In the spirit of springtime, The Collective’s fourth issue addresses rebirth on several levels: through psychological alteration — how we question, investigate, and radically embrace or reject core values; via physical movement — how we redefine ourselves by leaving home or by shifting through space in some new way; and in literal death — how beings are reincarnated, made into ghosts, even lost altogether, and how we choose to live with that, individually and collectively. Relatedly, in light of the war in Ukraine (which, thrust into our collective consciousness via social and news media, should also be an unsettling reminder of all the other global humanitarian crises not making it to our news feeds), this Corner encourages readers to consider art and artists in the time of war, and to critically assess the artist’s role in resistance, resilience, and rebuilding.

In many ways, this issue questions the value of artmaking at life’s pressure points. What happens when the world we know — visible or not — explodes before us? Maybe art can’t literally save our lives, but at least the process of making art forces us to live thoughtfully. And the willingness to be thoughtfully alive — not at all discrete from the courage and softness it takes to be thoughtful about death — is what can truly awaken and renew us.

As you absorb these themes through this issue, may the many ideas and recommendations take root and bloom through your own processes of renewal and revitalization.

READ

Steven Galloway — The Cellist of Sarajevo (2008)

It screamed downward, splitting the air and sky without effort. A target expanded in size, brought into focus by time and velocity. There was a moment before impact that was the last instant of things as they were. Then the visible world exploded.

In 1945, an Italian musicologist found four bars of a sonata’s bass line in the remnants of the firebombed Dresden Music Library. He believed these notes were the work of the seventeenth-century Venetian composer Tomaso Albinoni, and spent the next twelve years reconstructing a larger piece from the charred manuscript fragment. The resulting composition, known as Albinoni’s Adagio, bears little resemblance to most of Albinoni’s work and is considered fraudulent by most scholars. But even those who doubt its authenticity have difficulty denying the Adagio’s beauty. Nearly half a century later, it’s this contradiction that appeals to the cellist. That something could be almost erased from existence in the landscape of a ruined city, and then rebuilt until it is new and worthwhile, gives him hope. A hope that, now, is one of a limited number of things remaining for the besieged citizens of Sarajevo and that, for many, dwindles each day.

Steven Galloway (pp. xv-xvi)

Galloway’s beautiful prose transpires from four points of view: the principal cellist of the Sarajevo Symphony Orchestra, a young female sniper, a forty-year old man with a wife and children, and a man in his sixties whose wife and son have escaped to Italy. Though fictional, the work is based on the Siege of Sarajevo (April 5, 1992, to February 29, 1996) and inspired by the actions of the real cellist Vedran Smailovic who, after twenty-two innocent people were killed in mortar attacks while buying bread at the markets in Vase Misinka, played Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor for the next twenty-two days at the location of the attack in an active war zone. Many came to listen, some every single day.

The novel questions what it is to be human in a time of war, a human making art in a time of war, and how the people of Sarajevo had become living ghosts — ghosts to the world (foreign powers turn a blind eye), ghosts to each other (they do not recognize their friends as they did before, in look or in demeanor), and ghosts to themselves (they are not like their past selves; they are full of fear, of hate, of animal impulses). The cellist’s performances allow the citizens of Sarajevo to see themselves again (his shoes shine “like mirrors”), to recognize what makes them human, what makes them alive. The cellist preserves his humanity by sharing his music; the people, in turn, are given hope that their acts of humanity matter in an aggrieved and forgotten city, and they are made alive again.

The graphic design of the book itself is even ghostly. The names of the four characters head each chapter in light text, and when a chapter is written in one particular perspective, that name is printed in boldface black to stand out against its gray, ghostly neighbors. Interestingly, the cellist’s perspective is only the very first section, so his name remains a ghostly presence throughout the book. The book is also separated into five parts, with each given a separate title page. The first title page is white text on a black page, but each subsequent one is lighter and lighter until part “four” is white text on a page so light gray it is almost white. The reader might fear the characters will disappear altogether.

One of our favorite passages (below) is from the point of view of the sniper, Arrow, before the war, and it gorgeously renders the ghost of her previous life:

Ten years ago, when she was eighteen and was not called Arrow, she borrowed her father’s car and drove to the countryside to visit friends. It was a bright clear day, and the car felt alive to her, as though the way she and the car moved together was a sort of destiny, and everything was happening exactly as it ought to. As she rounded a corner one of her favorite songs came on the radio, and sunlight filtered through the trees the way it does with lace curtains, reminding her of her grandmother, and tears began to slide down her cheeks. Not for her grandmother, who was then still very much among the living, but because she felt an enveloping happiness to be alive, a joy made stronger by the certainty that someday it would all come to an end. It overwhelmed her, made her pull the car to the side of the road. Afterward she felt a little foolish, and never spoke to anyone about it.

Now, however, she knows she wasn’t being foolish. She realizes that for no particular reason she stumbled into the core of what it is to be human. It’s a rare gift to understand that your life is wondrous, and that it won’t last forever.

Steven Galloway (p. 5)

Likely owing to such striking passages as this one, the book has garnered the accolade of “universal” story, even printed in the blurb on the book’s cover. Though the novel does indeed sublimely depict ineffable qualities of human existence, we would critique the choice to use “universal” as a tool to reach an audience reluctant to engage in content about faraway conflicts. The danger of calling war stories universal is that it perpetuates uncritical and ethnocentrically privileged ways of thinking, seems to accept war as natural or just “part of life,” and denies both the nuances of uniquely situated local experiences and the complex geopolitical power relations that created them.

However, as audiences who may not want to engage with all the problems of the world unless we are told they are directly relevant to us, perhaps we can question why we seek the label of universality in the first place. As the novel so artfully questions about our human existence: what does it mean to rebuild a city, a family, a life? And what role does art play in ensuring our humanity endures?

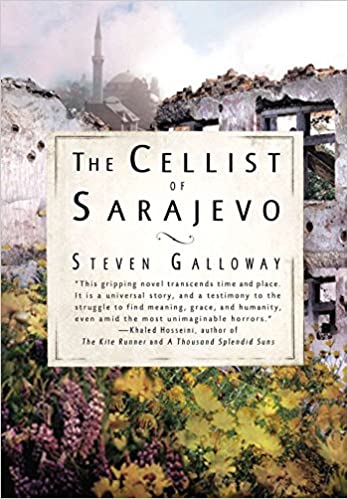

WATCH

Peter Cattaneo — Military Wives (2019)

Military Wives (2019), directed by Peter Cattaneo, is a comedy-drama based on the true story of a choir formed at an English military base by women waiting for their partners to return home from Afghanistan. The film is equally armed with humor and pathos, and surprised us with how moving it was to watch and hear these musically “untrained” women sing to cope with pain, grief, confusion, isolation, and even boredom. One particular guffaw-worthy moment occurs when the choir begins to rehearse Tears for Fears’ 1985 pop hit “Shout.” A few women indeed “shout” out the notes rather than sing them, as they suddenly realize how liberating it is to release their pent-up emotions through their own instruments. This “unmusicality” also serves as a point of contention between the two leads: the Colonel’s wife (Kristin Scott Thomas), who wants everyone to perform with absolute perfect pitch and in the revered classical style, and the newly-appointed Sergeant Major’s wife (Sharon Horgan), who is more intent on giving the women something constructive and meaningful to do together. The film grapples with these two sides of art-making, questioning “Who is it for?,” “Why should we do it?,” and “Is it less meaningful if it doesn’t reach a certain objective standard of quality?”

The film does not engage in much critique about the war or the military as a social-political construct. The most perspicacious comment is spoken by Horgan’s character as the military wives ignore a protestor at the market: “We don’t have the privilege of being against the war; we’re married to it.” Though the movie doesn’t focus on these issues, the viewer will find some interesting hierarchical and gender politics to discuss; it’s hard to deny the choir’s psychological and communal benefits in the women’s lives, but the structures that made the choir necessary in the first place, and that facilitated its formation and promotion, remain worth questioning. Ultimately, however, Military Wives is a “feel-good” movie, reminding us what it means to make art together in a time of grief, and how that can help us emerge anew — whether the art is “perfect” or not.

LISTEN

“Ukrainian musicians and artists respond to the war in many different ways”

This short episode of NPR’s State of Ukraine podcast highlights the voices and contributions of Ukrainian artists in war relief efforts. This accessible and beautifully reported seven-minute listen features interviews with artists and samples of their music, and does not postulate a one-size-fits-all approach to artists-as-activists. Mainstream media is not always the best starting place for critical cultural awareness, but coverage like this allows us to hear from Ukrainian artists directly and to cut through the noise and the bandwagon activism that can tend toward the uncritical. Most broadly, it encourages us to consider the variety of ways in which artists respond to war, both through and beyond their art.

To further encourage you down the rabbit hole of Ukrainian music and culture, we’re accompanying this recording with several interesting artists and projects for your listening perusal, through the lens of two art centers in Ukrainian cities, drawing from mainstream media sources and popular music.

A tale of two cities’ centers

In Lviv, Ukraine, the Lviv Municipal Art Center has been transformed into a refuge for those fleeing violence in Ukraine to find rest, food, community, mental health resources, and more. In this broadcast from CBC/Radio-Canada, Lyana Mytsko (the Center’s director) speaks about their work and gives a video tour of the gallery transformed into a shelter. It’s amazing that, in this case, the artists and the space they have cultivated — rather than the art itself — is able to offer material transformation and relief.

In Kyiv, Ukraine, the independent theater Dakh Contemporary Arts Center is home to several contemporary ensembles creating innovative Ukrainian music and politically-oriented content demonstrating Ukraine’s complex geopolitical situation and contemporary responses to long-term tensions with Russia. For an edgy bop protesting the annexation of Crimea in 2014, check out this live performance of “To Moye More” (“That’s my sea”), complete with rubber duckies and interpretive dance, by the “freak cabaret” group Dakh Daughers (we especially appreciate the lead singer’s aside at 2:27, which ends (in English): “We want to build a new world without war, because war is terrible, because war is shit! I’m sorry, but, excuse me, YEAH!”).

This song is featured in a lovely write-up by Ukrainian-American writer and journalist Natalia Antonova about “new femininity” in Ukrainian music.

And, finally, something a bit more lighthearted: we thoroughly enjoyed this NPR Tiny Desk Concert with the self-proclaimed “ethnic chaos” band DakhaBrakha, meaning “give/take” in old Ukrainian. Currently on tour in France, DakhaBrakha has left this message on their website homepage expressing their approach to the current crisis:

We believe in international support, and most of all, in the Ukrainian army! It is clear that in such circumstances we are canceling the upcoming concerts in Ukraine, but hoping to play them in the near future. But we will play concerts throughout the world to support Ukraine and raise money. We will win! Glory to Ukraine!

Parting thoughts

The release of this issue is also a poignant time to recall the quote that informed our founding, as it addresses war, growth, and the power of art to create change.

Is art resistance? Can you plant a garden to stop a war? It depends how you think about time. It depends what you think a seed does, if it’s tossed into fertile soil. But it seems to me that whatever else you do, it’s worth tending to paradise, however you define it and wherever it arises.

Olivia Laing, re: Derek Jarman

And in the spirit of critical thinking and intentionality of language, we juxtapose this with a quote often shared haphazardly by artists on the internet during man-made global crises:

This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.

Leonard Bernstein

For all its possible good intentions, this may just encourage musicians to believe they can, as one critic says, “transform art’s political impact by doing what they’re already doing—only better” (the irony here does not escape us, we know how Bernstein felt about critics). Absolutely, art(making) can provide invaluable comfort and relief in difficult times. That matters. But art’s efficacy to create material systemic change should be questioned such that we seek to create more effectively. It’s not enough to keep our heads down, do what we’ve always done, and perpetuate the assumption that our work has everlasting inherent good. In the pursuit of a better world, both life and art can and should make us uncomfortable. In order to grow, we must be willing to engage fully in this process — to plant and tend new seeds, to think about time differently, to question. However, wherever.

Articles in this issue:

- Featured Article: Politics Representation is not enough by Vijay M. Rajan

- Bridges The ghost in the house by Nöel Wan

- Diversity If a dragon dies in the forest, do humans hear a sound? by Putu Tangkas Adi Hiranmayena

- Ethics This essay is not perfect: Confessions of a lapsed perfectionist by Brandon Smith

- Movement Lifelines in a year of “Why not?” by Ann Moss

- Performing World-building is a real-time performance by Ian Nutting

- Politics Representation is not enough by Vijay M. Rajan

- Nugget March 2022: Media Mélange by Contributing Writers