This article is to be read in tandem with viewing the films, Ticket to Paradise (2022) and Eat, Pray, Love (2010).

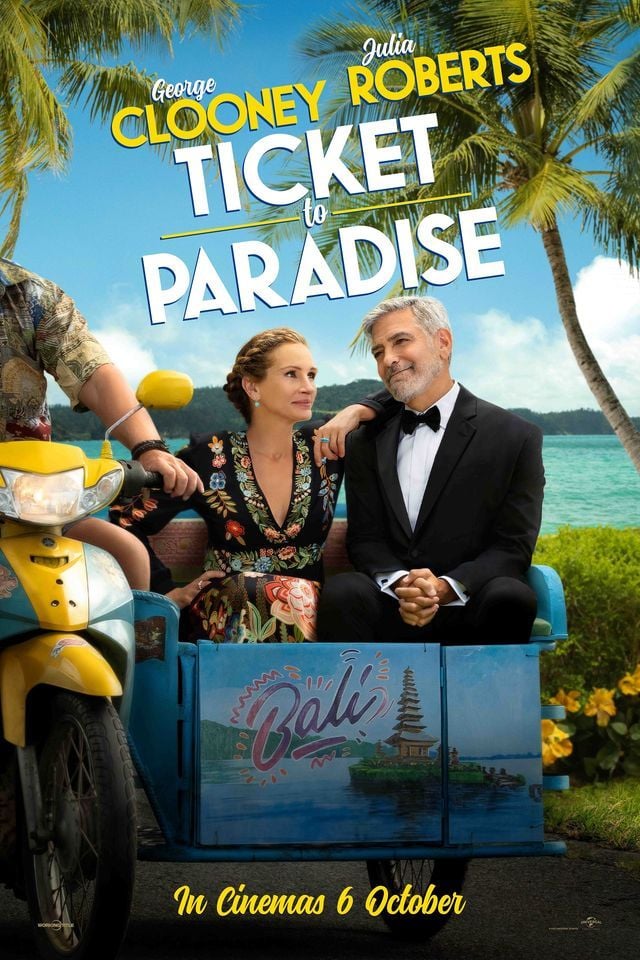

This article critiques the recently released romantic comedy, Ticket to Paradise (2022), and how it perpetuates the exoticist lens of Balinese-ness through discursive affordances of white privilege. Much of the film takes place in Bali, Indonesia, where the characters negotiate terms of engagement: between a Balinese boy and his American fiancée (who is finding herself after graduation); between the divorced parents of the American girl; between the parents of the American girl and her Balinese fiancé; between Balinese cosmological practices and American fragility. Just a little over a decade ago in 2010, Julia Roberts starred in the film adaptation of Eat, Pray, Love, based on Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2006 book by the same name, in which she plays a divorced woman traveling the world in search of herself by way of spiritual liberation. In 2022, Roberts returns in this film that passes on her new-age wiles, spiritual liberation, and white middle-aged privilege to the character of Lily (played by Kaitlyn Dever), who embodies the archetype of the young weary traveler swimming in a sea of post-college identity crisis. We look at this twelve-year time frame between films to argue that white privilege sustains globally, manifesting in different modalities while simultaneously reorienting the World’s view of local environments. In doing so, we pay close attention to an obvious cultural consultation effort that falls short of accuracy in depicting Balinese rituals, evident in the soundscape of the film. By taking postcolonial and sound studies approaches, we illuminate the intersections within popular media that contribute to potential stereotypes of Balinese-ness that then, ironically, contribute to the vitality of a global tourism industry. Additionally, we are also offering a critique of how this global tourism view and experience of Bali (and places that are represented similarly or equally problematically) shapes and reshapes our notions of rest, relaxation, coping, healing, etc. in our own “at-home” lives… It seems this tourism industry shapes affluent white people’s ideas of what they deserve, how they should identify vis-à-vis what is available to them, what resources they consume (i.e., nearly everything money can buy), and what aesthetic(s) they identify with, etc. Neocoloniality at its finest.

Bali has long been painted as an island utopia by national and global institutions through historic representations and popular media (conjuring images of paradise to attract the foreign bodies that the tourism industry covets), and this worldview is affirmed by social experiences had by diverse cosmopolitans on the ground. The methodologies taken in this article mimic ethnographic tenets, supplemented by approaches in critical inquiry. The article’s critiques are divided into three subsections: 1) “Utopias and Paradise in Film” contextualizes tropes of cultural tourism and how Southeast Asia, more broadly, is represented in film and through sound; 2) “Ceremonial Soundscapes and Linguistic Pitfalls” discusses Balinese cosmological sounds and the importance of rhythmic cadence in representing accurate interactions of socialization; 3) “Sociocultural Pain and Cultural Consultations” provides critiques on the importance of cultural accuracy in artistic work and proposes a working definition of “sociocultural pain” — a concept feathered with white privilege, spiritual liberation, and social escapism. Paying attention to these facets in films such as Ticket to Paradise and Eat, Pray, Love, we recognize the disturbingly prevalent worldviews and mindsets in many artforms that are diligent in shaping industries of cultural tourism. Works such as these demarcate power imbalances in global economies that are contingent on local peoples sustaining a life of servitude (see Indonesia’s colonialist Baliseering policy, instituted in the 1920s, that aimed to maintain and reproduce Orientalist ideas and images desired by the West).

This article comes from two authors who have lifelong and longtime relationships with Bali and its cultural formations. Our positionalities reflect different worldviews — that of a male Indonesian artist-scholar who grew up between the United States and Indonesia, and that of a white American female scholar whose work in Bali spans two and a half decades. Our reflections here are both personal and situated in prior academic works, and they function as continuous service to a global Balinese community. As these are both autoethnographic reflections of Balinese culture and reflections of our positionalities within a larger historical frame of cultural representation, we hope that they provide a path to enjoy the contrary depictions of popular culture while also advocating for a reformation of artistic contribution.

Utopias and paradise in film

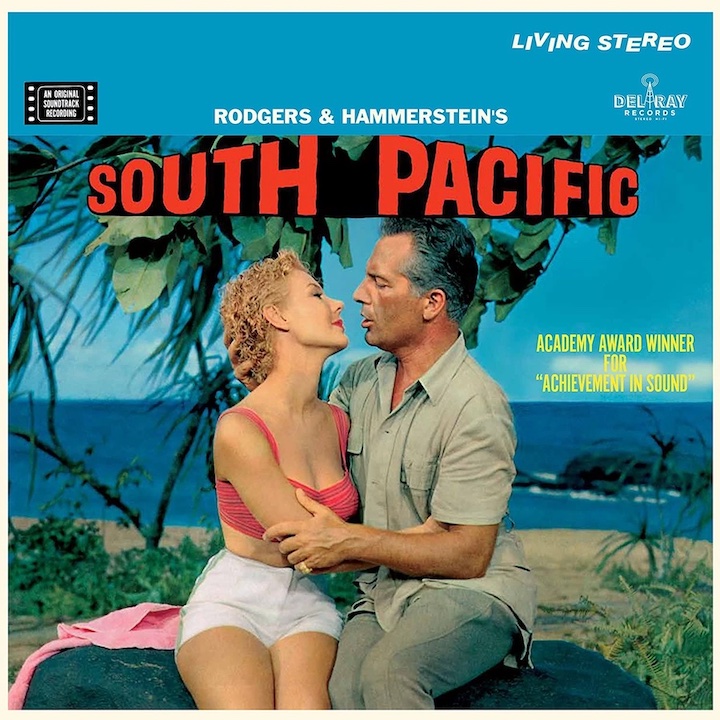

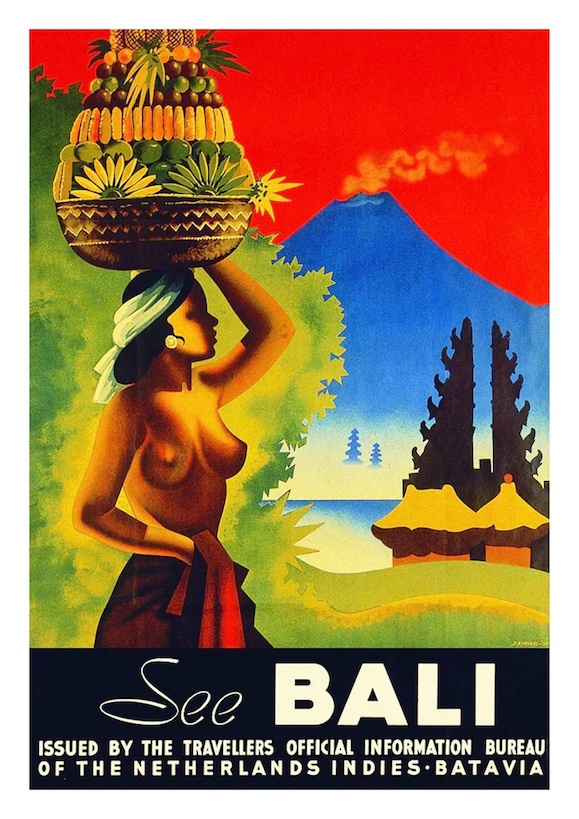

Balinese tourism has been constructed around the idea of difference, be it cultural, religious, or geographic. An image of paradise was created and fostered through early touristic advertisements, marketing, imagery, and ideas that circulated about the island (via cultural idioms, returning visitors, and popular culture). Western conceptions of Bali focused on exoticism and Orientalist ideals, from the 1930s New York City nightclub “The Sins of Bali”[1] to Rogers and Hammerstein’s fictitious “special island” in 1958’s South Pacific, in the song “Bali Hai.”

In her 1933 travel memoir, Bali: Enchanted Isle, Helen Eva Yates describes Bali as a “little paradise where men wear flowers in their hair, and strange gamelan bells ring at night; a paradise where people live happily without money, without clothes, and without enmity; a paradise where you can buy a little thatched bale (house) for a song and live easily on fruit and sunshine.”[2] This fictional “paradise” — one perpetuated by colonizers via slogans that idealized Bali as “The Garden of Eden,” “The Island of Love,” and “The Island of Bare-Breasted Women” — pervaded Western thought in the early twentieth century.

Eat, Pray, Love and Ticket to Paradise represent a continuum of Balinese cultural exploitation and white saviorism. While Gilbert’s New York Times best-selling travel memoir was praised and despised (for its self-absorbed priv-lit identity), the book and its film adaptation also inspired a generation of women to find themselves in Bali, where they, too, could seek out the spiritual enlightenment of the (now deceased) legendary “yoda-like” Balian (spiritual healer), Ketut Liyer. Eat, Pray, Love recounts Gilbert’s year spent living and learning in Italy, India, and Indonesia. In the film, Roberts (as Gilbert) wants to “marvel” at something — she wants to escape the life she’s living and find something more (she does, in the form of Javier Bardem’s Brazilian character, Felipe). Together, the film and book foster a sense of wanderlust, travel porn at its best.

A decade later, Ticket to Paradise represents the same sort of escapism. Director Ol Parker chose Bali “because it seemed like the furthest thing possible from the realities of the pandemic and English weather.” The film centers on the broken relationship of Georgia (played by Roberts) and David (George Clooney), the estranged parents of daughter Lily (Dever). Lily’s post-graduation trip to Bali with her friend Wren (Billie Lourd) is punctuated by a run-in with Balinese local Gede (French-Indonesian actor Maxime Bouttier), the wealthiest seaweed farmer around. Shortly after, Lily informs her parents that she and Gede will be married, and her parents travel to idyllic Bali (filmed in Australia due to the pandemic) to save their daughter from her decisions by launching their “Trojan horse sort of thing,” a plan to thwart their wedding.

Toward the beginning of Ticket to Paradise, a montage of social media postings plays, featuring stereotypical hashtags (i.e., #offtoparadise, #youdeservethis) that promise a quick fix no different from the jittery addiction of a Starbucks pumpkin spice latte. After all, what is paradise if not a carbon copy of every resort and food chain that exists to cater to docile relaxation? In fact, the cinematography of Eat, Pray, Love pushes food porn and a visual aesthetic of ethereality or dream states, centering socially sanctioned and commercially encouraged ways of relaxing. Bali is wrapped up in this larger cultural predicament in a very mainstream way with films like Eat, Pray, Love and Ticket to Paradise. And this problem is exemplified by the juxtaposition of Balinese peoples partaking in daily ceremony and frequent arts festivalization against foreign travelers embodying the partying culture of tourist beaches like Canggu, Kuta, and Uluwatu.

There is an emphasis on relaxation, but only as a succession to Instagram-filtered multi-sensorial bodily exhaustion. Not to mention, the presence of alcohol (which finds itself seeping into the pores of relaxation culture) acts as an elixir of escapism, leading to moments of poor judgment, the aftermaths of which reveal epiphanies enlightened on the stoops of imposing white ontologies. For instance, just as Clooney’s and Roberts’ characters partake in a hybrid game of beer pong — cups filled with Balinese moonshine called arak — Ticket to Paradise’s narrative takes a liminal pause to present a moment of potential empathy for cultural cohesion, only to be overtaken by another instance of privileged dominance over local ways of living. Even when drinking Balinese liquor, non-Balinese are better at living. Maybe the film didn’t intend to make this point, but it’s volatile nonetheless. The subsequent scene finds our two characters waking up in the same bed, questioning if they engaged in sexual intercourse (which has the Indonesian government concerned), which would reveal some sort of deep-seated desire for romantic reconciliation. Although alcohol truly is an agent within social gatherings in many cultures around the world, our critique here has to do with its aid in escaping cultural problems rather than resolving them. In true comedic fashion, both Clooney’s and Roberts’ characters find themselves using alcohol to maintain cultural distance, resulting in an elitist, unidirectional privilege contingent upon an unfair monetary exchange rate. Film, tourism, and sustained ideas about utopic islands represented across popular culture are active in channeling the tourist gaze here, a gaze centered on specific people, places, and sights that highlight exotic and idyllic ideas about Balinese culture.

Ceremonial soundscapes and linguistic pitfalls

The soundscapes of Eat, Pray, Love and Ticket to Paradise share common threads, indexing political agendas to promote liberation over social struggle. The sound designers often mask Balinese musics (such as gamelan) by relegating their performance to satisfying a visual desire (showing gamelan musicians, but not hearing them) and overlaying them with popular EDM or top-40s music, as a way to solidify a prescribed version of globally sanctioned spirituality. The sonicity of ceremony in these films is on par with global affirmations of representation in popular media, especially as pertains to which kinds of music have dominated cross-cultural sharings. In Eat, Pray, Love, Julia Roberts’ character goes to Italy where the soundtrack is Italian music; she goes to India where the soundtrack is Indian music; but when she goes to Bali, the soundtrack is Brazilian (symbolic of her love interest, Bardem). Similarly, in Ticket to Paradise, the soundtrack indexes some form of stereotypical “island” music: handpans, steel pans, slide guitar, and ukulele, with ascending melodies of stringed instruments (as heard in Hawaiian soundscapes, the long-sounding standard of utopia). Even in beach party scenes, a Balinese baleganjur ensemble (Balinese processional music) is shown but not heard, acting only as a visual marker of Balinese-ness; instead, the sound heard is a DJ spinning electronic music (reminiscent of the many beach parties and clubs that cater to tourists across the island today). Other elements sounding out paradise are filtered through homogenous sonic aesthetics, such as major pentatonic scales played legato in the strings and “island percussion,” all fixed to a western tempered tuning system and catered to indulge the whimsy of white reconciliation. Overshadowing local sound sources promotes the cosmopolitanism of expatriate communities, which feeds the fuel for Bali’s utopic popularity.

As for sounding language, although mispronunciation is common in media depicting cultural negotiations — and let’s face it, highly unavoidable in the midst of cultural exploration — it is not our primary point of interest here in considering the pitfalls and power dynamics of cultural consultations. Rather, we are interested in how representation is enacted in attempting accurate moments of socialization. For this reason, the nuances of Balinese rhythmic language cadences and choices of sound design become central to the elevation of important voices in the film. But implied at its margins are ontological frames that index the subtext of cultural power dynamics. Too often are culturally relevant monologues by Balinese characters (i.e., the welcoming of guests or introductory explanations of ceremonial rituals) overshadowed by the English-speaking, plot-thwarting schemers (Roberts and Clooney). By nature of the script and direction, sound designers decrease the volume of Balinese speakers to make Roberts’ and Clooney’s agenda to ruin their daughter’s marriage the focus of the scene. Although this may seem trivial, it illuminates the dismissal of cultural (and cosmological) importance for foreign cultural preference. The fact that so little dialogue between Balinese characters without white characters on screen happens at all, is concerning (and not dissimilar from gauging movies based on the Bechdel Test) — especially considering that in the plot of the film, the Balinese parents’ son is also about to marry a foreigner he has just met. Apparently, the American parents can be concerned, but the Balinese family (in the exact situation on the other side) need not be. Even as we watch scenes of the wedding ceremony, its keramaian (sonic boisterousness; comfortable noise) is subdued. As the pedanda (Balinese Hindu priest) enacts his incantations, the soundscape, which in real life is typically loud and vibrant, is compressed and quiet.

These tactics are no different than those in Eat, Pray, Love, except that when Julia Roberts’ character enters the Indian ashram for the first time, the audience hears an exciting and loud sonicscape of Hare Krishna — a more widely accepted Hinduism in white new-age cosmology. As we think about the presumed subservient roles Balinese people have in the frame of tourism, these sonic repressions are the reasons that power dynamics seldom shift in favor of local peoples. Tourists become far too ocular-centric in experiencing cultural differences, and are quick to dismiss the wonderful sonic elements that are prevalent in social interactions of this nature.

Inserted throughout the film are short exchanges in which characters exhibit qualms about Balinese cultural etiquette, and subsequently, demarcate Balinese ethics from their own. In Ticket to Paradise, quick lessons provided on what NOT to do — touch peoples’ heads, eat with one’s right hand, wear shoes in indoor spaces — are easy enough to remember for the moment but do not prompt further social inquiry, resulting in dismissal of cultural importance and relegating the act to: “of course people do things differently in other places.” And beyond those basic lessons, other ideas about culturally appropriate behavior (for example, the Americans are never dressed appropriately) are subsumed by the film’s reverence for white privilege. In Ticket to Paradise when the fathers of the betrothed meet for the first time, the Balinese father (Wayan, played by Agung Pindha, cultural consultant to the film and one of the few Balinese actors present) plays a joke on Clooney’s character by brandishing a large knife and saying, “And now we must cut our arms to be bound by blood.” The American dad is so frightened by this assumed barbaric custom, and his alarm that it still exists proves the endurance of Orientalist mindsets. The Balinese father then laughs off his prank, saying, “You should have seen your face.” Surely, the writers added this in as a way to cut the tension of exoticism, but the joke is a dull knife, making any good intention easy to dismiss.

Sociocultural pain and cultural consultations

The idea of pain as sociocultural phenomena becomes particularly salient in the context of ceremonial rites of passage. In Ticket to Paradise, this pain manifests in Dever’s transition between graduating college and entering “the real world,” as well as in various Balinese rites of passage rituals that appear in the film, such as, mesangih, or tooth filing ceremony. Here, we define sociocultural pain as suffering or discomfort that is an identifiable component of ethnoaesthetics: pain that exists as a marker of social and cultural boundaries. Be it emotional or physical in nature, this pain is agreed upon in codified cultural discourse.

Throughout the film, the remedies for white pain are ostensibly justified through the employment of larger narratives of merit and deservedness. In Ticket to Paradise, these pains become plot points that create contention: competition between two divorced parents (i.e., who is the better parent?); daughter letting down parents if her life path is skewed and altered; daughter being out of balance and trying to find it in Bali; four years of self-beating in college; the empathy of children’s pain as being parental pain. Dever’s character justifies her response to pain with a simple line at the end of the film, “I belong here,” referring to her perceived deserved positionality in Bali. Interestingly, in these narratives of white entitlement, the pain of the self is remedied through exposure to less privileged persons. It is far too convenient to get a visa on arrival and overextend your stay in search of spiritual utopia, which is what makes scenes in Ticket to Paradise — like when Lily is asked why she is getting married and responds with “…because Bali is so beautiful” — truly abhorrent. As we see, the white privileged response to emerging pain is mitigated not through overcoming struggle; it is remedied by perpetuating a “go where you want to go, take what you want to take” attitude.

On the other hand, the pain of Balinese people depicted in the film is constantly sidelined and remedied by being cast as a local problem, rather than a glocal one like white pain. The young cousin of the soon-to-be wed Balinese boy, Gede, loses the wedding ring — which is actually stolen by Roberts’ character in an effort to stop the wedding — and when the whole day of ceremony is canceled, they just brush the incident off and postpone the wedding. In real Balinese ceremonies, this would cause huge physical and cosmological pain and labor.

Depictions of physical pain are also framed through comparative culture and extend beyond the threshold of slapstick comedy to ensure the narrative’s exoticist tinge, effectively also acting as a remedy for white pain. In Bali, tooth filing ceremonies are life cycle rituals that are performative in nature: your social status changes once the ritual is finished. It is a ceremony that is intimate for you and your community, structured to elevate humanistic qualities above animalistic dispositions. As the priest files your teeth down, it is an odd sensation indeed, but it does not typically involve as much scrutiny and discomfort as depicted in Ticket to Paradise, with the audible pain and squirmish reactions. The scene is punctuated with the words, “This is worse than Jewish circumcision,” and the narrative finds yet another way to make it relatable to (and beneficial for) the hegemony. But what is potent in the film’s ingredients for reinforcing exoticness is the use of Balinese cultural idioms to alleviate any social discomfort. The writers use desa, kala, patra (the Balinese concept that says the success of ceremony requires the correct place, time, and circumstance) to bypass any potential challenges the marrying characters might face. This concept is both part of, and wielded as, an attraction that Bali affords and is commonly embodied by expats and travelers. It is an element of Balinese culture that can be easily digested and immediately applied to the wounds of sociocultural pain.

The mishaps of cultural consultation in these films are not so easily reduced to naivety or ignorance concerning Balinese culture, but they bypass any potential for dialectical relationships to be made with diverse communities. The consultants not only act in the film, but have allowed for film industries to capitalize on the commodification of culture for a moment of fame and a taste of white privilege.

Bringing together representations of pain with the linguistic and sonic pitfalls we’ve examined, it’s evident that these priorities of cultural depictions are only intended for the dominating ocular-centrism of popular media and its consumers. There is a difference between the ethnoaesthetics of mythology — that are models of social relationships for Balinese people — and the attempted comedy to provide white people an understanding of Balinese lore. For one last example, a scene in Ticket to Paradise shows a Balinese character joking that Roberts’ character has the beauty of Sanghyang Jaran (a very sacred horse spirit associated with trance rituals). The writers are trying to find a way to integrate Balinese folklore to say that Julia Roberts has a horse-face. Is this body shaming packaged as exoticist imposition? It’s not as deep as that; it’s just a moment of batu melebleb (boiling confusion). Jokes, such as this one, make no sense once translated and are disorienting, thus becoming problematic because the weight of the joke sits on contextual cultural semantics that are not explored — representative of the film’s entire inadequate approach to cultural consultation. It is not only painful to watch, but painful to hear.

Conclusion

Whether viewers of these movies are attempting to live vicariously through the affordances of romantic comedies or at the very least, finding models to accrue some inkling of self-respect by way of global social capital, these platforms affirm power dynamics that maintain local servitude within homogenizing world views. We’re prepared to admit that Ticket to Paradise is entertaining and comedic, precisely both what Clooney and Roberts have signed up for (they are understandably witty in their characterization of naivety and their particular brand of beauty is humanized when wrapped in an aura of slap-stick humor) and the effect the movie is supposed to have as a standard example of the romantic comedy genre. Unfortunately, within this standardization, these films co-opt our cultural expectations to be satisfied without a critical inquiry toward and through that satisfaction. A film like this ends up doing a good deal of harm to Balinese people and it perpetuates a pattern of exoticism against the notion, reality, and worldview of Balinese-ness. Our critiques stem from our relationships with Balinese communities and families, not from a two-hour pseudo-travel film that might offer viewers a way of being in another country (that plays directly into idealized touristic imaginings). Imagined utopias, ceremonial soundscapes, and sociocultural pain are all wrapped up in a web of surface-level accessibility that bypasses any of the sublime nuances of difference, catering to white epistemologies and ontologies. All of these elements of mainstream creativity push cultural and conceptual harm, which manifests in tangible social ills. And this surface-level interaction even contributes to Balinese assumptions of how to interact with foreign travelers. This kind of harm is constantly reincarnated and difficult to depart from, allowing for a super-imposition of white values onto the overgrown expatriate areas of Bali. The relationship that privilege creates in global travel is supposed to expose corrupt power differentials toward a more nuanced understanding of cultural difference. Instead, it masks the layers of social contention by carving out only that which is readily accessible. If the purpose of “utopia” is only the “you,” the term emerges as objectively condescending. Is the island of one-thousand temples only available for philosophical entertainment? If white privilege belongs in Bali, then where are the Balinese privileged?[3]

[1] Adrian Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created (Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1989): 120.

[2] Helen Eva Yates, Bali: Enchanted Isle (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1933): 19.

[3] On February 7, 2023, vlogger Nuseir Yassin (popularly known as Nas Daily) posted a video pointing to Bali as “the whitest village in all of Asia” (sic). Quickly critiqued for its glorification of gentrification and white privilege, the video spawned angry memes and hashtags like #blamefuckingjuliaroberts and #eatprayleave.