There are many reasons to study history, especially if we study it in a holistic, non-linear manner: critical thinking; consideration for alternate perspectives; the evolution of our ideas, ideals, and idols as new information is introduced; and perhaps most importantly, empathy and respect for those whose voices and stories are overlooked. This applies (with added layers, of course) when studying the history of a creative discipline. Whether you’re a musician, dancer, educator, listener, or any combination of these, it’s useful to connect your reasons for studying the history of an art form with the reasons you became interested in that art in the first place; this connection will guide you to a depth of understanding and appreciation that is very tangible but difficult to describe.

What if we all engaged with jazz history, for instance, not just as a matter of course, but out of fascination, passion, respect, curiosity, richness, wisdom, love, whimsy, creativity, inspiration, depth, authenticity, and joy? What if the goal was to understand, to the extent that anyone can, what inspired those who inspire us? To hear the stories of those who lived through earlier evolutions of the art form — to know what was important to them? To learn their struggles and triumphs? To pay homage to their memories by listening and allowing the richness of their experiences and music to add to the richness of our own? To immerse ourselves in the most diverse “soundscape” possible so we have all the tools at our disposal to find our own unique voices? What if that was the motivation instead of ticking a box for a curriculum requirement?

To that end, the status quo of jazz historiography — especially in traditional academic settings — is in need of a massive overhaul, but that is a rabbit hole for another day. The complexity and ineffability of this genre and its history are due, in no small part, to the incredibly rich and convoluted web of influences and occurrences that lead to the particular coalescence we hear on now-revered recordings. Jazz history is a web with more strands than one could ever count. Perhaps the change we need can be nudged in the right direction by following one thread at a time, taking the intrinsic value of the exploration, rather than a sense of obligation, as our motivation.

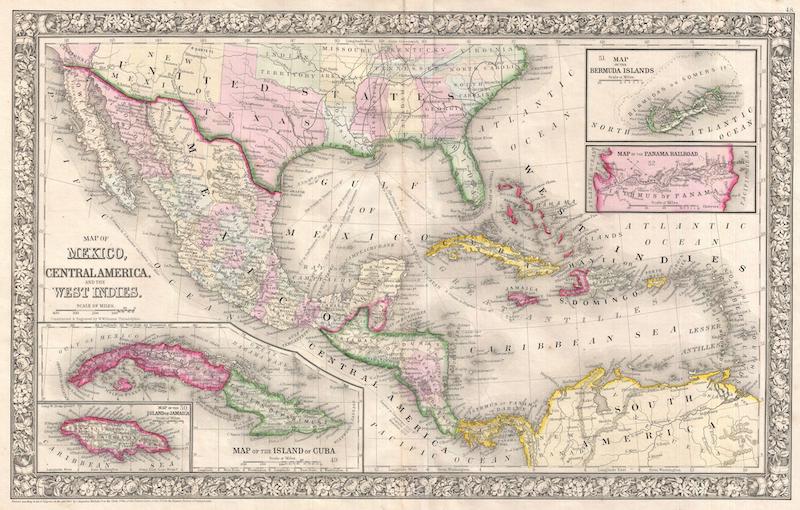

One particularly fascinating thread often under-explored in the conversation on jazz history is the musical relationship between New Orleans and the Caribbean, especially Cuba. The development of danzón, considered Cuba’s national dance for over a century, holds some remarkable parallels with the development of early jazz in New Orleans. Danzón recordings were also captured and released by American record companies well before the first known recordings of jazz. These facts, in addition to the cultural exchange facilitated by migration, tourism, and of course, the horrors of enslavement and war, raise a great deal of questions about musical interactions across the Gulf of Mexico. The ensuing paragraphs will provide brief introductions to some of the primary facets of this “transnational” dialogue, along with plenty of opportunities to delve deeper through further reading and recorded examples.

A note on structure: The histories of these musics and cultures interweave, intersect, and diverge in a non-linear fashion, not unlike the collective improvisation that characterizes both danzón and early jazz. Since there is no clear, singular narrative, it makes sense to present this information in the same way — a little abstract, a little improvisatory, but always with the music and musicians at the center.

Transnational dialogues

Ethnomusicologist Robin Moore and cultural theorist Alejandro Madrid write extensively on the musical inter-influences between Cuba and New Orleans in their book Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance, specifically chapter four: “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.”[1] In fact, their work has been pivotal in shedding light on this subject, which has been largely unknown or unacknowledged by jazz historians. These inter-influences can be found in the confluence of rhythms, exchange of recordings, use of collective improvisation, geographical significance of New Orleans and Cuba as cultural hubs, musical lineage and collaborations between prominent early jazz musicians, and even the similarity of instrumentation between ensembles.

As previously suggested, jazz historiography would benefit from incorporating the many “hemispheric interrelations” that contributed to the rise of American jazz; the Cuban danzón represents just one example. Moore and Madrid’s use of the term “hemispheric interrelations” is notable in that they acknowledge the complexity and multi-directionality of these influences and interactions. Along those lines, they also discuss the idea that American jazz, in turn, impacted the evolution of Cuban dance music. (Here is an excerpt of an excellent documentary that focuses on the melding of Afro Cuban music and jazz in New York beginning in the 1930’s.)

Other scholars, such as ethnomusicologist Chris Washburne, have pointed out such musical interactions through detailed musical analysis and comparative research. Pioneering musicians allude to them as well; Jelly Roll Morton often pointed out the “Spanish tinge” as an essential element distinguishing “jazz” from ragtime.

On the other hand, Morton had a penchant for hyperbole that cast an air of disbelief around much of what he had to say — at one point he claimed to have “invented” jazz himself — so many of his gems of wisdom were taken with a grain of salt. This is a common phenomenon in the “scholarly perception” of jazz history’s primary sources — the musicians may be elderly and not entirely lucid by the time their stories are heard, or perhaps they have a particularly fanciful or grandiloquent storytelling style; the unfortunate result has been the frequent marginalization of the progenitors’ voices. That is yet another rabbit hole for a different day.

Suffice it to say that this piece attempts to strike a better balance between the objective observations of scholars and the lived experiences, subjective or otherwise, of tradition-bearers. Both are invaluable.

About danzón

The roots of danzón, “Cuba’s national dance for over one hundred years,” go back to the 1791 slave uprising in Santo Domingo. When French colonists and slaves arrived in Cuba, they brought with them the contradanza, which was then “creolized” by the musicians, dancers, and composers living there.[2] Miguel Failde’s 1879 Las Alturas de Simpson was the first premiered example of the danzón in Cuba. As African percussion textures found their way into the fabric of the music, the dance evolved from a formal contradanse to an elegant partner dance with footwork to match the syncopated beats. There is much to say about the relationship between the dance and the music, as well as the implications of the shift to partner dancing at this time, including gender, racial, and sexual dynamics;[3] but that is, again, a rabbit hole to follow at another time. (Alice would have a field day…)

Key musical elements of the genre include sectional rondo forms with dramatic textural shifts between high woodwinds/violins and brass, as well as the use of collective improvisation to build energy toward an increasingly polyphonic climactic section. The instrumentation of the danzón orchestra typically consisted of cornets, violins, clarinets and/or flutes, trombone or ophecleide, string bass, guiro, and an older style of timbales which resemble orchestral timpani (but which would evolve into the timbales featured heavily in other Latin American music, such as salsa). Additionally, the danzón features its own “clave,” or underlying rhythm, which will be discussed more later. All of these elements foreshadow other styles of Cuban music that would develop from this tradition, including the son, mambo, and cha cha cha.[4]

Danzón’s popularity spanned the Caribbean and made its way to New Orleans first through published sheet music and performances by traveling musicians. Word of this Cuban dance “craze” reached American recording companies around the turn of the twentieth century. And, in fact, according to Moore and Madrid, the Cuban danzón was “one of the first musics created and recorded by African descendants in the Americas with early Edison cylinders and 78 rpm records of the music predating jazz discs by more than a decade.”[5] That statement alone should be enough to entice anyone with an interest in early jazz into further study. Detailed information on the publishing and dissemination of those recordings is scant, but they were recorded prolifically and distributed by the American companies Victor, Edison, and Columbia from 1905 through the 1920s. So, it is quite possible that fledgeling musicians in the early 20th century had access to these recordings and were influenced by the instrumentation, texture, rhythm, and spirit of that music. There is also evidence of the danzón reaching audiences in New Orleans in the late 19th century through performances by Mexican Military bands. Performances of the danzón are featured in concert programs in the Daily Picayune, a local newspaper printed from 1837-1914.[6]

Here are two albums highly recommended for further listening: The 1999 Arhoolie release The Cuban Danzón — before there was Jazz: 1906-1929, and 1982 Folkways release, The Cuban Danzón: Its Ancestors and Descendants.

Musical lineage

Beyond musical exchange via sheet music, visiting performers, and possibly recordings, there are also striking “trans-national” Circum-Caribbean connections to be found in the musical lineage of and collaborations between prominent musicians in the early jazz tradition. By now, we’ve established that New Orleans served as a major epicenter in the formative years of jazz, so if we want to know more about the early bubblings of that music, we should investigate the ways in which pioneering jazz musicianers[7] learned and developed their own playing and style.

One such pioneer who both studied and collaborated with musicianers who had Cuban connections was the great reed-man Sidney Bechet. Born and raised in New Orleans, he was one generation removed from those musicians said to have “invented” jazz, and therefore had the opportunity to hear and collaborate with many musicians about whose sound and style we can only speculate (such as the famous cornetist, Buddy Bolden). Bechet was of Creole ancestry, raised in a musical family, and would become one of the most accomplished and highly respected soloists to emerge from the early jazz tradition. He gives an expansive and poetic narrative of his experience as an early jazz innovator in his autobiography Treat it Gentle (which should really be required reading in any jazz history course, for the record). He was primarily self-taught but did study with clarinetists such as George Baquet, “Big Eye” Nelson, and Lorenzo Tio Jr.. Bechet writes, “Lorenzo Tio, he gave me lessons. I hung around his house a lot. We used to talk a lot together, and we’d play to all hours. Lorenzo Tio, he was real good to me.”[8]

Tio and his brother were part of a colony of Cuban refugees in Mexico who relocated to New Orleans in 1884, bringing with them various Cuban Danzas, which they played with the Eighth Regiment Band of the Mexican Cavalry.[9] Other pupils of the Tio family include Barney Bigard, Omer Simeon, and Jimmy Noone. Lorenzo Tio Jr. often collaborated with cornetist Manuel Perez, who may have been born in Cuba or in New Orleans (sources conflict on this information, but either way, he is another connector between the two cultures). Bechet also praises Manuel Perez’s playing, saying, “He was a musicianer, he was sincere.” And he played “much better cornet than Buddy [Bolden],”[10] who is almost always cited in mainstream jazz historiography as the originator of jazz.

Perez was also highly influential as an educator. Trumpeter Natty Dominique studied with Perez since he was a boy and said, “Mr. Manuel Perez — that’s an accomplished musician and there’s not another teacher like him in the world, for me, because he’s a cornetist and a number one genius! And I regret the day that Mr. Perez died, because I loved him as a daddy. When I look up, his picture comes before me and I appreciate all he has done for me.”[11]

Another passage may also speak to the residual influence of danzón and sets Manuel Perez apart as a bandleader. According to Bechet, the way he led his celebrated “Onward Brass Band” was especially conducive to dancing, perhaps due to a greater focus on ensemble playing or some particular rhythmic cohesion that inspired movement in an irresistible way. Some members of the Onward Brass Band, as it happens, did a stint with the Ninth Volunteer Infantry, an all-African American unit who fought in the Spanish-American War. They were in Cuba for about six months between 1898-99. Who knows what sorts of sounds and sensibilities they may have brought home to New Orleans.[12]

…the Onward was a brass band that usually just played for parade music, music for marches. But people would start to listen to the band and pretty soon some of them would go out in the middle of the grounds and start dancing, and then some more would join them, and before long, everybody would be dancing…It’s not easy to dance to a brass band, but Manuel had a way of playing different when he came to the fairgrounds. He’d take his brass and he’d really make it danceable. What he’d do is change the arrangement. He’d play it so it wasn’t a matter of everybody taking his chorus; the important thing it would be the tempo and the way each player carried the tempo. He’d keep them together and he’d keep them playing with a real swing to it. He’d have twenty, twenty-five brass men playing like one together…all the phrases together, just like you’ve got a really well-trained chorus of people to speak a part for the stage and they’re all talking together and stopping together so you don’t miss a word. And when you’d hear that it would give you a feeling that would be making you want to dance. It would just take your feet and make them go like it was something inside you.[13]

Sidney Bechet

Passages like these give us unique portraits of the musicians we’ll never get to hear. We can also glean something about the way those musicians might have sounded by combining those portraits with other similar recordings of the time. In fact, one of the benefits of having access to those early danzón recordings is that they can give us some actual aural insight, tangential as it may be, into some of the missing links in the development of jazz. Bandleader, multi-instrumentalist, acoustic recording expert, and jazz historian Colin Hancock cites the playing of Cuban cornetist/bandleader Pablo Valenzuela and his orchestra as a potential source from which to gain insight into the sound of the famed Buddy Bolden band — “originators of jazz.” The band, and Bolden himself, have been lionized through decades of storytelling, and yet they remain shrouded in mystique due to a lack of surviving recordings. (Some accounts suggest the Buddy Bolden band was recorded at some point, but those cylinders have not been found.)

In attempts to better understand the roots of jazz, Hancock applied his expertise to the project of “re-enacting” the lost Buddy Bolden cylinders. He brought together a group of seasoned musicianers well-versed in the early jazz style to interpret the music and then recorded them using the same technology that was used to capture the earliest jazz, ragtime, and danzón. Listening to those danzón recordings, specifically of Pablo Valenzuela’s orchestra, gave him crucial insight on how to carry out the project with greater depth and authenticity. Hancock writes, “An Afro-Cuban, Valenzuela was among the first in Cuba to record the local danzón style and possessed a strong lead attack and tone, traits that more than one account attribute to Bolden as well. Moreover, the Orquesta de Pablo Valenzuela used a startlingly similar instrumental lineup as Bolden’s, with a string bass and drums in the rhythm section, a trombone, and multiple clarinets.”[14]

Of course, one cannot ignore the musical lineage carried forward by the descendants of these pioneers, who are making music today. The family names of Santiago, Braud, Batiste, Marsalis, and Brunious, for instance, represent musical dynasties of New Orleans that continue to bring that rich and storied history to the music they make in the present. Wendell Brunious, the great trumpeter and youngest musician to lead the world-renowned Preservation Hall Jazz Band, plays every Tuesday night at Dos Jefes, a cigar bar on Tchoupitoulas St. in New Orleans. You can sit in that smoke-filled club and hear generations of music flow from his horn, punctuated by delightfully groan-worthy jokes and playful banter.

Mr. Brunious also spent time making music not only in Cuba but with Cuban musicians who would come through New Orleans. He says they hired him because he could read music, and playing in those situations exposed him to salsa, mambo, cumbia, and merengue. He learned the rhythms and dances associated with those musics, and that became part of his soundscape and sensibility. His father was trumpet master John Brunious. His uncles, Burnell and Lester Santiago, were both great pianists. His great-uncle, Willie Santiago, was one of the most in-demand banjo/guitarists of the early jazz era in New Orleans, and a contemporary of Manuel Perez.[15] His nephew, Mark Braud, also a distant relative of legendary Duke Ellington Orchestra bassist Wellman Braud, now leads the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. Mark Braud also helped bring these multi-generational, trans-national connections full circle when he traveled with the band for the journey documented in the award-winning film, A Tuba to Cuba.

Creative director and tuba player for the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Ben Jaffe, is also part of this family tradition — his father founded what is now Preservation Hall and played tuba with the prestigious Olympia Brass band led by Harold Dejan. The musicians who carry on this tradition in New Orleans recognize the importance of their ties with Cuba and Afro-Cuban music in a way that mainstream jazz historiography largely ignores. In A Tuba to Cuba, Jaffe says, “The roots of our music are firmly planted in Cuba.” He also shares a sentiment that resonated with the band from Yohandri Arguin, one of the Cuban trombone players they met on their journey: “Music is a way for us to connect with our past and give our ancestors a voice.” A theme emerges as the film progresses and the band continues to travel from Havana to Santiago and eventually to Cienfuegos: the importance of musical lineage is yet another commonality between Cuba and New Orleans. As Jaffe says, “It’s important to have an older generation of culture bearers to ensure the survival of the tradition.” Likewise, Jorge Vistel Columbié, the leader of the Piquete Tipico de Cuba, a modern ensemble that has continued to perform danzónes both new and old for the last fifty four years, says “Our founders were older musicians…We always have young people in the group. That’s very important because that’s how we are able to preserve the music.” Perhaps this strong musical lineage and culture of mentorship instills a different set of values — the importance of family (blood or otherwise) and community. And it’s not just in the way the music is passed down, it’s in the way the music is played and experienced — collective improvisation takes precedence over the soloist and they rhythm is always conducive to dancing. It is inherently participatory. It connects people and builds community. Ben Jaffe sums this up beautifully as he muses about lessons learned from his mentor, and his time in Cuba: “Something I’ve learned from Charlie Gabriel is that musical conversation cancels out complication. You really sense that in Cuba. It’s important to engage in a dialogue. You get more out of life when at your core you believe in the value of building bridges and that’s something we can all do.” [16] This is all to say that the musical families of New Orleans and Cuba are attentive stewards of the tradition and the values associated with it — passing their shared knowledge and experience along; through that, the web grows denser but never loses touch with the connections that brought it into being.

“The clave of jazz”

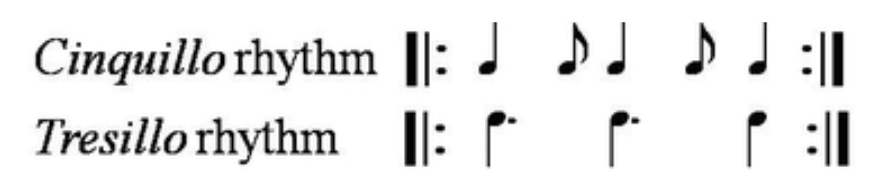

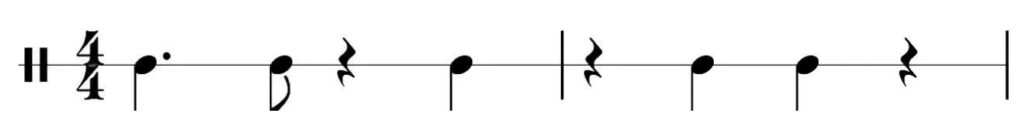

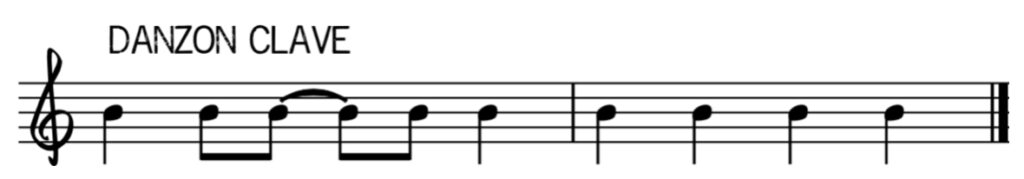

If we consider the styles of music we’ve discussed so far — danzón, ragtime, jazz, and their antecedents and descendants — more than anything, it’s rhythm that gives them each their own distinct character. And it’s not just a rhythm you can write down. It’s a feeling, a sensibility full of nuance flavored by lived experience. Wendell Brunious says, “You can’t write that feeling — it’s something you just get in your soul through respect and association.” There’s a rhythmic concept that forms the backbone of Afro-Cuban music called clave — Spanish for “key” and aptly named, as it provides a rhythmic foundation that “locks” the music together. The clave also provides us with another key to tracing musical connections throughout the Circum-Caribbean. In his thoroughly researched article “The Clave of Jazz: A Caribbean Contribution to the Rhythmic Foundation of an African-American Music,” Christopher Washburne provides concrete evidence of the intersections of jazz and Caribbean music in his clearly articulated analysis of musical examples. He notes the use of cinquillo and tresillo rhythms as “rhythmic cells” in the music (see below) and demonstrates the presence of the son clave (3-2 or 2-3), both explicit and implicit, in a wide array of jazz selections.[17]

The tresillo seems to be the foundation of many of these rhythms: The “Charleston rhythm” heavily present in jazz (and the accompanying dances — solo and partnered) is simply the first half of the tresillo. The tresillo has also become extremely common in American music and can be found anywhere from rock ’n’ roll and R&B to modern New Orleans Brass Band music and beyond. Wendell Brunious noted those connections as well, when discussing the various clave patterns he encountered in his experience playing Caribbean music and “Latin Jazz.” He said, “When you can do those rhythms, it’s just like playing the bass drum in a New Orleans band.”[18]

The cinquillo is an embellishment of the tresillo, and the danzón clave consists of a bar of cinquillo plus a bar of quarter notes. Washburne sees developing a deeper understanding of these rhythms as “the first step in attempting to bring jazz antecedents into sharper focus.” He continues by aptly stating, “to say that ‘the rhythm in jazz is African’ is much too simplistic.”[19]

Figure 2: 3-2 son clave

Figure 3: Charleston Rhythm

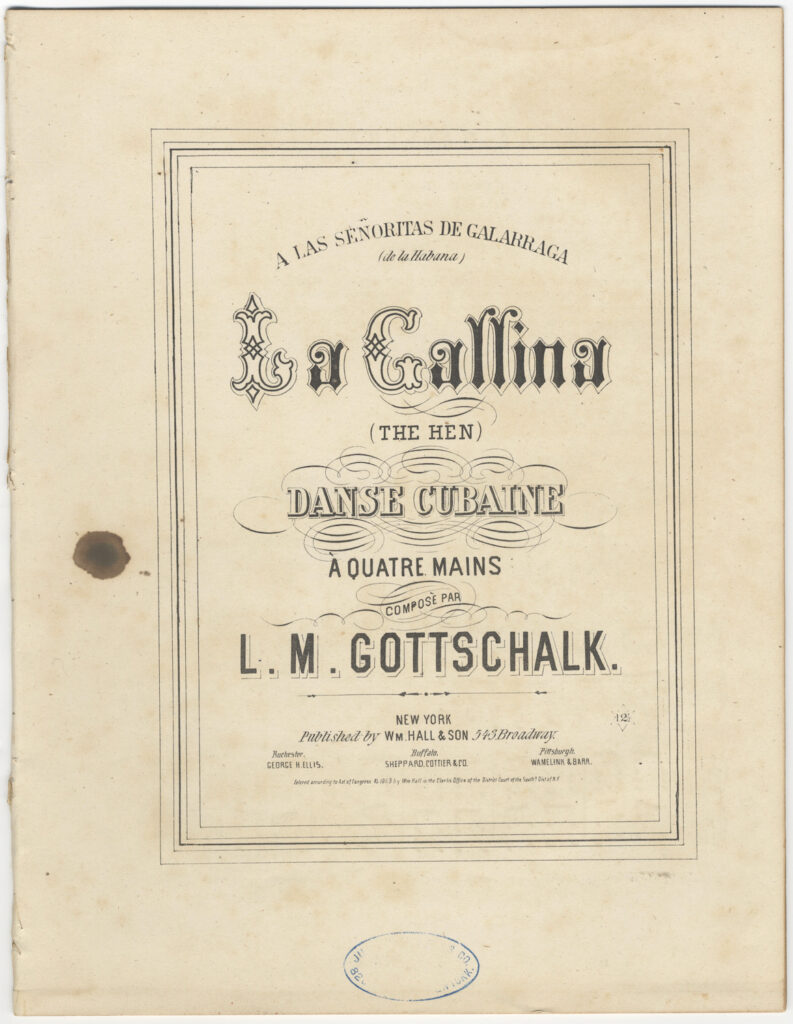

One New Orleans-born composer who became enamored with the rhythms and music of Cuba — and incorporated some of them into his music — was piano prodigy and composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Gottschalk studied music with his grandmother and nurse, both of whom were natives of Saint Domingue, and he also spent considerable time in Cuba in the mid-19th century. He would subsequently “produce the first concert music inspired by the contradanza, danza, and related forms.”[20] His music melds the rhythms of Congo Square with Afro-Cuban rhythms and European melodies, providing a foundation for ragtime and jazz to come.

Jelly Roll Morton also famously incorporated these rhythms into many of his compositions, again making a point that the “Spanish tinge” was required for jazz to have the right “seasoning.” Several of Morton’s compositions, including “New Orleans Blues” and “The Crave,” utilize the tresillo, habañera, and cinquillo rhythms. However, given the wealth of evidence to support Morton’s assertions about the importance of this rhythm, mainstream jazz historiography has stubbornly disregarded the Caribbean connection to Early Jazz. John Szwed, anthropologist, author, and jazz scholar eloquently summarizes the oversight:

What Jelly Roll saw as an enduring and integral part of American music, later commentators would dismiss as an imported craze from Mexico, say, or Cuba. The music that he thought called for a pan-American comparative perspective, these mid-century critics treated as an accidental and limited meeting of American and exotic forms. But in retrospect, it appears that Morton was correct. Those who ignored him erected a false evolutionary perspective that emphasized jazz as a radical break from the musical past, and by excluding the whole range of folk, ritual, and foreign musics from jazz history, all of the music of the United States was grossly oversimplified.[21]

At this point the use of Afro-Cuban rhythms in American music has become ubiquitous, and perhaps jazz was the first point of entry for that cross-pollination. But, what if we also considered the similarity between clave and swing as rhythmic concepts? (Swing as a rhythmic concept is possibly the deepest rabbit hole yet. Suffice it to say, it’s extremely nuanced, and there are a great deal of strong opinions on the subject within the jazz community.) To Cuban musicians, in order to play the music with the right feel, you have to play “in clave.” To jazz musicians, in order to play the music with the right feel, you have to “swing.” Both styles require listening and learning through immersion and mentorship to really do them justice. In this way, Cuban and jazz musicians share a fundamental value for the way the music feels.

Collective improvisation

Another unique aspect that jazz and danzón have in common, and an integral unifying element in the dialogue between the styles, is the use of collective improvisation or “polyphonic weave.” This style of playing is explored more thoroughly in reference to Latin American music, for example, in the mambo sections of the Cuban Son, which has roots in the danzón. The “mambo” section — or, as Cuban musician and bandleader Arsenio Rodriguez referred to it, the “diablo” section — is another related, unifying element; there is intrinsic value in the building of energy towards a climactic moment of textural density and intensity (the “diablo section”), which is then reflected on the dance floor, highlighting the symbiotic relationships between dance and music, and audience and musician. The music is a vehicle for a transcendent collective experience.

Those who have experience in collective improvisation know that there is a particular magic and flow to its successful execution. It is not an easy feat to improvise polyphonic lines with other musicians simultaneously in a way that culminates in an exciting, cohesive, harmonious whole. It requires a high level of sensitivity and intuition on behalf of the musicians who do it best. David Garcia discusses this concept in the following passage from his book, Arsenio Rodriguez and the Transnational Flows of Latin Popular Music, which can easily be applied to the “polyphonic weave” present in traditional jazz, or “hot jazz” collective improv.[22]

In 1951 Fernando Ortiz gave his own interpretation of the essence of the mambo in which he underscored the actual rhythmic structure in the forms of interwoven patterns: ‘It is all nothing more than a link of lines coordinated in a weave that is composed of the spontaneity of each rhythm, individually played to each musician’s whim, both whose threads are crossed and interlaced into one warp … Although arbitrary and capricious, there is no anarchy or lack of structure, rather a wonderful concert of individual freedoms taken to the maximum within a minimal but unshakable structural arrangement…’[23]

When that “concert of individual freedoms” is firing on all cylinders, especially when musicians and dancers are all involved, the collective effervescence that occurs is indescribable. Again, the fact that both of these musical styles involve a healthy component of collective improvisation is a testament to the importance of the feeling that the music evokes, as well as its communal nature. After his session playing with the musicians of the Piquete Tipico Cubana, Mark Braud said, “the spirit of the music is so similar, so we were able to go in and just fall right in. They were so welcoming just like we are in New Orleans.” It’s not just music for music’s sake — it’s a way to connect and engage with others.

Geographical significance

New Orleans is sometimes referred to as the northernmost Caribbean city — its position, nearly melting into the Gulf of New Mexico, made it a hub for all manner of cultural exchange. A trade conduit for goods, services, enslaved people, soldiers, and refugees brought a steady stream of Afro-Caribbean culture to New Orleans, and sometimes from New Orleans back to Cuba, for centuries. (Read more about the significance of this route in this article by Nick Douglas, author of Finding Octave: The Untold Story of Two Creole Families and Slavery in Louisiana. Learn more about the forced relocations of enslaved people to New Orleans here.)

Chase Watkins of the American Association of Geographers traces the history of New Orleans music[24] using geographic locations as a springboard to discuss the growth of these musics. Congo Square was the “hearth of musical culture in New Orleans” as it was “the first and only sanctioned gathering place for enslaved people in the antebellum United States — beginning as early as the 1740s.” I would be remiss not to share at least a portion of the story from great jazz pioneer, Sidney Bechet, about his grandfather, Omar, and Congo Square.

That was how the Negro communicated when he was back in Africa. He had no house, he had no telegram, no newspaper. But he had a drum, and he had a rhythm he could speak into the drum, and he could bring them to him. And when he got to the South, when he was a slave, just before he was waking, before the sun rode out in the sky, when there was just that morning silence over the fields with maybe a few birds in it — then, at that time, he was back there again, in Africa. Part of him was always there, standing still with his head turned to hear it, listening to someone from a distance, hearing something that was kind of a promise, even then… and when he awoke and remembered where he was — that chant, that memory, got mixed up in a kind of melody that had a crying inside itself. The part of him that was where he was now, in the South, a slave — that part was the melody, that part of him that was different from his ancestors. That melody was what he had to live, every day, working, waiting for rest and joy, trying to understand that the distance he had to reach was not his own people, but white people. Day after day, like there was no end to it. But Sunday mornings it was different. He’d wake up and start to be a slave and then maybe someone would tell him: ‘Hell, no. Today’s Sunday, man. It ain’t Monday and it ain’t Tuesday. Today’s free day.’ And then he’d hear drums from the square. First one drum, then another one answering it. Then a lot of drums. Then a voice, one voice. And then a refrain, a lot of voices joining and coming into each other. And all of it having to be heard. The music being born right inside itself, not knowing how it was getting to be music, one thing being responsible for another. Improvisation, that’s what it was. It was primitive and it was crude, but down at the bottom of it — inside it, where it starts and gets into itself — down there it had the same thing there is at the bottom of ragtime. It was already born and making in the music they played at Congo Square.[25]

Sidney Bechet

The Congo Square that exists today is a small, unassuming cobblestone plaza tucked away next to Armstrong Park on Rampart Street at the edge of the French Quarter. It is not on the exact site where those early gatherings occurred, but the air around it still feels heavy and alive with the weight of collective memory. Centuries-old oak trees stand steadfast around it, branches blanketed in moss and creased like an elderly grandmother’s outstretched arms. The music seems to have a home. A sacred hearth, indeed.

Geography plays an equally important, yet often overlooked, role in the development of the music as the people who created it — the trade routes with the Caribbean, the neighborhoods that hosted the dances and picnics that would employ countless musicians, the brass bands that inhabited the streets through the development of the second-line parade as a physical conveyance of the body and spirit through mourning and celebration, the riverboats that carried the music up the Mississippi and helped spread the youthful sounds of jazz to the Midwest and beyond. Watkins writes, “The genius of New Orleans’ music springs not from the spontaneous epiphanies of a few talented individuals, but instead crystallizes from the city’s fluid connections to other places. As the confluence of the French, Spanish, and Black Atlantic Worlds, New Orleans has long provided an inclusive venue for the integration of diverse cultural forms.”[26]

Moving forward

Mainstream jazz historiography holds to a narrative with a neat and tidy point of origin, and a linear trajectory from then to now. Many traditional/early/hot jazz/swing players view their role in the music as re-creationists, perhaps transporting listeners to another era by performing note-for-note the music from a recording. Indeed, there is value in historical preservation, but attachment to fixed, false notions of “the way things were” is not the way we evolve. Thankfully, there is also a healthy community of musicians, dancers, listeners, and scholars, who take a different view — that history is more like an interconnected web than a straight line, and that we are part of a living, breathing tradition which can be made fresh with every new performance. Wendell Brunious says, “The whole art form is a growing entity.” Who wouldn’t want to be a part of that growth in some way?[15]

Curiosity, fascination, and a search for connections with an ever-growing musical ancestry were the guiding forces behind this research. This intrinsically-motivated and non-linear approach to studying history has the potential to expand our worldview, and perhaps introduce some new music to our soundscapes that may come into play in unexpected ways. Since the “trans-national” nature of musical interaction is not often included in jazz historiography and discourse, building awareness of this aspect of jazz heritage will help develop a more holistic view of the art form’s vibrant, ongoing evolution to audience members and musicians alike. This line of discussion and research will not only shed light on strands of the jazz history “web” that were previously in the shadows, but will also amplify voices that were previously marginalized and draw attention to jazz performance practice as a living tradition. And it will serve to build community through collective, spontaneous music-making and dancing. The musicians in this community are not attempting to recreate the source recordings, but rather to demonstrate how a historically informed performance can generate something that honors a tradition by creating something new — honoring a tradition by bearing it forward.

Musical examples

Las Alturas de Simpson (03:31) Ref. La Orquesta Folklórica Nacional Cubana 1982

Written in 1879 by Miguel Failde (1852-1921), Las Alturas de Simpson is considered to be the first danzón ever written. Cornetist and composer, Miguel Failde Pérez was born in the Cuban province of Matanzas and would become the “father of the Cuban danzón.” In the same way that American dance and music styles evolved symbiotically, the Cuban danzón evolved due to a shift from the “stiffer, up-tempo choreography of the danza” toward the more sensual and expressive couple dance. And the music followed suit. Additionally, the danzón added a third contrasting section, which included more rhythmic syncopation. These three sections were referred to as: Introduction, Clarinet Trio, and Metal Trio (meaning brass instruments).

El Automóvil (03:04) Ref. Orquesta de Enrique Peña 1909

This piece shows a playful quality common in danzónes of this time period — “art imitating life” — as the percussion instruments imitate vehicle sounds and the orphecleide (or trombone for this concert) simulates the “horn.” Apparently in 1909, automobiles were still a novelty in Havana. On the first known American jazz recording from just a few years later in 1917, the Original Dixieland Jazz band plays Livery Stable Blues, and in a similarly playful manner, imitates the “mundane” sounds of farm life.

Happy Hobbs Two-Step (02:07) Ref. Orquesta de Pablo Valenzuela 1907

During a 1906 session, Valenzuela’s Orquesta also recorded several ragtime numbers, including the Happy Hobbs Two-Step. The bassist is playing a clear “two-beat” rhythm, and the rhythm section abandons their typical danzón feel in favor of a convincingly authentic “proto-jazz” drive. Hancock reflects that “though it was performed hundreds of miles away, when one listens to this recording it is not hard to envision Bolden’s band playing this same tune at a Johnson Park picnic or Funky Butt Hall dance.”

La Paloma (4:12) Ref. Paul Whiteman 1928

This reference recording is representative of a very polished, non-improvisatory “early Jazz” rendition of one of the most popular tunes of the early recording industry. Although the tune is of Mexican origin, its popularity demonstrates the American fascination with Latin American music in the early 20th century that continues today. It was typically performed with a Habañero bass pattern. The Paul Whiteman arrangement does feature quite a few textural shifts which are similar to those one would hear in the early danzón recordings. It even includes a “Spanish” guitar and steel guitar duet, several key changes, a section in which Bix Beiderbecke swings the melody over a “four-to-the-bar” feel (still with the habañero pattern, but played by a low reed), and a coda that sounds almost cinematic to modern ears.

Mamanita (04:09) Ref. Jelly Roll Morton 1938 Alan Lomax recording, disk 6

This piece demonstrates what Jelly Roll described as “The Spanish Tinge,” essential to early jazz. It features tresillo bass line throughout — and one could argue a danzón clave can be found as a composite between left and right hand. One can easily hear the way this rhythm became part of the life blood of New Orleans music, as it can still be heard on the streets in the bass lines of the brass bands playing today.

Under the Creole Moon (3:19) Ref. Noble Sissle and His International Orchestra 1934

This track was recorded in Chicago October 15, 1934 by Noble Sissle and His International Orchestra, which included Noble Sissle (vcl, dir), Wendell Culley, Demas Dean, Clarence Brereton (tp), Chester Burril (tb), Sidney Bechet (cl, ss), Harvey Boone (cl, as), Ramon Usera (as, vln), Harry Brooks (p), Howard Hill (g), Edward Coles (sb), Jack Carter (d), Billy Banks, Laviada Carter (vcl). The recording is interesting, as it features a consistent tresillo bass line, and the drummer is hinting at a cinquillo pattern throughout. The instrumentation, textural shifts, and melodic and rhythmic treatment are also reminiscent of the danzòn style. It is unclear to what Noble Sissle was referring when he renamed his ensemble “International Orchestra,” as this is the only “International” tune recorded under that name.

Tropical Mood Rhumba (3:06) Ref. Sidney Bechet’s Haitian Orchestra 1939

Given this cross-cultural perspective, it should come as no surprise that music of the Circum-Caribbean would find its way into legendary New Orleans reed player, Sidney Bechet’s, soundscape. He wrote his “Haitian Suite” in 1915, though it wasn’t recorded until 1939. [6] According to Willie “the Lion” Smith, who played piano on the 1939 session, Bechet met him on the St. Nicholas Avenue in New York and said, “We should make some West Indian records because everyone is laughing and enjoying the calypso songs.” So he formed the “Haitian Orchestra” for the Variety label and cut several sides, which biographer John Chilton calls “the most bizarre recording date of Bechet’s career.” In addition to Smith and Bechet, the band consisted of Kenneth Roane on trumpet (also the arranger for the session), Olin Alderhold on string bass, and Leo Warney on drums. Though the album did not sell well, musicologist Ernest Borneman called the session “the first deliberate reunion of jazz and Afro-Spanish folk music in history.” Although the band assembled for the session was dubbed the “Haitian Orchestra,” the music recorded represents a melange of styles. One tune in particular more closely resembles a Cuban danzón. It is listed under several different titles, but it is most commonly referred to as Tropical Mood – Rhumba.

Porto Rico (3:13) [sic] Ref. Bunk Johnson and Sidney Bechet 1945

This performance is based on the recording made in New York March 10, 1945 by Bunk Johnson — Sidney Bechet and Their Orchestra: Bunk Johnson (tp), Sandy Williams (tb), Sidney Bechet (cl), Cliff Jackson (p), Pops Foster (b), Manzie Johnson (d). This is yet another example of American jazz musicians referencing Caribbean music and blending it seamlessly with traditional New Orleans-style collective improvisation and 4-beat “swing.” The tune opens with a minor key danzón-esque section with a tresillo pattern in the bass and a shift to major and 4-beat swing, staying there for the remainder of the tune.

Panama (2:28) Ref. Jelly Roll Morton’s Seven 1940

In the New Orleans Rhythm Kings 1922 recording of this tune, there is some evidence of danzón clave between bass and banjo/woodblock, but otherwise it is a relatively straight traditional jazz recording. However Jelly Roll Morton does incorporate the “Spanish Tinge” or tresillo rhythm that is peppered throughout his 1940 version of the tune. This “hot” piece demonstrates the culmination of Circum-Caribbean dance music with early American Jazz, as interpreted by roots jazz collective improvisers.

[1] Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore. “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.” Chapter 4 in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] John Santos. Liner notes for The Cuban Danzón: Its Ancestors and Descendents. Recorded January 1, 1982. Folkways Records, 1982, Streaming Audio. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C71648.

[3] Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore. “Cachondería, Discipline, and Danzon Dancing” Chapter 6 in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[4] William Gradante and Jan Fairley. 2001 “Danzón.” Grove Music Online. 11 Apr. 2019. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.libproxy.txstate.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000007204.

[5] Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore. “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.” Chapter 4 in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 119.

[6] ibid. 127-28.

[7] Bechet and others used the term “musicianer” to refer to other professional musicians. It seems to be both a term of endearment and respect.

[8] Sidney Bechet. Treat it Gentle: An Autobiography. (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 79

[9] Leonardo Acosta. Cubano Be Cubano Bop: One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2003) p. 22.

[10] Sidney Bechet. Treat it Gentle: An Autobiography. (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 83.

[11] Bill Russell. “Natty Dominique.” Chapter 16 in New Orleans Style. (New Orleans: Jazzology Press, 1994), p. 146.

[12] Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore. “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.” Chapter 4 in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 130-131.

[13] Sidney Bechet. Treat it Gentle: An Autobiography. (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 216

[14] Colin Hancock. “The Bolden Cylinder Project.” The Jazz Archivist. Vol. XXVIII (2015), p. 28. Read more about the Bolden Cylinder Project here.

[15, 18] Wendell Brunious (trumpeter and long-time leader of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band) in discussion with the author, January 2022.

[16] A Tuba to Cuba. Directed by T. G. Herrington and Danny Clinch. (New Orleans and Cuba: Blue Fox Entertainment, 2018), Streaming on Amazon Video

[17, 19] Christopher Washburne. “The Clave of Jazz: A Caribbean Contribution to the Rhythmic Foundation of an African-American Music.” Black Music Research Journal 17, no. 1 (1997): 59-80. doi:10.2307/779360.

[20] Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore. “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.” Chapter 4 in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 217

[21] John Szwed. “Doctor Jazz.” Liner notes for Jelly Roll Morton: The Library of Congress Recordings By Alan Lomax. Recorded January 1, 2007. Rounder Records, 2007, Streaming Audio. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C2155239. p. 29-30

[22] Incidentally, the nomenclature of “hot” and “cool” as related to music energetically, is another parallel in the discourse around jazz and Latin music.

[23] David Garcia. Arsenio Rodríguez and the Transnational Flows of Latin Popular Music. Studies In Latin America & Car. Temple University Press, 2011. https://books.google.com/books?id=4e5GF9NwHucC. p. 47

[24, 26] Chase Watkins. “Essential Geographies of New Orleans Music.” American Association of Geographers. http://news.aag.org/2017/08/essential-geographies-of-new-orleans-music/

[25] Sidney Bechet. Treat it Gentle: An Autobiography. (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 7-8

Bibliography

Acosta, Leonardo. Cubano Be Cubano Bop: One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian

Institution, 2003.

Bechet, Sidney. Treat it Gentle: An Autobiography. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002.

Chilton, John. Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Collier, James Lincoln. 2001 “Bechet, Sidney.” Grove Music Online.6 Mar. 2019.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-

9781561592630-e-0000002457.

Garcia, D. Arsenio Rodríguez and the Transnational Flows of Latin Popular Music.

Studies In Latin America & Car. Temple University Press, 2011. https://books.google.com/books?

id=4e5GF9NwHucC.

Gradante, William, and Jan Fairley. 2001 “Danzón.” Grove Music Online. 11 Apr. 2019.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.libproxy.txstate.edu/grovemusic/view/

10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000007204.

Hancock, Colin. “The Bolden Cylinder Project.” The Jazz Archivist. Vol. XXVIII(2015): 26-37.

Herrington, T.G. and Danny Clinch, dir. A Tuba to Cuba. New Orleans and Cuba: Blue Fox Entertainment, 2018.

Streaming on Amazon Video.\

Madrid, Alejandro L. and Robin D. Moore. “The Danzón and Musical Dialogues with Early Jazz.” Chapter 4

in Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press,

2013.

Moos Pick, Margaret. “The Tio Family: A New Orleans Clarinet Dynasty.” Riverwalk Jazz. Program 259. 2006.

http://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/tio-family- new-orleans-clarinet-dynasty.

Santos, John. Liner notes for The Cuban Danzón: Its Ancestors and Descendents. Recorded January 1, 1982.

Folkways Records, 1982, Streaming Audio. https://

search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C71648.

Spottswood, Dick, and Cristóbal Díaz Ayala. Liner notes for The Cuban Danzón Before There Was Jazz: 1906-1929.

Recorded January 1, 1999. Arhoolie Records, 1999, Streaming Audio.

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C386100.

Szwed, John. “Doctor Jazz.” Liner notes for Jelly Roll Morton: The Library of Congress Recordings By Alan Lomax.

Recorded January 1, 2007. Rounder Records, 2007, Streaming Audio.

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C2155239.

University of California, Santa Barbara. “Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project.” Edison Gold Moulded

Record: 18948.. Orquesta De Pablo Valenzuela. UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive. November 16, 2005. Accessed

April 29, 2019. http:www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder16115.

Washburne, Christopher. “The Clave of Jazz: A Caribbean Contribution to the Rhythmic sic.” Black Music Research

Journal 17, no. 1 (1997): 59-80. doi:10.2307/779360.

Watkins, Chase. “Essential Geographies of New Orleans Music.” American Association of Geographers.

http://news.aag.org/2017/08/essential-geographies-of-new-orleans-music/