Freedom and fullness of expression are of the essence of the art.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

It feels a little trite, at this point, to say that 2020 and its washout changed how I think about my own art and the repertoire through which I express it. I hesitate to say that my art is different “post-pandemic,” since we very obviously aren’t post-pandemic, though we’re beginning to return to art-making that we think of as “normal.” I can’t even chalk all the changes up to lockdowns or periods of social distancing; isolation did more to fan the embers of changes already under way than they did to ignite new ones.

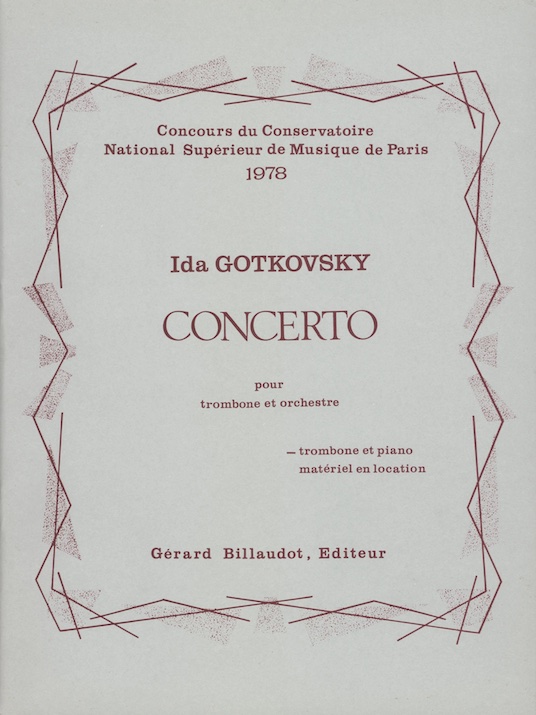

Understanding my search for new repertoire requires a certain knowledge of my backstory. I have two previous degrees in classical trombone, during which I performed repertoire in a variety of styles. To earn them, I gravitated toward programs that offered scholarships of experience, usually by playing in ensembles, and spent my time as most brass students do: taking ensemble assignments and playing what was programmed, churning through repertoire (standard and beyond) either to improve how I played it or to improve a specific technique, all the while obsessing over fundamentals. In the middle of it all I found some composers — Ida Gotkovsky, Gordon Jacob, Barbara York, Henri Tomasi, Rebecca Clarke, Elgar Howarth, Elizabeth Raum — whose music spoke to me beyond what was assigned for my technical and musical advancement. It was enough work to make the semesters fly by.

In many ways, in February of 2020 I was living a music graduate student’s dream.[1] I musicked as much as I wanted, enjoying full departmental support.[2] I was working as a research assistant, and so didn’t require a “day job” to make ends meet. I played, listened, and offered feedback in a supportive trombone studio. I looked forward to trombone choir every week. During a seminar in Irish Traditional Music, I sang in front of other people, in something other than an Aural Skills exam, for the first time since high school — and in Irish. I wrote pages of historical analysis each week for my musicology course in Englishness in music. I combed through hundreds of pages of nineteenth-century periodicals looking for concert and sheet music advertisements, explanatory details for footnotes, and confirmations of performance dates (separately, as my adviser’s research assistant and for my own thesis). When I look back at this now, in 2023, it’s easy to see how things rolled along as expected.

The next part of the story, by now, is familiar. Lockdown commenced. Musicians had to salvage what we could of our in-progress projects and start figuring out how to keep playing while facing the unknown. We logged on to Zoom to attend class, teach, and find the community we couldn’t have in person. But Zoom burnout is real, as we learned to our cost, and we had to find ways to fill the long hours between sessions when we would normally have been rehearsing or traveling. By April, during all those long days with no seminars or rehearsals to attend, I was actively looking for repertoire that was not only new to me to play but that expressed something new, as well.

I soon realized that I was specifically looking for new historical repertoire — “historical” as opposed to “contemporary,” music written in an idiom that was considered fashionable or contemporary in another specific time and place. Since my lockdown resources for practicing were limited — minimal soundproofing in my concrete, cinderblock apartment and limited patience for using a practice mute — I searched for nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pieces that would call for new kinds of expression instead of just riffs on the same standard forms, repertoire that would demand thinking through as well as physically playing through on the instrument. While I have great appreciation for both contemporary music and the composers who write it, I’m a historian. I have a historian’s love for understanding and interpreting musics in ways that are informed by their time and place while simultaneously speaking to a contemporary audience. I reasoned that, given this unprecedented amount of time before me, I had only to open enough scores or search enough libraries until that repertoire revealed itself.

What I found underwhelmed me.

Historical trombone repertoire is narrow, and overwhelmingly male, in every era and genre. As a result, most of it is also masculine-coded. Neither of these assessments surprised me; they were things I had known for so long that I probably took them for granted. Of the legions of gifts that my training in musicology has afforded me, some are the historical, philosophical, and political tools to find and understand the origins of my discontent with this repertoire, to put my finger on exactly why it stubbornly resists efforts to update it. Masculine-coding — in trombone repertoire and in others — is largely a product of late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century expressive norms in Western European art music, and though it’s rarely as straightforward as strong, individualistic, action-motivated, macho, thinking, intellectual = male and delicate, modest, feelings-motivated, reticent, embodied, emotional = female, such stereotyping is often visible and audible throughout. As musicologist Susan McClary describes in her now-classic volume Feminine Endings, classical music “presents a wide range of competing images and models of sexuality, some which seem to reinscribe [sic.] faithfully the often patriarchal and homophobic norms of the cultures in which they originated, and some of which resist or call these norms into question.” At the same time she acknowledges that, while there are no universal symbols for expressing these models, “usually some correlation exists among the images and attitudes toward sexuality manifested in the various arts at any given time.”[3] There are also hierarchies embedded in genre and style — for example, the privileging of “Absolute music” (i.e., music that only has meaning “on its own terms” instead of supporting an external narrative) as somehow the most serious kind of music because it identifies with the “pure mind” and denies the experiences and sensations of the body.[4] Thus in the trombone repertoire, as in most other solo repertoires, pieces like concertos are given pride of place in competitions, anthologies, and canons. Smaller genres like character pieces — often composed by women because these genres better fit their expected gender performance — are often relegated to the margins, seen as “filler” for recitals and recording projects.

Most of this coding and hierarchy is philosophical, stemming from Plato’s idea that music “for the mind only” is, by its very idealized contemplative nature, superior to music that serves a social function or is in any way rooted in the body (in his thinking, a “female” domain).[5] The gendering of Plato’s idealism isn’t a dusty idea that died with Plato but rather clung on to influence Enlightenment philosophy and, eventually, modern-era hierarchies of Western art music, wherein its significance runs deeper than whether a piece was composed by a man.[6] While pieces that adhere to these ideals promote ideals of the masculine as both superior (to anything else) and universal, an Other perspective — a woman’s, perhaps — is antithetical to its ideals.

Such coding has certainly never been unique to trombone or to brass repertoire, and some of it persists into the twenty-first century. It has also never prevented women from playing the available repertoire, but it limits their expressive capabilities. As such, contemporary composers, including women, continue to explore underused forms, unconventional techniques, new equipment, and other ways to expand the instrument’s creative boundaries.[7] But they don’t yet have the institutional inheritance of the “classical” repertoire. Ida Gotkovsky’s concerto from 1978 is probably the closest piece of historical “standard repertoire” by a woman that tenor trombonists have, and at the time of this writing she is still with us. Most players mentally limit her concerto to being “Paris Conservatory” repertoire instead of “standard” repertoire — a treatment that they predictably do not extend to similar pieces by Bozza or Tomasi.[8] Bass trombone repertoire has made some space for contemporary women composers — anyone keeping up with the International Trombone Association’s 2023 competition requirements will find movements from Raum’s Concerto for Bass Trombone listed for the first round of the George Roberts Bass Trombone Competition, among others — but the bass-specific repertoire is comparatively smaller and more recent than its tenor counterpart. In any case, these pieces are not yet considered “historical.”

Predictably, it’s not just the repertoire that’s coded, but the instrument and the social and political spaces in which it sounds. Both instrument and repertoire must be played by real people in physical spaces as components of musical institutions, and therein lies a built-in and persistent inegality. There remains a wealth of gender, race, and class problems in the low brass factions of classical music; disparities and inequalities of gender are particularly visible to me.[10] Reported cases of gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and assault in art music are not new news. Almost every gender-marginalized brass player I know has had it made clear to them through some event in their background that they were going to have to fight something to be included. Like so many of my female colleagues, I was not told where to apply, or advised to which old friends I should be sure to introduce myself. One of my earliest teachers did, however, make sure to tell me to “not let music school turn me into a lesbian.” I have had every off-color joke — from the merely dismissive to the sexually explicit — made to my face in a “professional” environment. An ensemble coach once told me that I was expected to be “quintet mom” in an otherwise-male ensemble.

There are too many instances of these kinds of treatment and worse to count, most notably Abbie Conant’s — a titan of the art of Playing Trombone While Female™.[11] To all of our satisfaction, Conant is a successful, supportive teacher and artistically fearless performer in spite of the obstacles placed in front of her. I’m happy to remain in the chorus of voices that says: the kind of treatment that Conant and others face has gone on longer than it ever should have. In the last ten years or so these experiences have become easier to talk about, and there are more communities of support for people who suffer through them, but we have a long way to go before the situation is tenable, let alone good. I can also be the latest person to tell the men in this field that they don’t just need to do better — they need to be better. Given the continued state of things, I’m not convinced that most of the men in this field are doing much more than performative listening. While there is a profusion of “diversity” rhetoric, and a handful of women artist-composers are enjoying professional success, it takes only a cursory scan through the lists of representative composers or the photos of orchestral, competition, and seminar personnel to see how homogeneous the power in brass sections remains.[12]

Such intransigence is perpetuating another less visible problem: the historical repertoire itself is complacent. New pieces aren’t perceived to have the cultural or intellectual cachet of the “standard” repertoire, though few will admit that it’s gatekeeping that prevents them from acquiring it. The older so-called “standard” stuff is still so ubiquitous that new work has to shout to be heard over it. Students must also learn to play the “standard” stuff in order to be considered accomplished in playing the instrument; by the time they reach “non-standard” contemporary repertoire, they can only experience and interpret it through the conventions of the “standard” material that they have internalized while learning to play. This isn’t unique to trombone or to brass repertoire but applies almost everywhere in Western art music.[13] In a world where “professional” is often synonymous with a relentless self-aggrandizing hustle to market oneself and one’s art, throwing around playing “classic” or “standard” pieces, including some études, thus becomes the only accepted shorthand for measurable accomplishment — i.e., a pissing contest. We’re missing out on much that our field is capable of because we’re unwilling to question the familiar practices of art music, and continually return to venerate only a body of historical repertoire played in increasingly narrower terms of correctness and prestige.

I’m not calling for proverbially boxing-up the whole of the repertoire and starting with a clean slate. There are some classics in our repertoire that can be both artistically beautiful and pedagogically useful in the ears and minds of thoughtful students and teachers, and they are more than capable of expression that isn’t merely self-aggrandizing to the artist. (There is contemporary repertoire capable of this, too — witness Natalie Mannix’s Women Composer Database, cited above). As a historian, being able to play music that can tell me where I artistically come from is important in addition to having contemporary music that strives toward reflecting the diversity of the musicians that play it. Historical repertoire by women is pretty thin on the ground in the trombone repertoire, and it will remain that way until we can unearth some more. Even when we do, this is not a case of replacing one dominant repertoire with another. Representation is still a significant problem, but it’s a different problem than the limits of our expression in historical repertoire. Current modes of expression that form the foundation of so much of our early playing experience are so constipated, so caught-up in ideas of their own universality, that they force artists to mimic them regardless of positionality. As Dr. Noël Wan observes in her confrontation of the objectivity and authority in academic Western classical music, “I worry . . . that doing away with all notion of objectivity, in art and in society, creates a solipsistic free-for-all, in which we become so preoccupied with selfhood that we forget that each self is situated amongst others.” The masculine-coded artistic “self” that our repertoire presents has forgotten this, and thus bills itself as a universal experience. The repertoire is complacent because it is too preoccupied with the mythical selfhood of the now-dead men who created it — a selfhood that readily represents fewer and fewer of the people who render it audible. There’s plenty of space for objectivity, for historical authority in interpretation, and even for an expression of the individual self in our historic repertoire, but it must communicate to more of us and by more of us than it currently does.

What I’m interested in is an expansion of the expression(s) available to contemporary musicians, particularly from historically marginalized groups, into musical conversations with historical figures whose backgrounds may be wildly different from their own. This is a much murkier problem than how to represent more marginalized artists, though continued efforts to find their music and bring it into the known historical repertoire will help. How do you call for an interpretation of a repertoire that may well rely on radical re-imaginings of gender-coding and interpretation? Can I imagine playing Hindemith’s 1941 Sonata — a milestone piece for most students — without #girlbossing it? When I offer my listeners transcriptions from the string repertoire by Rebecca Clarke (viola) and Ethel Smyth (cello), can they hear it expressing Justice, Temperance, Courage, or Community instead of a novel female variant of a standard concerto form? At what point does the meaning of a piece of historical music transcend our understanding of the “composer’s intent” in a way that keeps it vital and expressive — relevant beyond its historicality?

To answer the question, I must enlist help from Literary Studies — which, thanks in part to my training in Musicology, is yet another field that informs my understanding of music, in concert with History, Gender & Women’s Studies, and Social Theory. Within the realm of Literary Studies, Roland Barthes posited the idea of the The Death of the Author in a 1967 essay by the same name. Barthes argues that we cannot rely on biographical facts or aspects of an author’s identity to completely understand what was meant in a given work (though they may be relevant). The author’s biases and experiences, their intentions and biography, while they contribute to the author’s perspective, cannot serve as a definitive “explanation” of the text. It rejects the idea of authorial intent; the author does not decide the meaning of the author’s work, because the responsibility of making meaning of it lies with the reader.

Barthes’s theory has, predictably, drawn criticism throughout its life. It offers a useful description of how musicians — trombonists, certainly, but plenty of others as well — have so often been trained to treat their own historical repertoire. We “interpret” it, as we must, within very strict parameters, so that the audience may engage in meaning-making of the composer’s work. What ought to happen in the process adds an extra step, because music requires more mediation than does a text — there are more bodies, more interpreters, required for the sound of the music to be produced and to reach the listener than are required for written ideas to reach the reader. The performer needs to do the same amount of meaning-making as the reader would do of a text, if not more; the listener then makes meaning of both the piece that the performer has chosen and of the performer’s meaning. To return to Dr. Wan’s concern that doing away with objectivity in music would lead to solipsism, this triangular relationship makes a solipsistic interpretation far less possible because what’s being performed is a conversation between the composer, the performer, and the listener instead of a unilateral interpretation by the performer of the composer’s work for the listener’s consumption.

This pushes me to a further question: if it’s a conversation, then what are we talking about? Here is where the performance of classical Western art music becomes a living practice, where ideas like Justice or Temperance (or Euphoria, or Revenge) come in, because they’re the substance of the conversation. In brief, I am asking my audience to accept, and indeed to celebrate, an artistry where I am not merely a signifier of the repertoire I’m playing — “a contender” because I play Tomasi or Dutilleux, “serious” because I play Brahms or Wagner, or “feminist” because I play Gotkovsky, Clarke, or Smyth — but one where I am considered equally human as an interpreter.

Such an approach to historical repertoire feels refreshingly authentic to me — not in the way that the term has often been used historically, which is an erroneous combination of “as the composer intended” and “fresh from a time capsule,” but as Richard Taruskin described it when he wrote that:

Authenticity . . . is more than just saying what you mean. That is mere sincerity, what Stravinsky called ‘a sine qua non that at the same time guarantees nothing.’ It carries little or no moral weight. . . Authenticity, on the other, is knowing what you mean and whence comes that knowledge. [It is] knowing what you are and acting in accordance with that knowledge.[14]

Like Barthes, Taruskin has drawn plenty of criticism for his work. I’m invoking his description specifically because it strikes the balance of sincerity and historical weight that I’m looking for. “Authentic to the performer” in this case is not only what the performer thinks and means. That would be the sincerity that Taruskin describes; it’s important, certainly, but it’s not the limit of expression. Knowing “whence comes that knowledge” of what you mean speaks to the conversation that I’m striving for. Perhaps predictably — or perhaps not — it’s the kind of conversation that brings Barthes and Taruskin (et. al.) together in my thinking in the first place.

This scholarly rabbit hole on musical authenticity runs deep. I’m pausing near the entrance only because questions of authenticity so often follow questions of historical interpretation. As Taruskin, Leech-Wilkinson, Temperley, and Winter all attest in the same article (1984), our interpretations of historical musics reflect the historical moments of those interpretations far more than they reflect their supposed “original” versions. I’m not in the business of debating the nature of authenticity — thus why I’m allowing Taruskin, Temperley, and others to do the heavy lifting here for me — but rather of questioning who authenticity represents and how musicians can expand it to include more musical interpreters. This vitality and expressivity, this relevance that has respect for but not deference to historicality, this way of “reading” and interpreting historical musics that does not call for the Death of the Composer but puts them in conversation with interpreters and listeners — let this be what speaks to future historians about how we understand and value our historical music.

I’m not really asking about capability when I ask if it’s possible to imagine these things. I want to know if such interpretation can be comprehensible to an audience steeped in the traditional meanings and trappings of this repertoire — meanings that often reflect broader trends in academic Western classical music — without foot-long program notes.

While considering what an aesthetic expansion of our repertoire might sound like, I have often remembered writing by Judy Chicago: “One might argue that the 1970s feminist art movement represented [a] moment when female artists began to realize that the form of art itself would have to be different if it was to communicate a female-centered point of view” — an idea previously espoused by Virginia Woolf.[15] I would expand this to say that the form of our art will need to change if it’s going to be able to express the points of view of artists who are not men with the same depth and breadth that it expresses the points of view of artists who are men — but also if it’s going to be able to express the complexities and relationships of the community of artists it represents. No artist, however isolated, works in a vacuum. At the same time, changing the form of our art cannot be the exclusive responsibility of contemporary repertoire. As an artist who plays historical music, I cannot and should not be limited to the forms of expression available from composers who overlap with my own identity groups, nor should I have to emotionally cosplay as a nineteenth-century man in order to have such an expressive relationship with “standard” repertoire.

Somewhere in the middle of all of this I became a musicologist-who-performs instead of a performer-who-spends-overmuch-time-in-the-library, and by the time isolation and lockdown restrictions began to ease, it was effectively impossible for me to return to my artistic “business as usual.” I’m now near the end of my Ph.D. coursework and preparing to conduct extended research in archives overseas, which necessitates honing the skills that made re-evaluating my relationship with historic repertoire possible in the first place. For the first time in almost ten years, I am taking a conscious and chosen rest from the instrument — to think, to write, to listen, and to imagine what my future musicking might look like. It’s a grand understatement to say that expressing more expansive ideas, moving away from self-aggrandizement, and changing the very form of our art — from that of the individual producing music for consumption to one of a conversation between individuals interpreting music for each other — all have the potential to change the shape of our field. These pursuits have the potential to renew it, to utterly transform it into something sustainable, multi-faceted, and expressive for everyone who participates. We ignore the potential of this transformation at our peril.

[1] In February 2020 I was nearly finished with the master’s degree portion of my master’s/Ph.D. combo program in musicology at the University of Illinois. At the time of this writing, my Ph.D coursework is nearing completion and I am preparing materials for my dissertation.

[2] Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1998): 9. Small writes: “To music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing.”

[3] Susan McClary, “Sexual Politics in Classical Music,” in Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1991): 54–55, fn. 184. In her footnote, McClary offers a list of studies that expand on the changes in constructions of gender and sexuality that she describes in the text. Nearly thirty-two years later, there are even more.

[4] McClary, 54–55.

[5] Regelski, Thomas A. “Music Appreciation as Praxis.” Music Education Research 8:2 (2006): 281–310. In addition to providing terminology, Regelski discusses the philosophical influence of Plato on the internal hierarchies of Western art music that persist into the twenty-first century.

[6] Regelski, 289.

[7] Natalie Mannix has been particularly vigilant in her work to collect and maintain a list — titled the Women Composer Database — of compositions by women composers for trombone in various solo and ensemble configurations. The International Women’s Brass Conference (IWBC) also maintains a Historical Brass Archive that works to keep as many records as possible of women brass musicians, including composers, available.

[8] The low number of recordings of Gotkovsky’s concerto and its lack of appearance on lists of required repertoire for competitions make a strong suggestion, at best, that she’s being excluded. One difficulty of tracking instances of the existence and use of historical repertoire is that a lot of the projects that are keeping lists of women writing music for trombone aren’t consistently dating their repertoire in these records. The Mannix Women Composer Database that I cite has a long list of materials, but no indications of how old they are. Most of the composers on the list are contemporary.

For a thorough account of the construction of classical trombone repertoire during the nineteenth century (including, but not limited to, the Paris Conservatory repertoire), see Guion, David M. The History of The Trombone (Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press, 2010): 133–185.

[9] It is worth noting that, of the twenty-nine composer names listed on the list of 2023 ITA Competition Repertoire, four of them are women (Elizabeth Raum, Daniela Candillari, Amy Mills, and Carrie Magin) and all of them are contemporary. Of these, Raum’s, Candillari’s, and Magin’s pieces are all for bass trombone and Mills’s is for trombone quartet.

[10] In this essay, most of my examples come from women — my own identity group — though many of the issues and experiences apply across groups of gender-marginalized people.

[11] For accounts of Conant’s eleven-year struggle to play in the Munich Philharmonic, for which she had won an audition in 1980, see her website; Brenda Parkerson’s 1994 documentary, “A Solo Among Men”; William Osborne’s “You Sound Like a Ladies’ Orchestra” (Conant’s husband); and the final chapter of Malcolm Galdwell’s Blink.

[12] One regular and vocal critic of this state of representation, both in brass sections and others, is Katherine Needleman. She/They is an oboist and activist for gender and racial representation in classical music, and regularly reports on the under-representation of minorities in orchestral instrument sections.

[13] As with my previous acknowledgment of how visible gendered issues of trombone playing are to me (fn 10), I similarly acknowledge that I’m calling for this expansion of expression from a trombonist’s perspective. This is certainly not limited to trombonists or to low brass repertoire.

[14] Taruskin, Richard, Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, Nicholas Temperley, and Robert Winter. “The Limits of Authenticity: A Discussion.” Early Music 12, no. 1 (1984): 3.

[15] Judy Chicago, The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2021), 90–1.