Time is the essential piece of interpretation.

Lydia Tár in Tár

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

The past is not the least bit abstract, it is made up of very concrete, small things.

Georgi Gospodinov, Time Shelter

While all Collective articles engage with source material in some way, this issue is unique in that each article takes one or more sources as its base — from codified art forms like films, books, poems, and music to more quotidian things like social media, laundry, and the environments we live in. In a way, they are all response pieces, taking materials, things, stuff not as means to some other end but almost as ends in themselves, as objects worthy of reflection in their own right, as concrete, small things that carry their own histories and futures and that inevitably impact ours.

The modal and methodological shift brought by this issue has us reflecting on the relationship we (artists, humans) have with “source material” (artistic, otherwise) — how we engage such materials in our own interpretation and meaning-making, how through this process we inevitably enter into a relationship with the material’s creator. It’s natural if not normal for us to bring our own interpretive and creative nuance to this, to be in the business of interpretation and representation as much as creators are in the business of intention, to vision and re-vision throughout time. The important thing, as artists and humans living and thinking artistically, is to take the time to revision sensitively, to be responsible in our engagement with the lineage and intention of materials, and to bring meaning and nuance to our part of the conversation.

We invite you to do the same as you read the articles in this issue and the recommendations we offer in this Corner, three works that critically address the meaningful incorporation of and interaction with source material.

READ

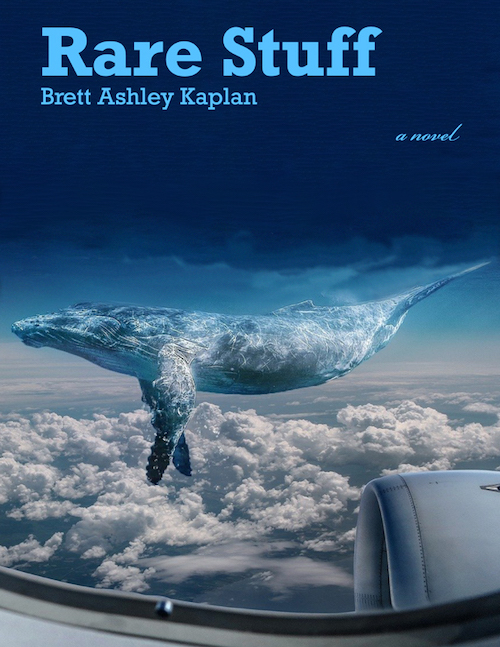

Brett Ashley Kaplan — Rare Stuff (2022)

In her first work of fiction, a novel unconventionally developed and undeniably “dreamy,” Brett Ashley Kaplan pays tribute to the tetheredness of everything, the urgency of care, and the critical role of stuff in our lives. Riveting, personal, and sprawlingly important, Rare Stuff is a poignant warning about the perils of our planet’s trajectory that deserves the captive attention of all those interested in a better world.

Kaplan’s storytelling alternates amongst the first-person perspectives of Sid (following the death of her father, Aaron) and André (Sid’s “long-suffering” Guadeloupean boyfriend) as well as segments of Aaron’s unfinished fiction manuscript, inspired by the work and dreams of Sid’s long-lost cetologist mother, Dorothy. Soon after releasing Aaron’s ashes into Lake Michigan, Sid discovers her father has left her a suitcase full of “rare stuff” — a single red high-heeled shoe, a miniature sculpture, a photograph, and so on — leading her on a quest to find her mother. Against an ethereal backdrop of unraveling mystery, ecological fantasy fiction, and the ever-presence (and ever-inseparability) of grief and love, Sid and André follow the trail(s) of Aaron and Dorothy, peeling back dizzying layers of truth and identity to face the visceral, vital, material complexity of ancestral lineage and (re)discovering one another in the process.

In the spirit of this issue’s theme, it’s worth noting how intricately stitched together is source material in this book. Kaplan lovingly cultivates each character’s rich intellectual reality and creative pursuits, the inevitable linkage of which affords depth, flow, and poeticism within and between characters. Aaron is a novelist, and André a literary scholar; both are interested in Melville (inextricable, of course, from Dorothy’s love of whales). Sid is a photographer documenting interracial love, a category we see her working out in the darkroom, in Aaron’s novels, and in her own relationship with André. Sid’s family is Jewish, as is André’s, and the book’s language seamlessly interweaves Yiddish terms and references to Jewish life around the globe; this includes the whales in Aaron’s novel using Yiddish to communicate with humans — yes, the whales speak Yiddish, a selection they made in the early 1900s when Yiddish was “an international language with a widely distributed press” (p. 98). Kaplan also prizes black voices in her characters’ thinking, quoting writers like bell hooks, Toni Morrison, Lucille Clifton, and C.L.R. James. And even as the novel’s alternating perspectives shape the text in chapter- or part-like chunks, Kaplan enfolds excerpts from letters, interviews, journal entries, book reviews, and other sources so that her characters can emerge multidimensionally, as humans do, in amongst the things that give our lives meaning, direction, and context. Like Aaron’s fictional lead, Solange, and her whale companions, Kaplan’s characters are all swimming together, in glass rooms, with their intertwined histories and the significant stuff (recalling Gospodinov’s “concrete, small things”) that bring them to life.

Embodied in the (doubly) fictional villain from Aaron’s manuscript, energy tycoon Drake Barents, Rare Stuff centers the historicity of human hate as its key antagonist. “Hate is very, very old,” Sid remembers Aaron saying to her, in childhood. “Nearly every day—about 200 per year—species go extinct. We don’t care for our planet as we should. And humans do not care for other humans as we should” (p. 55). With striking clarity, Kaplan’s story links the tragedies of ecological destruction, racial discrimination, and genocide (Jewish life, black life, whale life), and throughout the novel, Kaplan sets forth the “through line between discriminations,” arguing (via Aaron, via André) that “we’d be foolish to make everything too discrete—that would be far too tidy for the chaos of the universe, the planet” (p. 126). Just as human injustices are chaotically bound, however, so, too, is everything else; so, too, are we. Kaplan urges that our cultures — humans and whales, humans and humans, etc. — might be more alike than we think, and that it is in connecting with and caring for one another that we can overcome the enduring but not immortal criminality of hatred.

While Rare Stuff‘s critical perspective and impressive synthesis of source material and history are surely informed by Kaplan’s years of academic publishing, teaching comparative and world literature, and directing the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, Memory Studies and at the University of Illinois, it’s clear that the book is a work of heart even beyond Kaplan’s professorial work. If you make the wise choice to read this book, I highly recommend spending time with Kaplan’s “Acknowledgments” following the novel’s close — a tender testament to connectivity and interdependence, to the love Kaplan brings to this book, and to the tangible hope she holds for a more nurtured, nurturing world.

WATCH

Todd Field — Tár (2022)

Anyone coming to the film Tár hoping to see a detailed depiction of a powerful figure falling to cancel culture will be disappointed. In fact, upon initially viewing the film, we both felt the story didn’t deliver on its promise. However, after long discussions and weeks of mulling over all the details, we came to another reading — that writer/director Todd Field is telling a very different story altogether.

Throughout the film, Field peels back the layers of fictional conductor Lydia Tár. While the setting of classical music and her intention to record Mahler’s fifth symphony are extremely prominent in the first half, they are increasingly stripped over time, becoming almost irrelevant as the film progresses. As these layers are sloughed away, the true main idea of the movie presents itself: the mistaken conflation of identity and intent — eliding surface-level labeling identifiers with the actual actions and behaviors.

Classical music is chosen as the setting only because it provides a powerful metaphor for how an audience or performer/conductor makes meaning out of a composer’s intent, filtered through their own identity. And the relationship between classical music and the blinding nature of elitism makes the setting useful.

At the beginning of the movie, conductor Lydia Tár is being interviewed onstage by The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik. Her accomplishments as a powerful, lesbian conductor are on full display; she’s an icon. In an important part of the interview, she discusses composer Gustav Mahler’s intent in writing his fifth symphony, which she will be recording live with her Berlin orchestra. This setup may place audiences on the wrong track — prepping the anticipation of her inevitable downfall when the harassment allegations we know are coming emerge. If, at this point, we get locked onto one aspect of Tár’s character (labeling her identity as classical music conductor or lesbian, for example), we fail, in a very meta way, to understand creator Todd Field’s intent, and the nuanced discussion underneath.

One of the most tense and talked-about scenes occurs in the first half hour of the film. Tár is teaching a conducting masterclass at the Juilliard School of Music and encounters “BIPOC, pangender” student Max who refuses to play Bach (and other “white, male, cis composers”) because he can’t relate to them, a conversation at the forefront of classical music today. With shocking verbal and physical aggression, even stopping Max’s constant leg jitter with her hand, Tár makes her case for why musicians cannot refuse to play or conduct Bach’s music; if they simplify Bach to his identity, they miss his intent. If you use this one-take scene as a stencil to read the rest of the film, you can follow all the clues that Todd Field presents to make his ultimate point. The scene’s simultaneously diegetic and meta dialogue describes the film itself and the pitfalls by which the audience may misinterpret it. However, it does show that Lydia Tár believes her core identity and intent are artistic, that she and her music-making are more than “u-haul lesbian;” as the film progresses, we see that her core identity might actually be what Max calls her before he leaves the class. Yes, the outward identity Tár has cultivated is separate from and indeed antithetical to her actual intent — her intent is not artistic majesty, as she would have us believe, but purely aggression. In this way, the movie is primarily about how people can be blinded by identity labels, leading to misinterpretation of (artistic) intent, communication, and content.

LISTEN

Oratnitza — Folktron (2015)

As Elisa & I watched the “source material” theme develop in this issue, I figured the time had come to welcome one of my truest musical loves into the Collective fold — Bulgarian folk fusion band Oratnitza. Their music offers a fascinating example of the thoughtful use of source in art/music-making, and (bonus) every one of their songs is a jam.

Oratnitza describes their music as “ethnobass” — essentially, Bulgarian folk music in the context of contemporary bass genres (dubstep, hip-hop, etc.), plus didgeridoo and cajon. Signifying ritual fire-cleansing performed before Shrovetide (the first Sunday before Lent), the group’s name tethers them to associations with traditional Bulgarian life pre- socialist collectivization of agriculture and urbanization; their mission to “regenerate their musical roots into the future” resonates with other cultural tendencies in Bulgaria today. While their discography is chock full of innovative uses of folk source material (naturally), their 2015 album “Folktron” stands out to me for two key reasons:

ONE — the album’s concept is essentially about folk material as such. The artwork integrates design motifs from the heritages represented instrumentally in the group (Bulgarian, Aboriginal, and Peruvian), emphasizing the bringing together of various roots from the visual get-go. In describing the meaning of “folktron,” the group is incredibly explicit about their commitment to folk materials as a basis for their music-making, spinning the idea out beyond technical/musical stylistic fusion to something more philosophical, scientific, even cosmological:

A folktron is an elementary particle, similar to an electron. It is characterized by the low frequency waves it generates, imperceptible by the human ear. This folktronica infrasound is considered prehistoric. Influenced by its subsensory vibration, mankind has made a multitude of attempts to explain and reproduce this early phenomenon by the means of acoustic instruments. The genesis of folk music is actually the result of the particle’s effect on the human ear. The combination of traditional instruments from different continents and cultures allows one to decode the folktron’s most extensive wave spectra. The quantum ethno project you are holding in your hands, presents you the sound of folktron in its rawest possible form.

Oratnitza’s folktron idea posits both a quasi-utopic folk-futurism and a kind of primordial cosmology that takes “folk” as the root of many things and implicates it across all of time and space (presumably beyond or before borders, and not even necessarily Bulgarian in origin — simply accessed by these Bulgarian music-makers). They call it “musical metaphysics.” At the very least, in a practical sense, the music demonstrates one way in which local heritage is rendered legible for modern Bulgarians, and Bulgarian culture made accessible to international audiences — in which music reflects and informs local ontologies of sound while shaping the way living lineages are understood in a globalized context. Even beyond the Bulgarian scene, music like Oratnitza’s can prompt reflection on (and even offer strategies, or at least materials, for coping with) the layering of past, present, and future in our lives, and the way we take on global, cosmopolitan citizenships.

Okay, TWO (and here’s where the “listen” really comes in) — track four, “Zhelkya,” is total source-based brilliance.

Musically, its virtuosic adapting of traditional Bulgarian vocal style and song structure into a “bass” aesthetic context is wicked fun. Lyrically, I absolutely cannot get enough of the lengthy rap about a turtle and a hedgehog going to court in the country’s capital (the quippy English-language track summary provided in the liner notes reads: “A moral lesson on why a hedgehog should never kiss a turtle and on what you reap is what you sow”). In another sense, the song also speaks to how traditional instruments and musicians function as tellers of “unforgettable stories,” a process in which the kaval (traditional end-blown Balkan shepherd’s flute) takes center stage (yes, I’m biased).

In short, Oratnitza handles materials wisely and well, making fun from cultural and temporal complexity and reinforcing that a critical relationship with the living past is a critical part of living here-and-now, and beyond.

This Corner’s title comes from a poem by T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which is initially quoted in Rare Stuff preceding the first excerpt of Aaron’s novel and then again in character dialogue — sources on sources, visions and revisions. For space, we won’t include the poem here, but we do hope you’ll check it out alongside all the other articles in this issue, linked below.

Thank you for joining us for Winter 2023 at The Collective, and we’ll see you in the Spring!

Articles in the Winter 2023 issue:

- Featured Article: Bridges Playing with the past: “Momata Barbi” and Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter as two folkloric futures by Sarah Craycraft

- Ethics Passing the mic from white middle-aged spiritual liberation to post-college travel utopia by Putu Tangkas Adi Hiranmayena and Elizabeth McLean Macy

- Learning Finding environmentalism: A classical musician’s search in nature, the arts, and beyond by Mona Yamazaki Sangesland

- Movement Hey Black Child: A (black femme) look at imposter syndrome by Tori Tyler

- Performing The musicologist musicks: A quest for expansive expression in a male-coded discipline by Kathleen McGowan

- Politics “It already has”: Speed Racer and impossible hope by Ian Nutting

- Nugget Winter 2023: Media Mélange by Contributing Writers