All art is propaganda; on the other hand, not all propaganda is art.

George Orwell

Introduction

As a student of narrative, I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of propaganda. After all, when it comes to art that has changed the larger conversation, propagandistic techniques have been historically incredibly effective. So it behooves me as an artist to answer for myself the following questions. Where falls the line between caricaturizing “base propaganda” and more truthfully complete “artful propaganda”? When does unnuanced “base propaganda” lead to good art? And how does an artist decide which form of propaganda will be most effective at any given time in history?

Propaganda itself is defined as “the dissemination of information — facts, arguments, rumors, half-truths, or lies — to influence public opinion.” I must admit that as a fiction writer, this is exactly what I seek to do with much, if not all, of my work. So, in accordance with Orwell’s quote above, it benefits an artist to realize that all the art they create is some form of propaganda. I also recognize it’s impossible to define “base” and “artful” propaganda for every artist, but I have spent many years coming up with characteristics that help me, at least, distinguish between the two in my own writing.

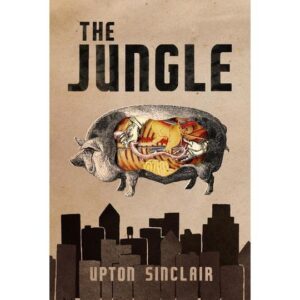

It also bears repeating that this does not mean that I seek to extinguish propaganda from my work (this would be a ridiculous neutering of the power of my own written word), nor do I believe that the techniques frequently derided in public discourse as elements of “bad propaganda” should always be forbidden to “good art” (who can argue about the good that Upton Sinclair’s 1906 propagandistic novel The Jungle had upon meat inspection standards and public health?). No, I simply desire to know when I am using propagandistic techniques, and for what reason. The following article lists some of my thoughts on the subject.

But first, a tale from the annals of American literature.

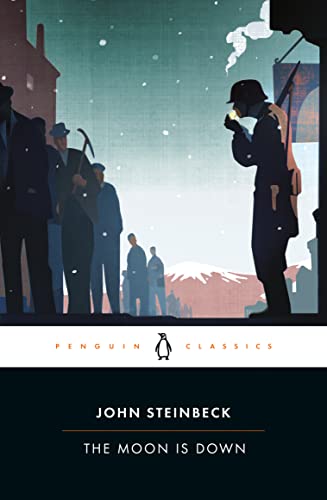

A case study in American history: John Steinbeck’s The Moon is Down

Summer 1940. The Nazis had engulfed much of Europe. John Steinbeck, by then already a world-famous writer, believed that U.S. involvement in the war was inevitable and worried about the quality of the propaganda being produced to persuade the common American. Wanting to contribute to the Allied cause, he met with President Roosevelt to speak his concerns. Consequently, Steinbeck was assigned to work for two organizations that were precursors to the CIA: the Office of Coordinator of Information (COI) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In these roles, after meeting with displaced citizens from recently occupied European countries, he decided to write his own fiction work of hopefully better propaganda.

He originally set it in a medium-sized American town, but after advice from government agents, reset it in an unnamed country that is an amalgam of Norway, Denmark, and France. Published in early March 1942, he named the short novel The Moon is Down after a quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. It was notable because it did not depict the Nazi stand-in invaders as heel-clicking, sieg-heil-screaming tyrants. Instead, these invading soldiers offered rationalizations and reluctance, missed their families, claimed their actions “civilized,” and desired acceptance. In spite of these villains’ more three-dimensional humanity, the town patriots, led by their mayor, still stand up against them. Though these invaders were not a caricatured evil, totalitarianism was still portrayed as unnatural and deserving of being fought against.

Soon after the book’s publication, the attack on Pearl Harbor happened. At a time when Americans were suddenly being encouraged to join the war in the simplest, most black-and-white, caricatured terms, many prominent reviewers savaged Steinbeck’s novel, accusing him of naïveté and softness. They claimed that Steinbeck’s propaganda, by featuring a more nuanced, three-dimensional portraiture of the invaders, would demoralize the victims of Nazism in occupied Europe. The controversy and discussion of which kind of propaganda is more effective — the harder-hitting rah-rah good vs. evil archetypes or Steinbeck’s fuzzier fable — raged for months in major newspapers and magazines.

In America, The Moon is Down is not remembered as one of Steinbeck’s best works. However, years after the war was over, information came to light about the book’s impact in war-torn Europe. The book had been distributed religiously and industriously under the very nose of the Gestapo throughout Norway, Denmark, Holland, and France. Civilian resistance fighters risked their lives to disseminate the story because it struck such a chord with the occupied. The Nazis banned it whenever they found it; in Italy, simply having a copy meant you could be put to death. Still, hundreds of thousands of clandestine editions were circulated in occupied Europe. It was hailed in Norway as “the epic of the Norwegian underground.” Its translations sold in bestseller numbers in Denmark and France. To those who actually had been directly and personally affected by the war, Steinbeck’s form of propaganda was considered far superior to anything depicting the Nazis as snarling, inhuman, unfeeling caricatures.

In 1946, Steinbeck traveled to Norway to receive King Haakon’s Liberty Cross medal. He was asked how, living so far away in America outside of Nazi occupation, he knew so well what it felt like to be a member of the resistance. He simply responded, “I put myself in your place and thought what I would do.”

(For further reading and resources about The Moon is Down, its conception, controversy, and impact, please see Stephanie Forster’s analysis or Donald V. Coers’ detailed retelling.)

My self-defined five differences between “base” and “artful” propaganda

When I use the terms “base propaganda” and “artful propaganda” throughout the rest of this article, I do so to delineate between what I would consider propaganda which embraces unnuanced and caricatured characters and that which provides more three-dimensional portraits. I understand that the terms are not clearly or cleanly divided (a single work may be unnuanced from one angle, and highly dimensional from another), nor should they be, but I believe it is the duty of an artist to consider the differences for themselves.

The following are the five signposts by which I delineate “base” and “artful” propaganda in the works that I create and enjoy.

#1. Base propaganda works in symbols; artful propaganda works in characters.

For me, the underlying essence of base propaganda is that the characters are subservient to what they represent (especially as an archetype or modality of good or evil); the essence of artful propaganda, on the other hand, is that the characters long to break past the archetypes that confine them. Therefore, this lesser propaganda relies more frequently on the use of symbols and shorthand audiovisual cues.

The famous Odessa steps slaughter sequence from the silent Soviet film Battleship Potemkin (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein, for example, uses lion statues to represent the Russian people, first sleeping, then awake, then angry. By not focusing on any individual character in this climactic sequence — after all, the ostensible protagonist Vakulinchuk is long dead by this point, removed from the narrative by the end of the second act of five, and never had any history or motivation beyond his identity as a revolutionist in the first place — the symbology of the movement becomes more important than the individual.

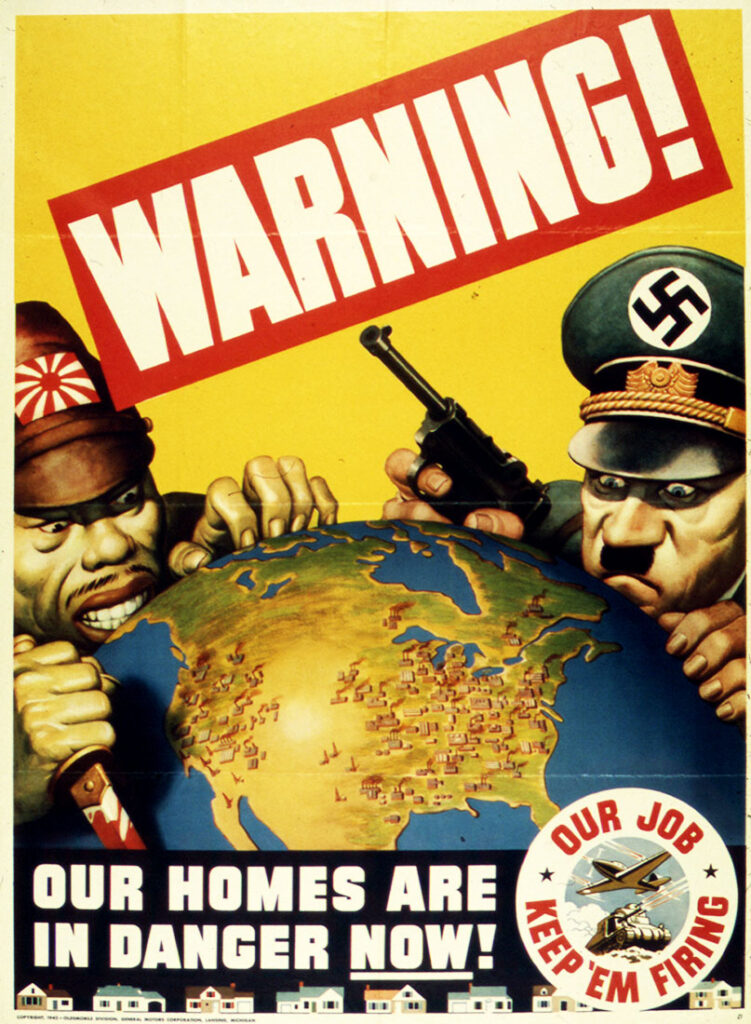

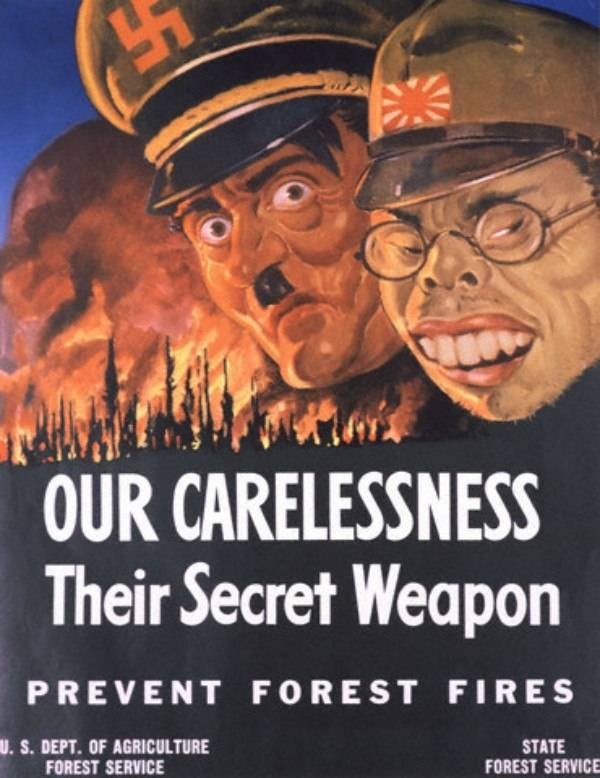

Even “characters” like Uncle Sam or Rosie the Riveter are single-minded, and seemingly joyful to become symbols of the larger movement, never showing human doubts or dimensionality. WWII posters reduce complex issues to simple reductive positionalities, and of course, enemies are depicted without nuance or compassion.

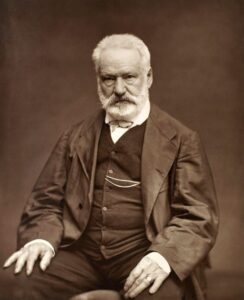

In more nuanced “artful” propaganda, on the other hand, it is harder to dismiss a character with only one archetypal identifier. In Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel Les Miserables, Jean Valjean spends the entire narrative breaking past the confines of the archetype of “criminal,” a description that his antagonist Inspector Javert believes is more than enough to define him. In fact, as in most of Hugo’s work, reductive archetypal classification is frequently rebuked. Equivalently, in Notre Dame de Paris (1831), Quasimodo is much more than the “hunchback” he is diminished to; Phoebus, the handsome soldier, is not the hero of the tale, as he is initially presumed to be based on look and station; and Dom Frollo, the Catholic priest, is not quite the spiritual light he is lauded to be. Hugo’s characters are not symbols; they commit actions that frequently break in the opposite direction of the archetypes of their time.

(Hegemonic institutions historically have little patience for nuance, preferring base propaganda that breaks in their favor. Hugo is an excellent example. Despite both of his major novels being treatises on human kindness toward the less fortunate and very devout towards the idea of a moral and just God, the Vatican placed both works on its Index Librorum Prohibitum, their list of books forbidden to the Catholic faithful. They remained there from publication until the ’50s.)

#2. Base propaganda deals in convenient omission and deliberate misinformation; artful propaganda, even when fiction, cannot.

This difference seems obvious, but there is a certain undeniable blunt-force effectiveness to disinformation. It is what Fox News did to America through politainment. And it works. Nuance does not frequently resound as well within the emotional caverns of contemporary zeitgeists. After September 11th, very few wanted to deal with the terrorists as “human,” as seen when Bill Maher was dismissed from his show Politically Incorrect for being unwilling to label the hijackers as “cowards.” And does anyone truly want a nuanced humanizing biography of Harvey Weinstein right now?

Conversely, Andrew Dominik’s Blonde (2023), released earlier this year to great controversy, reduces Marilyn Monroe to nothing other than the symbol of “victim.” Review after review criticizes the film for cutting past scenes of her acting, talent, and inner drive to focus on nothing but her exploitation. She is less character than tragic symbol. Dominik claimed in interviews that this made the film high art. Does it? Dominik’s argument seems to be that if, as Steinbeck believed, dealing with an oppressor with nuance is higher art, then the inverse is true as well: reducing the persecuted (normally treated with more nuance) to a one-dimensional symbol must also be higher art.

It’s a complicated argument, but I must respond with “no.” In my opinion, artful propaganda becomes such because of what it is willing to inconveniently include while still managing to make its points, while base propaganda earns its moniker through what it is eager to conveniently exclude to do the same. Therefore, for me, Blonde falls under the category of more artless propaganda.

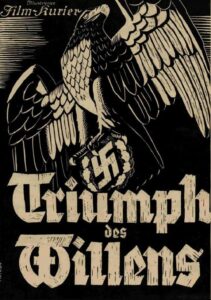

Triumph of the Will (1935), along with other Leni Riefenstahl Nazi works, is clearly base propaganda because of this same delineation. Yes, sadly, there is some truth in this landmark documentary film about Hitler’s 1934 Nuremberg rally: there were hundreds of thousands of German Nazis gathered here, these speeches were made, Hitler was lionized and saluted, and he did instill a patriotic fervor throughout his countrymen. But what makes it lesser propaganda is what it excludes: the maniacal and murderous cost of this patriotism.

#3. Base propaganda asks that others understand us; artful propaganda demands that we understand others.

John Steinbeck, when accepting King Haakon’s Liberty Cross medal, said it cleanly: he did not write The Moon is Down to reflect his own strong anti-Nazi feeling; he wrote it to understand the feelings of those who lived in occupied Europe. Therefore, in my opinion, base propaganda is self-expression; artful propaganda, on the other hand, is empathy.

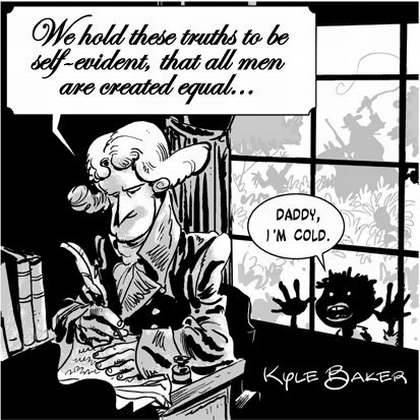

Once again, I must reiterate that I do not think all base propaganda is bad. Sometimes it is even necessary. Self-expression is not always bad; there is significant value in the underrepresented voice being finally allowed to express itself and its version of truth. Perhaps we are due for a biopic that shows Thomas Jefferson not as a three-dimensionally moral, conflicted figure, but as a simple villain: a selfish man of convenient values who slept with a woman he owned and decided that her struggle wasn’t worth the national argument in that moment. The skewering of a nation’s sacred symbols through base propaganda frequently predates a more nuanced conversation in the future. Without base propaganda, the conversation might never elevate itself to its better counterpart.

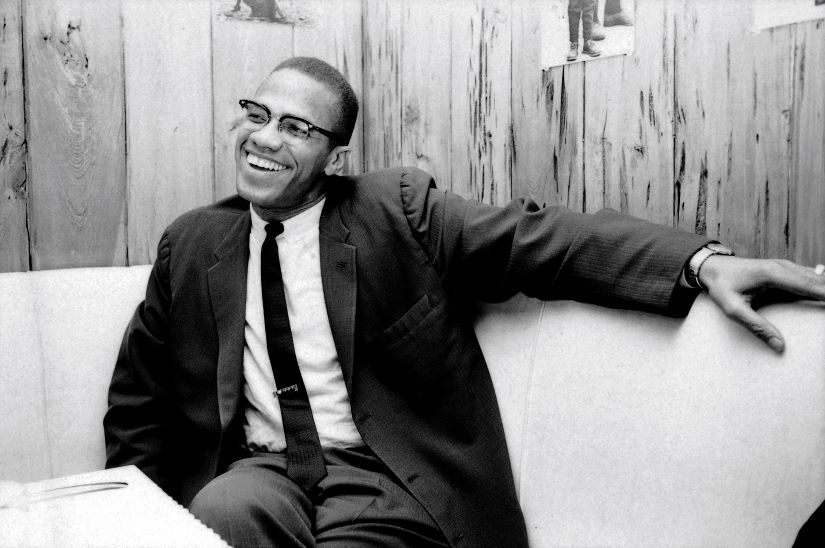

Malcolm X himself wrote in his 1964 Autobiography, “In the past, yes, I have made sweeping indictments of all white people. I will never be guilty of that again — as I know now that some white people are truly sincere, that some truly are capable of being brotherly toward a black man. The true Islam has shown me that a blanket indictment of all white people is as wrong as when whites made blanket indictments against blacks.” But a cynical side of me wonders whether anyone would ever have read this more equanimous statement had he not begun with the more strong-willed rhetoric.

Base propaganda has proven to be a great way to first get cultural attention; artful propaganda has proven to be a sublime way of following up on the captured attention to cement lasting change. Perhaps without Malcolm X, no one would have listened to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Perhaps without the more extreme voice, the moderate voice cannot operate with nuance. It’s a frightening thought, but not one without its merits.

#4. Base propaganda persuades issue outsiders; artful propaganda works on those most affected.

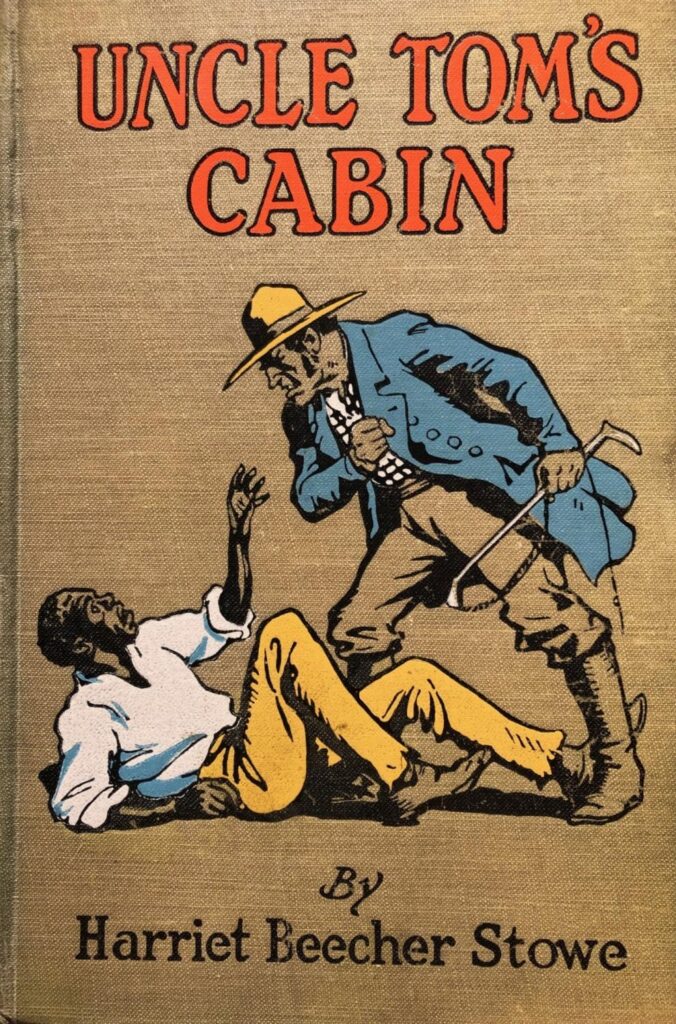

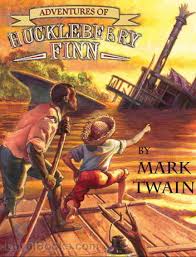

Two works that vastly affected how African-Americans and slavery were perceived in America are Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). I would posit that the former is more base propaganda while the latter is more an example of artful propaganda. Both were instrumental to changing attitudes, but in very different ways.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicts the horrible lives that slaves underwent, all under the lash of a mustache-twirling villain unsubtly named Snidely Whiplash. It was a wake-up call to those who did not live in the South, an exposé of inhuman cruelties. To Americans with no firsthand familiarity with slavery, the novel was a shot in the arm, and swelled abolitionist ranks. However, the same book was also derided by Southern whites, who dismissed the novel as factually incorrect because some slaveowners did not treat their slaves in such an egregious manner. Many Southern white slaveowners claimed not to recognize themselves in their novel counterparts, claiming the book cherry-picked the worst experiences to make a factually invalid case. (Maddeningly, the fact that every incident in the novel did happen to some slaves did not seem to be of enough merit to discredit the institution of slavery as a whole.) In fact, the book even gave rise to its own counterpropaganda, so-called anti-Tom literature, a series of proslavery works that passionately propagated the image of the “happy slave” and depicted instead cruel Northern attitudes to the working class, or what this literature frequently described as the “white slave.”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, on the other hand, is told from the point of view of a poor white boy who casually uses the N-word, then ends up slowly discovering the humanity of Jim, the runaway slave with whom he sails down the river. Over the course of the narrative, Huck learns that Jim is much more than the one-dimensional, lazy, lesser archetype he has been taught. This novel did work in the South as well as the North, having had the advantages of both two decades of hindsight and a refusal to demonize those who did not sooner see the truth.

I believe the artist’s responsibility, therefore, is to study where we are in the cultural conversation, and what it takes to move the needle toward change. And, as always, the artist’s responsibility is to know specifically your audience: do you intend to awaken issue outsiders to their blindness, please insiders who have been hurt by helping them have representation, or artfully persuade insiders on the opposite side of the debate? I believe base propaganda can serve the first two functions, but it can never achieve the third. However, while artful propaganda can achieve the third, its arguments are frequently not even heard without society having been exposed to the first two.

A more recent example of necessary (though perhaps base) propaganda might be Promising Young Woman (2020), the Carey Mulligan film about rape culture. Spoiler alert: it does bother me that there isn’t a single young man in the movie who isn’t, ultimately, a villain; young men are reduced to symbols of oppression more than characters. However, the exclusion of a young male ally is deliberate; such a character would certainly inconvenience the film’s messaging. However, I know that many women do feel this way about the world, that all men are potential assailants, or silent supporters of assailants, and that is necessary information with which to begin the conversation.

My favorite G.K. Chesterton quote is, “Art, like morality, consists of drawing the line somewhere.” In Promising Young Woman, the film’s director Emerald Fennell chose to draw the line here, between men and women, and from this lens, sure that’s unnuanced and perhaps even infuriating, but we cannot forget that nuance comes most effectively only after a critical foundational layer of the conversation has been laid. Perhaps in time, the conversation of rape culture can advance, and we will finally be able to ask the question, where shall the line be better drawn? But is society there yet on this issue? Or do we still need base propaganda to grab the zeitgeist by the throat and demand attention?

#5. Base propaganda works best in the cultural moment; artful propaganda can work centuries later.

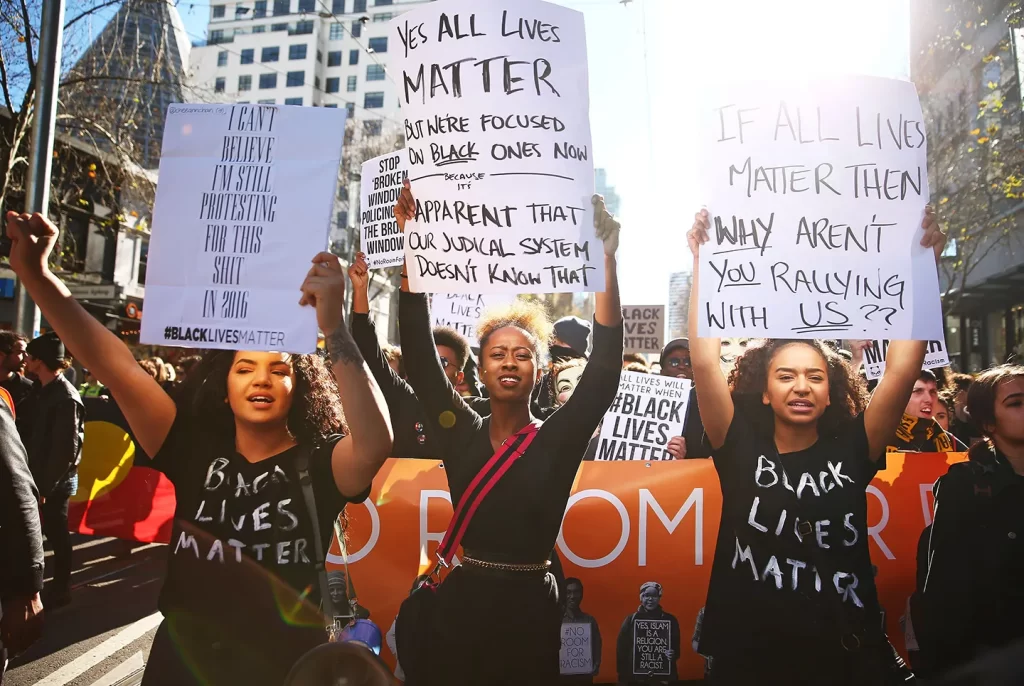

Over the past decades, politics has had me increasingly despairing. It’s frustrating to me that it is 2023, and we’re still debating issues based on the most rudimentary religious, racial, nationalistic, and wealth divides. We live in a time that prizes self-expression over conversation, a period tailor-made for propaganda, all soundbites and reductive symbologies. Yes, Black Lives Matter is a “simplistic” statement — but the fact that it needs to be said at all, much less endure being “debated” and countered by the asinine statement “All Lives Matter” makes any chance of nuanced conversation seem impossible. It is devastating that America is still at a Black Lives Matter level of discourse, that this exasperatingly obvious and innocuous slogan is still met with resistance and pushback. When are we going to be able to move past this to any level of nuance, bulwarked by actual psychological change and readiness within the populace? For a writer like myself, who would love to be dealing more with nuances of racial diversity rather than with the obvious argument that black people deserve not to be killed, it is a frustrating time. I recognize that this might seem similar to All Lives Matter talking points, but there is a difference between wanting the conversation to advance without systemic change and wanting the conversation to advance after stipulating the obvious and enacting systemic change. We must never forget that between Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn lay the Emancipation Proclamation, and without it, the “white man archetype” of Snidely Whiplash could never have progressed to the more innocently oblivious Huck. An artist’s primary duty, I believe, is to be connected to the world’s energies, to meet the audience where they live — and not to ignore the realities of our audience.

Therefore, I believe that as artists of today, we cannot so easily dismiss the techniques of baser propaganda. Without them, our work might never get attention within the too-content-crowded artistic sphere, especially when we lack the marketing budgets of the major corporations who will always be heard above the din (and, to be honest, prefer the easy answers of more artless propaganda, anyway). However, once we have the necessary level of audience attention, it is also our duty to elevate the discourse as we can, step by step, advancing the conversation and enacting change with each piece. As quixotic as it may sound, I do believe that good artists are the last line of defense within our current infantile political climate, with education brutally crippled. It is an artist’s duty to do both — to balance the techniques of base and artful propaganda and to know when to implement each even within a single work. Perhaps the work’s pitch sounds like propaganda while the content is surprisingly nuanced. Perhaps we begin from a simpler place and allow the characters to grow within the story. Or, perhaps like Malcolm X, we increasingly strive to move toward nuance in our own hearts.

We must also always be careful, because there are those who will always claim now is not the time for nuance, whether compelled by maintenance of the status quo, a fear of change, stasis through trauma, or stubborn prioritization of “larger purpose.” But the arts demand the courage to trust one’s own perception of the world, not to react or to follow in the footsteps of what others are saying/doing, but to stand behind one’s own instincts and appraisal of the zeitgeist about when to take the risk of engaging with a concept at the next level of discourse.

In Shakespeare’s MacBeth, Fleance says, “The moon is down; I have not heard the clock,” referencing a clock that always strikes at midnight but that, on this very dark night, has not yet sounded. Yet Fleance believes it is past midnight, and wants to follow his own perception. This is the passage from which Steinbeck found his title and we, as artists, must find our calling. There is no outside clock that will sound the moment the audience is ready for elevated discourse; all we have is our own sense of time.

Base propaganda, when the dust has faded and the scores are settled and the world has genuinely moved onto a higher level of conversation, will always have the patronizing and dated patina of a World War II poster. While base propaganda may be immeasurably impactful (and even necessary) in the immediate, artful propaganda survives in the long term, the characters taking on a timeless quality. However, that timeliness is not earned easily.

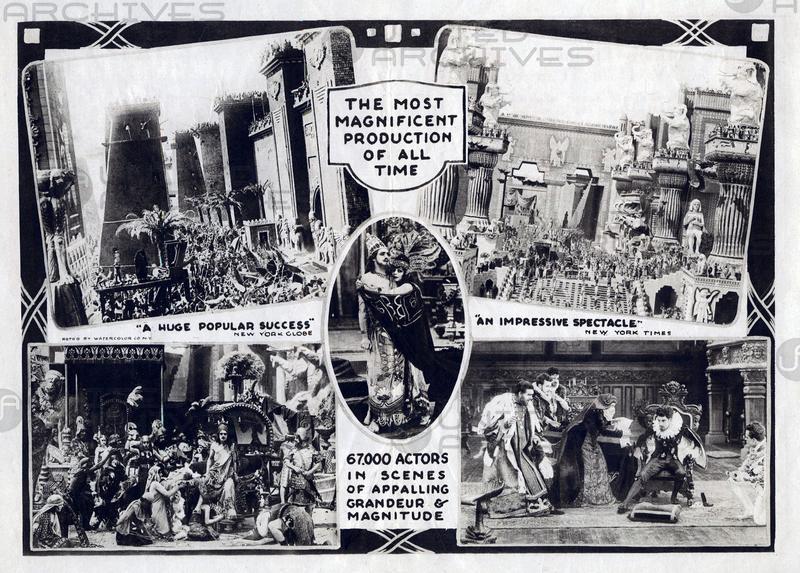

Shakespeare’s Othello survives because the tragedy of the titular character’s actions is not defined solely by his blackness, his goodness or his evil, but by a willfully provoked and nurtured human jealousy. On the other hand, D.W. Griffith’s horribly racist epic The Birth of a Nation (1915), lionizing the birth of the KKK, reducing characters to symbols and archetypes to make Griffith’s propaganda points — despite the many artistic and technological achievements the film pioneered — was always fated to be nothing but a cultural artifact, popular and explosive in the short-term but faded over time. (If Nazi Germany had Leni Riefenstahl, then America has D.W. Griffith, a genius artistic stylist whose only goal was propaganda and self-expression. See also Intolerance, released in 1916 as Griffith’s follow-up film, in which he was laughably trying to make over and over again the point of his own persecution, and people’s intolerance toward him.) Similarly, I can only dream of a future where the one-dimensional nefarious young men of Promising Young Woman or the statement Black Lives Matter are considered too simplistic to be adequate, for artists, thinkers, citizens, and discourse will all have holistically, systematically, truthfully, and empathetically moved the needle of discourse.

Conclusion

My ultimate point is this: as artists, it is our responsibility to differentiate for ourselves the frequently intertwined techniques of base and artful propaganda, to be clear about our purpose, audience, and ethical goals, and to carry the conversation forward with the actionable discourse that we have introduced. In our modern world, when lesser propaganda and polemic speak loudly and come backed by endless big-business dollars, it is more difficult than ever for nuanced, ethical, artful persuasion to be heard above the noise. As Orwell famously stated, not all propaganda is art, either; largely, contemporary advertising and PR (and increasingly, the news) are not art simply because they use artistic tools, forms, techniques, processes, and methodologies; no, they are only lesser propaganda, so much of which inundates us every single day. It is why so many artists are forced to resort to the use of the simplest symbols and narratives, one-dimensional archetypes, or the shortest soundbite, to join the propaganda or counterpropaganda machine, in order to even be heard. It is why our conversations have regressed over the last decade, why we are again arguing for social progress we had thought transcended.

A final thought: the trick to artful propaganda is that the nuance must not lead to inaction or moderation; Steinbeck does not stand any less against totalitarianism than a reductive WWII poster. No, artful propaganda simply better understands that change is not easy, that there are no simple villains, no perfect solutions, and no blameless heroes — and yet stands for progress regardless. Nuance does not have to lead to tolerance of evil, stasis, or inaction; we must understand that while base propaganda may be an effective demolition, artful propaganda must be the construction of something different and more durable; it is the only thing that keeps the old systems from being rebuilt exactly as they were all over again.

Still, somehow, we must find a way to make the noise and have the nuance. It’s a struggle I face with every single thing I write, and it is an insurmountable one if we, as artists, do not define clearly for ourselves the necessity for and impact of propagandistic techniques. As audiences, too, we need to understand when the nuanced conversation is being had versus when it is being avoided, in order to inure ourselves against the infantilization of our dialogue, to keep systemic institutions from forcing a society in which we are fated endlessly to deal with caricatures, without the possibility of genuine progress, the greatest artists and thinkers of our times held at bay by the Sisyphean task of reinventing wheels endlessly mired in the mud.

After all, why make movies if we do not add to what was said before? Why write if we only repeat the words of others? Why tell stories if our characters can never transcend the archetypes by which we find ourselves confined? And why play music if all we express are our own stories, oblivious or apathetic to others? Why make art at all, if we do not build towards something new, connected, and lasting?