The past carries with it a secret index by which it is referred to redemption.

Walter Benjamin

In this, our second Editors’ Corner, we recommend a few artistic works, old and new, for your perusal. Considering this issue’s emerging theme of shifting vantage points, and the contentious holiday season in which we are publishing this, we found ourselves meditating on what it means to see things from new perspectives, and on the process of transformation from old to new — of drawing into question (with measured empathy) what was and moving thoughtfully (however gently or violently) toward what could be. We hope you enjoy tracing these themes throughout the Corner, throughout the articles in this issue, and throughout the magnificent, ceaselessly changing life we share.

Enjoy!

READ

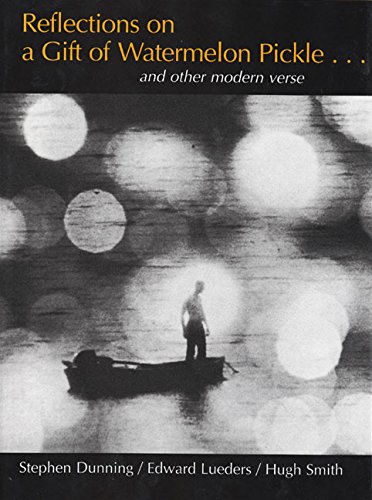

Reflections on a Gift of Watermelon Pickle… and Other Modern Verse (1966)

From the title alone, you can imagine my delight when I came across this book in a used bookstore in Georgetown, TX last summer. And, besides my affinity for volumes of poetry — for thoughtful compilations of any kind, really (hence, The Collective) — even more engaging is that at the time of its publication in 1966, this volume was a revolutionary high-school level poetry textbook. The structure and style was conceptualized by compilers Stephen Dunning, Edward Lueders, and Hugh Smith as an antidote to the stale, stiff, and stiflingly packed texts to which students are often subjected, and the poems were crowd-sourced and student-adjudicated from a staggering 1,200 down to the 114 that appear in the book’s final version.

I love the anthology’s premise, not only for its learner-centered pedagogical approach but because the compilers explicitly encourage learners to think, to learn, to move slowly and critically. In the volume’s introductory note, they write: “Give every poem a chance to speak to you. Reread. Read aloud. Make your ears work on each poem. Expect to find surprises—then read slowly enough to enjoy them” (emphasis mine). Organized into 15 themed sections followed by a series of reflection questions, the book’s contents truly range from the sublime to the ridiculous.

My favorite, and the one most akin to this issue of The Collective, is this short poem by John Moffitt that speaks to how we can learn to see things from the perspective of another:

To Look at Any Thing

To look at any thing,

If you would know that thing,

You must look at it long:

To look at this green and say

‘I have seen spring in these

Woods,’ will not do—you must

Be the thing you see:

You must be the dark snakes of

Stems and ferny plumes of leaves,

You must enter in

To the small silences between

The leaves,

You must take your time

And touch the very peace

They issue from.

John Moffitt

All that said, however truly progressive and revolutionary it was in the 1960s, the anthology is still a product of its time. As bemoaned by second edition contributor Naomi Shihab Nye, the first book is “very white and very male.” And while the second iteration did not reach the level of acclaim of the first, the reimagining did manage to draw a more diverse poet base. Nye is quoted in this fantastic Poetry Foundation write-up about Watermelon Pickle: “We were also in the slightly unsavory business of kicking out poems. Poems we felt were not appropriate in the expanding-consciousness culture, and that maybe didn’t ring right to us.”

Though I haven’t been able to get my hands on the 1995 version, I imagine poems like John Fandel’s “Indians” may not have made the cut. Whatever poetic value it might possess in its wordsmithing, this poem represents fundamental problems in the way that some white Americans think — dream, even — about indigenous populations: totally essentialized to cultural tropes, total lack of specificity (i.e., all Indians are just Indians, rather than specific tribes with specific identities), and, perhaps worst of all, the widespread misconception that Native Americans no longer live on this land — or, rather, the denial that they still do.

This is not to say that we should shut our eyes and ears to Fandel’s poem, but that perhaps, instead, we should turn our rapt attention to the writings of living indigenous writers. . .

The Sixth World series, by Rebecca Roanhorse (1996)

Trail of Lightning and Storm of Locusts are the first two books in award-winning author Rebecca Roanhorse’s post-apocalyptic fantasy series The Sixth World (third book forthcoming!). The books are set in Dinétah, the homeland of the Navajo people, after the climate apocalypse has drowned most of the world and Dinétah has been reborn; they follow Maggie Hoskie, monster hunter and supernaturally gifted assassin, and her assortment of misfit friends and sidekicks as they track living legends and large-scale witchcraft to survive — and to keep each othre safe — in a dangerous, deteriorating world.

Through Roanhorse’s thrilling storytelling, weaving of indigenous lore, and critical approach to U.S. history and to the urgent future of our planet, readers are able to consider the world through a Native lens. Roanhorse doesn’t stop at the reality that indigenous groups are very much still here, but fleshes out a future in which Native peoples will remain on this land after all else is gone. Her fiction argues, specifically, the cruciality of indigenous imagination and, more broadly, the power of collective history and myth to shape human understanding of past, present, and future.

Put simply, and in alignment with this issue, good fiction is an invaluable aid in the process of really trying to “look at a thing,” to “be the thing we see.” And Roanhoarse’s fiction is good fiction.

Plus — what better time of year to critically consider, and to celebrate, indigenous life?

WATCH

Art is Dead by Bo Burnham — 2014 performance in the Green Room

Alright. Take a break from reading, and watch young Bo Burnham’s sardonic meditation on the role of art in society and the catch-22 in which artists find themselves:

This gets at an issue that we at The Collective take to heart: When art is made for its own sake, it’s not consumed by the masses; but once an artist’s work is picked up and pushed out on a global scale to create profit, is it really art? How can one stay a “pure artist” in the corporate system, when total commodification is the end result of “success”? It’s clear that this a quandary with which Bo Burnham struggles, and in the most self-deprecating and humorous way.

If you hadn’t seen this video, you’ve probably seen (or at least heard about) Burnham’s most recent musical comedy special and pivotal work of pandemic genius Inside. Although he has taken some criticism for it — we get it, many don’t want to hear a rich white man talking about social change — we find his systemic critique blunt, true, and artfully crafted. Plus, his songs are incredibly catchy and exhibit a fine musical creative mind. Besides, in the spirit of this Collective issue, Burnham is a master of shifting perspectives, using genre variety, socks puppets, and even the work of other artists to make large- and small-scale social critiques.

The point is, we’d rather have Burnham’s ideas out in the world than not — his work is exactly the kind of thing we believe artists should be doing now: taking risks; rejecting systematically-bound ideas about art; and melding genres, disciplines, and personal style all to build a social reality that prizes critical and artistic thinking.

LISTEN

Beautiful Mechanical (2011) and Ecstatic Science (2020) by yMusic

I first heard yMusic in 2011 on a routine car trip. Though classical music is usually playing on my radio, their track immediately drew my focused attention. A lone clarinet sang out a simple but evocative call that was soon joined by some strings, a flute, and then about thirty seconds in, I thought incredulously, “Is that a trumpet?? What kind of ensemble is this?” For the entirety of the ten-minute piece, I was completely aurally enthralled with the delightful motivic patterns, surprising rhythmic turns, beautiful harmonies, and seamless blend of the ensemble. So much so that, when I arrived at my destination, I just sat in the car to ensure I heard the identity of this new composition that was performed so magically. It was “Clearing, Dawn, Dance” by Judd Greenstein, performed by yMusic on their debut album Beautiful Mechanical (2011). Since then, they have recorded three more full-length albums, Ecstatic Science (2020) being the most recent, with another one on the way.

The instrumentation of the sextet (violin, viola, cello, flute, clarinet, and trumpet) is one of its most unique attributes and certainly caught my attention in the car that day. And the group has collaborated with scads of contemporary composers to premiere new works for their instrumentation. But what is most impressive to me is the new and distinct sound they have created that they deliver on every piece. Their music is fresh, accessible, and unafraid to cross genre boundaries. In fact, their distinguishable style and approach to classical music has led to collaborative opportunities with many of the most high-profile popular musicians of our time, including Paul Simon, Ben Folds, and Regina Spektor. Not only that, but each of the members is multi-talented and pursues a variety of artistic interests and projects. For example, the flutist Alex Sopp is also a visual artist, and her work includes album artwork for yMusic and other performers.

While it’s worth acknowledging that not everyone has the privilege of their resources or pedigrees, this ensemble’s work is undeniably an exciting and valuable direction for classical music. In short, yMusic has taken the traditional classical music paradigm and revitalized it in every way imaginable — through instrumentation, selection of works, performance venues, cross-genre work, and collaborations.

We leave you this time with words of advice from Eve Merriam, whose “How to Eat a Poem” sets the stage for the delicious pedagogical landscape of Watermelon Pickle.

How to Eat a Poem

Don’t be polite.

Bite in.

Pick it up with your fingers and lick the juice that

may run down your chin.

It is ready and ripe now, whenever you are.

You do not need a knife or fork or spoon

or plate or napkin or tablecloth.

For there is no core

or stem

or rind

or pit

or seed

or skin

to throw away.

Eve Merriam

Thank you for joining us in our Corner, and for reading The Collective’s second issue! We hope you will take your sweet time with each of these delectable articles, devouring, savoring, and digesting them as they deserve to be — after all, they are “ready and ripe now, whenever you are.”

Articles in this issue:

- Featured Article: Learning Pedagogy, objectivity, and positionality: Renegade thoughts from a classical musician by Nöel Wan

- Bridges An expectation of silence: The classical music conundrum by Vijay M. Rajan

- Diversity Race, identity, and music: How artists of color reconcile imposter syndrome in an ever-changing industry by Brandon K. Smith

- Ethics Thinking like an artist by Mona Sangesland

- Movement Of bath bombs and dentists by Ian Nutting

- Nugget November 2021: Inclusivity in Pedagogy by Contributing Writers