: Migration from the City to the Village. 48:1 (2022) co-edited by Violeta Periklieva and Desislava Pileva, as well as a number of essays by Deema Kaneff that examine changing attachments to rural Bulgaria.

[10] See Marinov, Nikolay and Maria Popova, “Will the Real Conspiracy Please Stand Up: Sources of Post-Communist Democratic Failure.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1, (2022): 222-236. doi:10.1017/S1537592721001973 and https://minorityrights.org/minorities/roma-2/ for more information regarding the Roma in Bulgaria.

[11] For example, Barbi hides on Lazarovden because she doesn’t want to be coupled up. A commenter writes, “be free and queer, Barbie.” She dresses in pants and rides a horse on Todorovden, a practice typically reserved for men. She steals the village chicken on Petlyovden, so it isn’t slaughtered by the menfolk. She beats the menfolk in the Ivanovden river race to catch a cross.

[12] See “Момата Барби в народна носия, която популяризира българските обичаи,” https://ladyzone.bg/videa/btv-video/momata-barbi-v-narodna-nosija-kojato-populjarizira-balgarskite-obichai.html

[13] Lyutenitsa is a vegetable chutney generally made from roasted and pureed tomato, pepper, eggplant, onion, and various herbs.

[14] I further argue this claim in my dissertation (Craycraft, Sarah. Reinventing the Village: Generations, Heritage, and Revitalization in Contemporary Bulgaria. PhD Dissertation, Ohio State University, 2022)

[15] Donna Buchanan, for example, points to the three paths that “traditional practice” can take in contemporary Bulgarian folk music. (Buchanan, Donna A. “(Post?)National Portraits from the Postsocialist Soundstage: Three Bulgarian Folkloric Productions of the 2000s.” Beyond Mosque, Church, and State: Alternative Narratives of the Nation in the Balkans, edited by Theodora Dragostinova and Yana Hashamova. New York: Central European University Press, 2016) Joseph Feinberg arrives at similar conclusions as my own in his ethnographic study of folk dance revival in post-communist Slovakia (Feinberg, Joseph A. The Paradox of Authenticity: Folklore Performance in Post-Communist Slovakia. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2018). Lee Bidgood (Czech Bluegrass: Notes from the Heart of Europe. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017) and Carol Silverman (Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) offer nuanced looks at hybrid musics and transnational approaches to traditional forms in East and Central Europe.