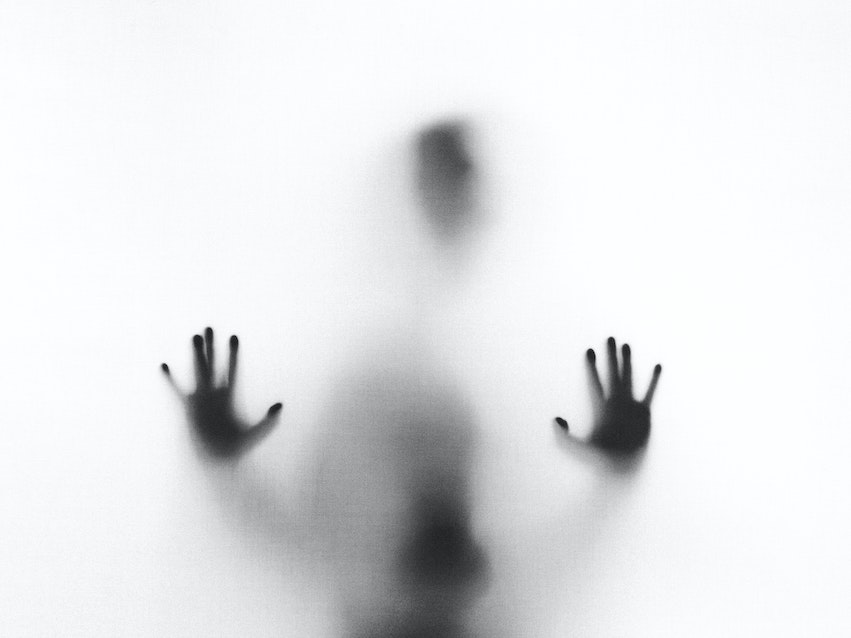

Imposter syndrome: the monster looming over the heads of everyone who feels as though their talent and ethos are put into question by unseen forces. In the realm of our chosen professions, imposter syndrome leaves us wondering if we are even good enough to do what we feel called to do or if we belong somewhere else instead. Is everyone else smarter, brighter, or better? I think back to Useni Eugene Perkins’ poem “Hey Black Child” and how this text continues to affect me professionally and personally. Growing up, my mother always told me I was intelligent and would be capable of anything if I kept a sound mind and continued walking in my purpose; this allowed me to start building confidence from an early age and recognize when I was not being challenged in my academic pursuits. Little did I know, my mother’s words were sounding in antiphony to the words of others, like Perkins. The first time I heard/read this poem was in middle school; I had yet to acquire the necessary skills to synthesize the material, so I read it superficially and treated it as such. Now looking back at who I was in middle school compared to who I am now, I realize just how much I needed to read that.

As a Black womxn in academia, I often feel as though my credibility is being questioned. Every day I grapple with the idea that I might not belong in this space dominated by those who look so different from me in terms of race and gender identity or seem to perform so much better than I do in scholarship and music-making. But, who is putting these thoughts in my head? Is it academia or is it me? It might be both. If I’m being completely honest, though we’ve come a long way from where we once were, academia still has a long way to go in terms of equity and justice.

Lately I find myself reading Perkins’ poem a little differently, emphasizing different words and stressing the “rhetorical” questions being asked throughout the stanzas. Instead of assuming the questions are rhetorical, I’m choosing to look at them as hypophora. I am the Black “child” (young in my career) that needs to find my sense of self, my identity, and my purpose in life. I need to know who I am, believe in it, and act on it. I need to know I can be what I want to be if I try to be what I can be, and Perkins is telling me that. Questions posed such as, “Hey black child, do you know where you are going?,” can be answered with “I’m on my way to change the world. I’m going to learn what I can learn to be the best I can be.” I can do so much in the fine arts world and, though my mom has been telling me that for years, I’m just now starting to realize that she was on to something: reading this poem as an adult has made me realize that while there are pressures that may hold me back, the biggest one is my own mind. In the last stanza of the poem, Perkins reminds us that if we learn what we must learn, and do what we can do, our nation will be what we want it to be. For my “nation” — the spaces I occupy most — to be what I want it to be, I must find my own gratification in what I do as a musician and scholar and help others see the value in what I do for a living.

As artists living in this post-pandemic world where society has shown us just how expendable they believe the arts and BIPOC to be — from shutting down live theatre and performance halls to police officers unjustly murdering people of color — I can confidently say that we, as artists and individuals of other marginalized groups, all suffer from imposter syndrome. Can we prove that we are worthy of being here, or are we really expendable? My response, seeing my art and my life being undervalued, is to place a heavy emphasis on proving to society that people like me belong. . . notwithstanding the monster that forces me to believe, rather convincingly, that there are other people better suited to take on this sizeable task of justifying artist and minority belonging. I am the Black child that can make tomorrow’s nation exactly what I want it to be. It shouldn’t matter if others validate us — though it is nice — because we like what we do and we know that we are smart, capable, and resilient. And, while that monster will continue to bare his teeth whenever we do what we feel called to do, what we know matters, we recognize that he is nothing more than an anthropomorphism of societal pressures that make him appear unconquerable. And every day, we may choose to respect ourselves as artists and fight for the “nation” — the spaces we occupy most, the communities we create together, both artistic and otherwise — we wish to live in.

So now, I ask you to join the conversation: Hey child, is that monster still telling you that your knowledge, expertise, and feelings are invalid? What does that feel like? How can you counter that, both in yourself and how you interact with others?